May 2015, Vol 242, No. 5

Features

Uncertain Prospects for Indias Pipeline Ambitions

India, the second-most populous country in the world and fourth-largest energy consumer after China, the United States and Russia, is home to abundant supplies of coal, oil and natural gas.

Nevertheless, according to the International Energy Administration, India’s per capita energy consumption remains about one-third of the global average as it becomes increasingly dependent on energy imports to support average annual economic growth of about 8%, population increase and rapid urbanization.

With the Indian economy set to exceed that of Japan and Germany combined in 2019, according to IMF figures, the nation badly needs to increase its energy supplies and address its chronic infrastructure deficit.

The current five-year plan proposes expanding the domestic gas pipeline network to 18,000 miles by 2017, from 9,200 miles in 2013. In July 2014, India’s new Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced plans to construct 15,000 miles of gas pipelines over the next decade.

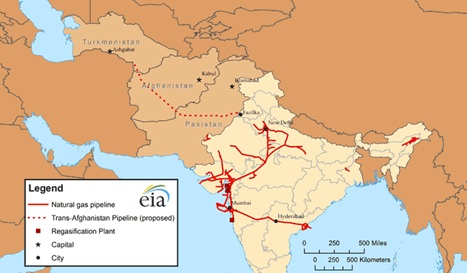

India’s existing gas pipeline network is severely limited in its geographic reach (Figure). The main gas pipeline network leaves Mumbai, transmitting gas originating from offshore to New Delhi in the northwest. A cross-county branch pipeline brings gas from the offshore Krishna-Godavari gas producing fields of the east coast to Mumbai. The current design capacity of the natural gas pipeline system is about 334 million metric standard cubic meters per day (scm/d).

Two pipeline companies dominate long-distance gas distribution in the northwest. State-owned GAIL (India) Ltd operates the Hazira-Vijaipur-Jagadishpur (HVJ) line running from Gujarat to Delhi as well as the Dahej-Vijaipur (DVPL) pipeline.

With a combined length of 3,328 miles, GAIL operates about 70% of the country’s entire gas pipeline network. In 2009, private sector company, Reliance Gas Transportation Infrastructure (RGTIL) completed its 881-mile East-West pipeline, linking the 20 Tcf Krishna-Godavari (KG-D6) offshore gas field to GAIL’s pipeline network and demand centers in the northern and western regions. Regional markets in northeastern India and Gujarat are supplied by the Assam Gas Company and Gujarat State Petronet Limited (GSPL), respectively.

What’s Driving Demand?

Demand for gas, especially from the power sector, fertilizer producers and rising population is expected to more than double to 516.97 MMscm/d by 2021-22. Similarly, domestic gas production is forecast to increase from 100,000 scm/d in 2013 to 163,000 scm/d in 2018, reaching 230,000 scm/d in 2030, according to the government-commissioned report Vision 2030.

India was self-sufficient in gas until 2004 when it began importing LNG from Qatar. Today, India is the fourth-largest LNG importer and Qatar remains the main supplier to India’s four west coast import regasification terminals. LNG imports are projected to rise from 44.6 MMscm/d in 2012-13 to 214 MMscm/d in 2030.

To help satisfy rising demand for gas, India’s chronic infrastructure deficit has attracted government attention. In October 2014, Modi’s new government increased natural gas prices by 34% to encourage investment in increasing output, new pipelines and additional import terminals for rising LNG imports.

Furthermore, to help meet India’s Kyoto obligations, the government is encouraging a switch from coal to gas in power generation with the use of “Dutch auctions,” according to Economic Times.

GAIL plans to increase its network and integrate southern India with its pipeline network in the northwest. In early 2013, GAIL commissioned the 600-mile Dabhol to Bengalur (Bangalore) pipeline, the first line to connect the southern part of India to the national grid.

Increasing LNG imports as well as adding new import terminals will also generate new pipelines in the future. For example, the newly commissioned LNG regasification terminal at Kochi will require a pipeline to Mangalore and other parts of southern India.

However, while government-regulated low gas prices, state regulations and land rights are ever-present obstacles to new domestic pipeline routes, long-held dreams of pipeline connections to gas producers in the Middle East, Central and Southeast Asia face other difficulties.

Proposed in the mid-1950s, the 2,700-km Peace pipeline is planned to link Iran’s super-giant 51 Tcm offshore South Pars Gas field with India via Pakistan, with the Iran-Pakistan section of the pipeline possibly completed in 2016 or 2017.

First introduced in the 1990s, the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) gas pipeline is a 1,814-km project which is expected to cost $10 billion, according to the Asian Development Bank. If built it would supply 38 MMscm/d of gas to India. It appears close to a final decision from the four participating nations. Nevertheless, doubts remain about building in Taliban-infested Afghanistan and terror-infested Pakistan.

More likely than the TAPI project is the plan to construct a deep-sea gas pipeline giving India access to Iranian gas. Serious negotiations over the plan to construct an Oman-India Deep Sea pipeline, crossing the Arabian Sea and linking India’s gas network with Oman’s, thereby bypassing Pakistan, are underway.

The 900-km Myanmar-Bangladesh-India pipeline project was first proposed in 1997 to deliver 5 Bcm of gas from the Sittwe offshore field in southern Myanmar to power plants in Dacca, West Bengal, via Bangladesh (Figure 3).

Of these four proposals, the Myanmar-Bangladesh-India pipeline is the closest to getting the go-ahead and has support from both Dacca and Delhi.

Conclusion

Politics, land rights and insufficient incentives under government-regulated gas prices bedevil exploration and development of domestic gas fields as well as construction of new gas pipelines. In these circumstances, it is seemingly easier, albeit more expensive, to import natural gas by LNG tanker to regasification plants located at ports close to markets than to overcome the many obstacles to building pipelines throughout India.

Comments