May 2014, Vol. 241, No. 5

Features

IEA Economist: Shale Gale Will Result In 20 Years of U.S. Dominance

IEA Chief Economist Fatih Birol synthesized the agency’s 2013 World Energy Outlook and his own analysis to suggest that for the next 20 years, low energy costs caused by the early and plentiful development of shale gas and energy infrastructure will give the United States a large competitive advantage over other nations when it comes to attracting and developing business.

“For many years to come, both in the natural gas and electricity prices, there will be a substantial cost differential between the United States and many of its economic competitors,” Birol said. For the United States, he said the question to consider was “How much can I do in the next 20 years to make the most out of this time frame?”

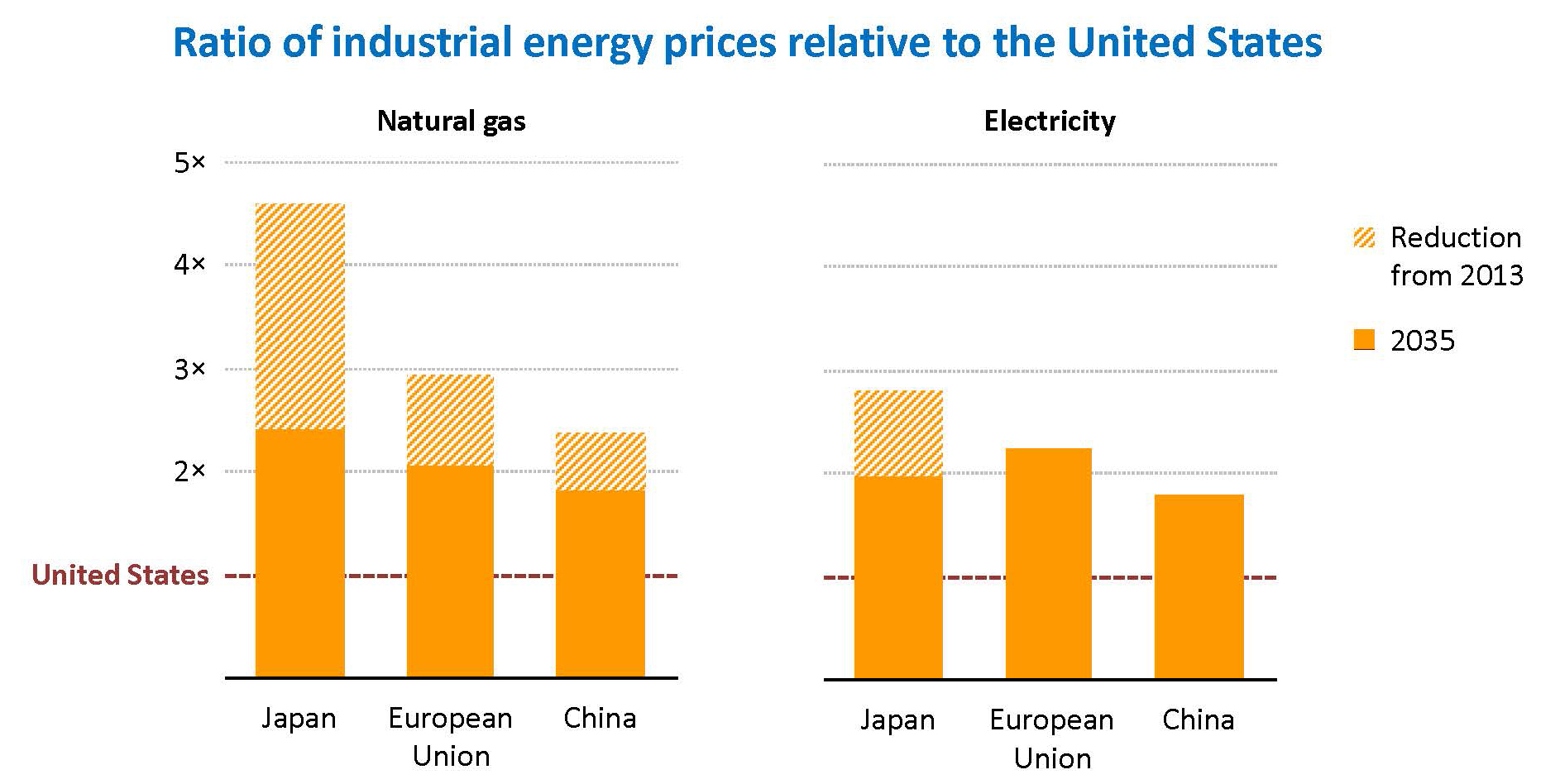

The sudden shift in opportunity comes from an uneven shift in prices. Significant regional differences in price for the formerly global commodity are now expected to continue for decades at least. “Today [natural] gas prices in Europe are three times higher than in the United States and five times higher in Asia in general. I do not know any other important commodity valued at such major price differentials,” said Birol, speaking at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy Feb. 20. “This is very bad news for Europe and Japan but very good news for the United States.”

The twin sources of the U.S. advantage are the development of shale resources and the large and efficient network of transportation infrastructure already in place. While the distribution of shale oil and gas within the U.S. is a prerequisite to its fortunate position, deposits of similar value exist worldwide. However, in addition to being first on the scene with the technology, geological information and social license to develop its local resources, the U.S. is uniquely possessed of the infrastructure to move energy to market.

“This is a structural issue. We believe this price differential may narrow down a bit, but will be with us for many years to come,” Birol said. “European gas prices will be in the next 20 years at least two times more expensive than U.S. gas prices.” Japan’s rates over the period were predicted at about three times higher than the U.S. “In terms of the electricity prices we also see a similar trend.”

Asked whether the Obama administration agreed that the U.S. had such an advantage over the next two decades, Secretary of Energy Ernest Moniz avoided quantitative statements but agreed on the general terms.

“We obviously have a substantial competitive advantage today and we expect that to be sustained for some time. Twenty years, 10 years, 15 years, who knows,” he said. “Our advantage lies not only with the rocks but with the infrastructure that we have. Even though we still have challenges, we have an unparalleled infrastructure.”

Moniz clarified that in addition to physical infrastructure, he considered the market mechanisms at use in the U.S. a component of the advantage. “We are by far the location in the world that best aligns supply and demand.

“We see a substantial advantage in the U.S. It comes from the geography, the market structure, the infrastructure, and we want to see that developed. The president said in the State of the Union that he estimated close to $100 billion had been invested in new manufacturing capacity because of the low to moderate gas prices,” Moniz said. “I think that was a good statement. It may even have been a bit on the conservative side.”

The better infrastructure situation is the obvious advantage for the U.S. over Canada and Mexico. All of North America is expected to see benefits, but not on the same scale.

The lower electricity prices driven by abundant resources and efficient transportation double the effect against Europe and Japan, where Birol said energy-intensive industries contribute 30% of the economic output. He defined these as businesses, including petrochemical manufacturing and aluminum, iron, steel, pulp and paper mills that have three main cost centers: labor, capital, and energy. Long-term lower energy costs and competitive capital and labor costs in the U.S. were therefore likely to lure many companies away from disadvantaged countries.

“This can give a very strong boost to the U.S. economy,” said Birol. “It wouldn’t be a surprise if we see around 2015 or 2016 a very strong comeback of the U.S. economy as a result of what is occurring in the manufacturing industry, but also on the balance of trade.”

Ben Bernanke, former chair of the Federal Reserve, noted the contribution the change in energy sources has already made toward rebooting the American economy after 2008 when he spoke to the IHS CERAWeek conference in March, the same event at which Moniz took questions. “The U.S. had a very big trade imbalance, a trade deficit, about 6% of GDP prior to the crisis. It’s now closer to 2-3%. Some of that is just structural change and other factors, but clearly the reduced reliance on foreign energy has had a positive effect on our trade imbalance.”

Transportation Is Key

“Moving gas long distances, no matter how you do it, adds very substantially to the cost. So from that point of view we clearly have natural advantages that are going to be sustained for some time,” Moniz said.

Birol said that in Europe and Asia he often hears audiences suggest that American gas simply be exported overseas to create a single commodity price, as is mostly the case for oil. However, he explained, transportation costs over sea are seven times higher for gas than the equivalent amount of oil, and make it impossible for Europe to see the same gas prices from imports. Transportation costs mean that gas selling at $4/Mcf in the U.S. would cost $11/Mcf in Europe, Birol said, with Asian prices another step higher.

“It’s a life and death problem. There is no one single speech of a European leader which does not address the problem of competitiveness,” Birol said. Regional price differences will remain and cause gaps in competitiveness for years to come, he said, although he expects to see shale developments in other countries soon.

Wider shale development will not immediately change matters, even in China where there have already been several steps toward implementing the technology. “If China should develop their shale gas very effectively, assuming it is there to be developed effectively, they have a large resource, but the economics of it still remain to be demonstrated,” Moniz said. “They would also have a situation of a very substantially increasing demand and a supply that’s essentially contiguous.”

While developed countries should expect little in the way of demand growth, the sources of energy outside North America are creating additional tensions of their own. Europe was becoming wary of its energy dependency on Russia even before the latest incident in Crimea. The renewable energy technology expected to become part of the energy mix has also grown controversial.

“In Europe, many countries, Germany, Spain, Italy, are cutting renewable subsidies” as governments have to make choices on where to spend diminished funds. Without subsidies, renewables can’t produce enough energy to pay for themselves as of yet, and without investment, are unlikely to improve, Birol said.

Increased efficiency is Europe’s best chance to chase low U.S. energy costs, he said, while the nuclear energy that has fallen by the wayside after the Fukushima disaster is Japan’s best option. It might prove important to Europe as well.

Birol also lauded the stabilizing aspect of diverse sources of energy as opposed to worldwide dependence on a few energy-producing countries. But he warned that the upswing in North American production does not wipe out the importance of energy resources elsewhere. “It is very important to understand and make others understand that the Middle East is and will remain crucial for the global oil markets for many years to come,” he reminded the audience, and continued investment in its conventional reserves will be necessary to feed rising demand.

Neither should the U.S. lose sight of the temporary nature of its advantage. After the end of the 2020s, according to the EIA’s projections, production levels for U.S. shale oil will drop off. Transportation and gas production advantages will eventually equalize and the world can expect new trade relationships at play.

Carbon Costs

Of particular concern to Birol is the future of energy efficiency, renewables, and climate-friendly actions in the current economic context. While the consensus on climate change grows, readily available sources of fossil fuels have been discovered in abundance ready and able to fuel a surge of development in poor countries.

In China, India, and the rest of Asia, where the biggest projected increase in power demand comes from, most energy comes from fossil fuels, with no change projected in the near future. One-third of the projected increase in world demand for oil from 2012-2035 comes from Asian trucks alone.

The increased population and pace of development will take its toll. EIA forecasts that although the vast majority of carbon emissions to date have come from OECD countries, if the years 1900-2035 are considered as a bloc, the developing countries will have contributed almost half the total emissions.

Meanwhile, governments in Europe are backing away from renewables as they find their energy costs up and their competitiveness down. As gas use too is down in Europe, coal has taken up some of the slack, notably in the Germany and the United Kingdom, which is burning more coal than it has since the end of World War II.

One way out of the bind Birol sees is a renewed emphasis on carbon capture and storage technology, a “critical technology” little discussed in recent years. “If this technology becomes mature and economically and politically accepted, we have huge fossil fuel reserves which could … increase the wealth of the global economy. This is something I would like to see.” He noted that 1.3 billion people worldwide still lack electricity.

The ability to deploy the economic power of fossil fuels without paying the price in carbon emissions would be a true game-changer. “But I am realistic,” he said. “I don’t see this happening very soon unless there is a significant government and industry push.”

Comments