January 2015, Vol. 242, No. 1

Features

Kinder Morgan Abandons The MLP, Williams Embraces It

The master limited partnership structure has been popular for pipeline companies for many years, and the shale boom has only intensified its usage—of the roughly 120 MLPs operating today, over 60 percent are less than five years old. But as the industry has adjusted to unconventional production and operations and construction activity assume a new normal, energy companies’ financial moves are becoming big news.

Mergers and acquisitions are up—PricewaterhouseCoopers reports that third-quarter 2014 M&A activity in the U.S. oil and gas industry was the highest in a decade. Meanwhile, several large pipeline companies have made dramatic moves in seemingly disparate directions. Williams announced in late October that it will double down on the MLP structure, combining its Access Midstream and Williams Partners partnerships into one MLP in a $50 billion deal. Meanwhile, in November, MLP pioneer Kinder Morgan finalized the transaction to absorb its three partnerships into its general partner in a $71 billion merger.

What’s driving these changes? What do they indicate for other pipeline companies—are we witnessing the beginning of a trend? And what are the implications for pipeline construction, smaller operators, investors, and support companies?

Growth By Any Name

First, the good news: midstream sector investment experts continue to expect strong expansion and plenty of interest from the market. Whatever organizational structure is put to use to finance and manage construction and operations, building new infrastructure is key to midstream firms’ growth, and growth is what investors demand.

When it comes to infrastructure needs, “I think the opportunity today is as large as it’s ever been,” said Scott Archer, managing director of Tudor, Pickering, Holt & Co. “Obviously the shale revolution has driven that, but there’s literally tens or hundreds of billions of capital that need to be invested over the next decade-plus.” When those with capital to spend are forming a new business or making decisions about where to invest, they “look for where the best opportunities are, and there is a tremendous need for infrastructure. There are a lot of private capital providers and companies that are looking at ways to execute a broader midstream strategy.”

Money that might otherwise go to other industries is flowing steadily into pipeline and other energy infrastructure expansion, fueling the growth that keeps the sector busy. Part of the reason for that is the fact that the MLP structure provides not just appreciation growth of an investment but regular, predictable income from quarterly distributions. In the current financial environment, that sets the sector apart.

“I think the fact that there are not a lot of great yielding investments right now certainly benefits MLPs, along with some other sectors that also provide yield,” Archer said, naming REITs and utilities in particular.

“For a lot of companies [the MLP structure has] provided an additional funding source for midstream investment or infrastructure investment,” Archer said.

This ready cash has helped speed up and expand the infrastructure building spree North America has engaged in over the past few years. Without the MLP structure, we might well expect fewer pipelines under construction and newly in the ground.

According to Archer, many MLPs have been able to access capital to fund new ventures at a lower cost than other similarly sized companies. “As the MLPs are valued on yields, their valuations in general—not in every case, but in general—have tended to be higher than a similar set of assets held within a C-corporation structure,” he said. The advantage is not solely based on the current low-income marketplace, either. “Even if other investments start providing some yield opportunities, MLPs will probably still be unique in that they will be providing both yield as well as some growth. That combined total return has been very attractive to investors and I suspect will continue to be.”

Victims Of Success

However, the same quirks of organization that recommend the structure can mean that an MLP itself can’t effectively pursue long-term or cost-intensive projects, and there are circumstances in which the MLP’s methods of raising money become less efficient rather than more. These potential stumbling blocks are inherent in the structure and the marketplace, rather than something a good management team can control for, and therefore a pipeline company organized as an MLP may need to move through “life cycle” structural changes to accommodate the changing requirements of its structure and investors.

The better the MLP performs, the larger the share of its income goes to the general partner, despite the fact that most general partners own approximately 2% of the units in the MLP. Limited partners, the investors, receive a set amount based on the MLP’s cash flow. When the MLP wants to embark on a new project, it sells new units (shares) in the partnership to the stock market.

[Sidebar: How MLPs Work]

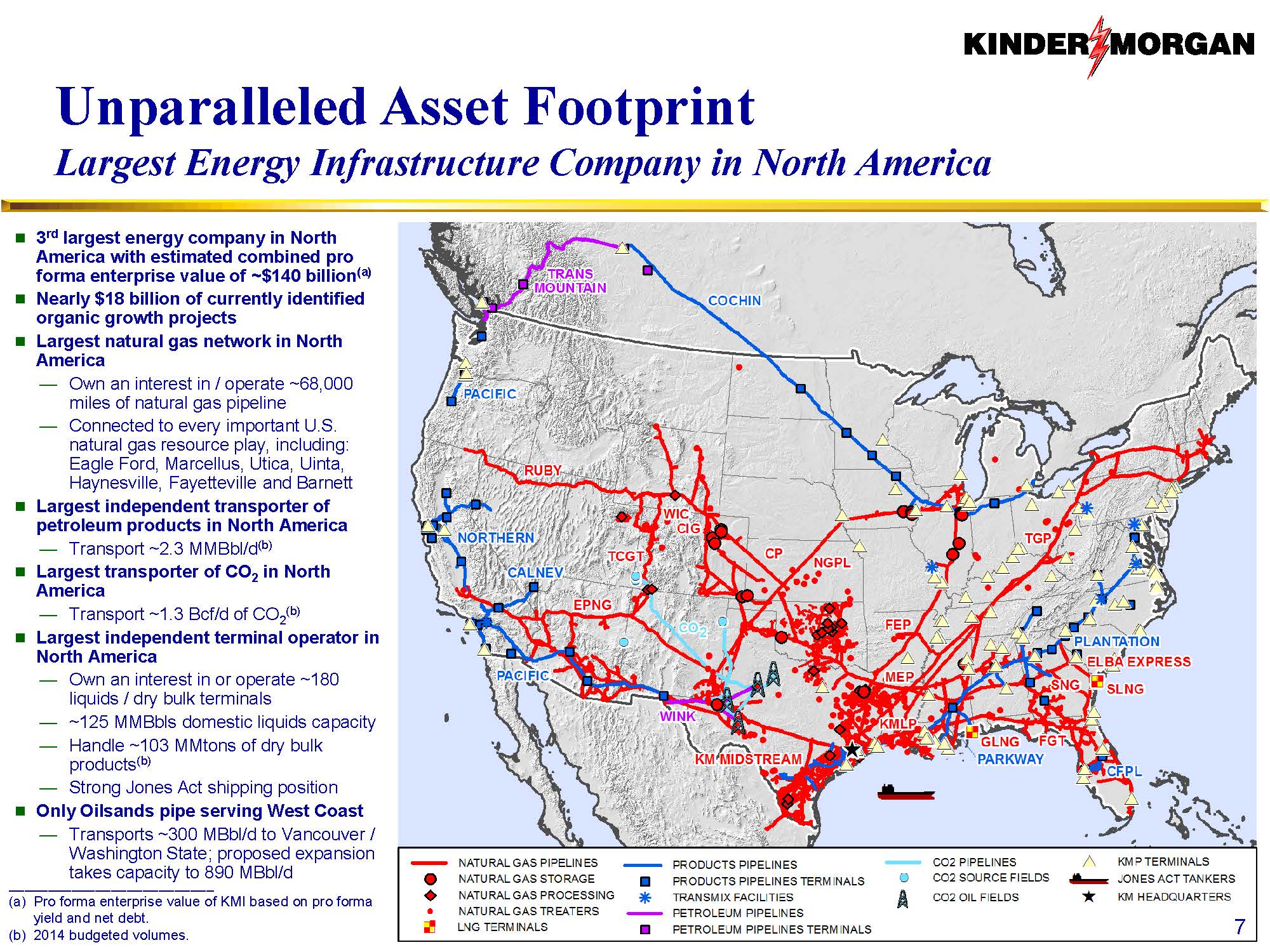

One way the structure can be reinvigorated is to consolidate the number of partners in the priority line. Williams’ move to combine its Williams Partners and Access Midstream businesses into a single MLP is one example. “The MLP structure is important to Williams fulfilling its role as a premier provider of large-scale infrastructure that connects the growing supply of North American natural gas and natural gas products to growing demand for clean fuels and feedstocks,” said Tom Droege, spokesman for the company. The move is the latest in a series of deals for the company, including the acquisition of Access Midstream in June and the closing of a merger between Williams Partners LP and Williams Pipeline Partners LP in August. “Energy infrastructure is largely a fee-based business, which creates stable cash flow to the MLP and, in turn, stable and growing cash distributions to the unitholders of the MLP. These cash distributions are tax efficient because no tax is incurred at the partnership level and deductions such as accelerated depreciation are passed on to the unitholders. This low-risk, tax-efficient business model allows Williams to raise capital at a low cost and therefore makes Williams investment opportunities more attractive,” said Droege. “It’s a step in the right direction for the Williams family,” said Jason Stevens, director of energy equity research at Morningstar. With Access Midstream as the surviving entity, the new organization will pay Williams its favored distributions at the lower Access level, rather than the higher Williams Partners level. When a well-performing MLP begins to pass along too much of its cash to the general partner, it’s hard to avoid problems developing with investors, Stevens said. “For almost all MLPs that have a general partner that holds incentive distribution rights, at some point the general partner’s share of cash distributions create such a headwind on distribution growth to limited partners that it becomes challenging to grow at peer averages without putting up massive amounts of total cash flow growth each year.” When the company doesn’t grow at the same rate as its competitors, investors are likely to get restless. That can make the valuation of the company suffer, or it can dampen interest in the additional units sold to raise capital for new ventures. A lowered response means new capital is more expensive to the organization, and therefore new ventures cost more to undertake. High capital costs may then depress growth potential, just as growth becomes even more necessary from a business standpoint. One or an interlinked constellation of these factors can make life difficult for an MLP’s management, and often a structure change of some kind is the solution. Kinder Morgan also suffered from wounds brought on by too-high incentive distribution rights, especially at Kinder Morgan Partners. “We’ve been a victim of our own success, to some degree,” said Kinder Morgan Vice President and Chief Tax Officer Jordan Mintz, speaking to a conference. “Those IDRs pull away so much cash, almost 50% of the cash generated by KMP, that it’s really tough to find those type of investments that give the kind of return you want to give to unitholders.” While raising capital had never proved problematic, the level of year-over-year cash flow growth needed to remain competitive was becoming prohibitive. “In Kinder Morgan’s case it’s struggled with this for years,” Stevens said. “They bought El Paso and that gave them another three or four years’ lease on life as a growing entity as they played through the drop-down story,” said Stevens. “As that began to filter through, if you’re [CEO] Rich Kinder, you’re looking at the market saying, where am I going to drive another $3 to $4 billion year of capex at an attractive multiple, when competitors can chase the same projects that I want at a lower cash cost of equity?” As a C corporation, KMI has no restraints on its choices of where to distribute income, and can also reinvest its gains directly in new projects without going to the market for new money if it chooses. It can assuage investors’ need for yields with planned dividends. It will be able to claim depreciation deductions on capital expenditures, sheltering income that previously flowed from El Paso and KMP as fully taxable. And the consolidated mega-company may benefit from its dominant size in terms of merger and acquisition opportunities. Meanwhile, day-to-day activities at the lower levels may change very little. Asked how the move away from MLPs might affect construction and operations, Larry Pierce, spokesman for Kinder Morgan, said, “It will not affect the way we do business. It just puts everything under one roof, which simplifies the Kinder Morgan story for investors and gives us access to a lower cost of capital to spearhead growth.” Choosing A Path “The fundamental difference is that MLPs have to raise all of their growth capital externally, through borrowing, debt offerings or equity offerings,” Archer said. For young companies that might be an advantage, but for sufficiently large organizations the difference can be more than made up with the freedom from required distribution levels and timing. As for the tax benefits to the MLP versus the C corporation, Stevens said, they might be a more potent deterrent at another time. “There are no structural impediments to either of them at the current moment. Particularly with the [November 2014] election results, I don’t think you’re going to see a rush to tax MLPs as corporations. Corporations do have to deal with double taxation—effectively the entity-level cost of capital is slightly higher than for the average MLP.” But the tax barrier for C corporations in the energy industry is not usually a significant expense, he said. “You’re talking about a space that puts a lot of capital to work, so your depreciations shield in any given one year is pretty significant. Your actual effective tax burden is quite low. It’s not zero like an MLP, but it remains competitive,” said Stevens. Bigger And Better? Larger size gives a company advantages, said Stevens. “For two reasons: first, the more interconnected your asset footprint is, the more opportunity there is for either infill projects or large new ventures that cut across the white space on the map. Second, the larger your firm, the more natural of a consolidator you are. So your Kinder Morgans, Enterprise Products, Williams and Energy Transfer Partners of the world are in the catbird seat to look at possible acquisitions to see what makes sense for their specific systems.” In a release on the company’s website, CEO Rich Kinder said the new Kinder Morgan plans to pursue growth via acquisition in “a very fertile space.” The new organization has a projected enterprise value of $140 billion; Kinder’s presentation cited 120 total U.S. energy MLPs with $900 billion in enterprise value. Enterprise Products Partners LP is estimated at an $88 billion enterprise value, and Energy Transfer Partners is at $40 billion, while on the non-MLP side Enbridge Inc. is at $66 billion and TransCanada at $62 billion. Guy Buckley, chief development officer of Spectra Energy, with an enterprise value around $40 billion, references the company’s large footprint as a sign of reliability in an uncertain construction cycle. Producers considering open seasons have more to worry about than the route and cost of a pipeline. “People are coming to us because they want to know, if I sign up, is it going to get built, is it going to get executed?” he said. “I think that’s going to provide the key difference going forward in how infrastructure gets built out.” Most MLPs are still smaller companies, operating far below this massive scale. But “smaller” is relative. At Deloitte’s energy conference in November, DCP Midstream CFO Sean O’Brien cited an average market capitalization of $4 billion dollars across the MLP sector. (DCP Midstream Partners, the MLP, has a $4.72 billion market cap and $7.18 billion enterprise value.) O’Brien noted a trend toward expansion across the value chain, from fractionation and NGL transport to export options. “The big companies, consolidating companies now, including ours, believe you have to play across this chain.” He named benefits including savings from economies of scale and greater purchasing power, greater diversification and risk mitigation, but O’Brien said the primary rationale behind DCP’s move toward vertical integration is to “control our own destiny.” Integration protects against repetition of past difficulties getting products to end markets, O’Brien said, and also offers a simple solution to customers. “A lot of our producers come to us and say, we want you to take our product from the wellhead and get it all the way to the clearing centers. If we can do that, we believe that’s a competitive advantage.” Not every corporate move in the pipeline industry through the next years will be in the tens of billions and above. But with a growing pool of increasingly large players, more headlines on financial shakeups, takeovers and reorganizations are sure to come. Ambitious infrastructure companies remain a magnet for investor dollars, cushioned as they are from direct impact from low oil and gas prices and an uncertain economic outlook. Meanwhile, demand for new pipe is far from sated. With cash to hand and plenty of projects, the pipeline sector may be poised to find out exactly how big its businesses can get. MLPs are unequal partnerships, composed of a general partner with a small number of units, often 2% of the total, and limited partners who hold the rest. Limited partners are only investors and do not have management powers. The general partner controls the MLP and is paid on a sliding scale for its efforts—the more cash the MLP brings in, the larger the percentage of the income that goes to the general partner. The general partner’s opportunity to earn disproportionate returns is known as its incentive distribution rights, and pay schedules and rates are determined ahead of time. The MLP structure is also only available to businesses in certain industries, and because of the business sector restrictions and the requirement for quarterly distributions, the vast majority of MLPs are at least in some part pipeline companies. Pipelines produce the stable, positive cash flow that fuels distributions, creating yield. Many pipeline companies can also expand quickly, which increases the value of units in the partnership, creating growth. Expansions are often accomplished by buying ready-to-go assets from the general partner, which is called a drop-down. This maneuver allows the MLP to grow without a long wait and tricky expenses to fund construction, and it allows the GP to get cash for the value of its assets while continuing to receive income from them as well in the form of distributions from the MLP. Mergers and acquisitions are another source of quick growth. Shale development has led some contractors to build gathering systems and local pipelines for quick sale to larger entities, and MLPs are often buyers for these systems. As the MLP gets larger and earns more income, the split of cash determined when it was started begins to substantially favor the GP. When those holding 2% or so of the company’s units begin to collect 15% or 20% of its cash flow, LP investors can become less content with the arrangement. This is usually the trigger for a reorganization of the entity. The reorganization can bring in more surprises, though. One side effect from KMP’s switch to a C-corp is that some investors will now owe considerable taxes. Taxes on yields distributed to partners in an MLP are often deferred, because the income is considered to be partial payback for the initial investment in the partnership. Once the full amount invested is paid back, taxes can still be put off if the unitholder does not sell his or her piece of the company, because gains have not been realized yet. But if the units are sold, the proceeds are taxed not as capital gains but as income, which for most investors will mean a higher amount due to the IRS. Because the Kinder Morgan unification is designed as a sale of the partnerships to the C corporation, in many cases deferred taxes incurred since the partnerships went into business will now come due. Kinder Morgan was taken somewhat by surprise at the investor outcry resulting from that transaction being taxable, said Jordan Mintz, chief tax officer for the organization. But he also suggested that there has been some “disingenuity” in the portrayal of investors’ plans to hold the units until death and pass them to their heirs (which would wipe out any associated tax burden). In ten years of tax law practice, he said, “Every time I told my clients that the tax plan was that they die, they never returned my phone call.”

“A pipeline operating in a C corporation is going to operate the same way as a pipeline operated in an MLP,” said Archer, “the difference being that as that pipeline distributes cash flows, one set of cash flows is distributed out to the partners in the MLP format, whereas in a C corporation earnings and profits could be reinvested or they could be distributed out or used for other purposes as well.

Although there may be little to choose between one financial structure and the next aside from each company’s individual circumstances and needs, the results of transactional moves do point to a trend: bigger organizations. The pipeline sector is now home to several very large businesses, and both the Kinder Morgan and Williams deals will produce $50-billion-plus integrated mega-companies with assets spread across the continent.

How MLPs Work

A master limited partnership is essentially the same as a limited liability corporation, or LLC, traded on a public exchange. It must pay out its excess cash flow to its investing partners on a quarterly basis, and cannot hold funds for reinvestment. This allows MLPs to avoid paying corporate income tax, passing the tax burden on to the partners. However, it also requires that the MLP only get funds from offering new units. New units must be sold at a price that will compensate the existing partners for the decreased percentage of the company they will now own.

[Return to main text]

Comments