Non-Invasive Flowmeters Measure Natural Gas Flow and Composition Without Process Penetrations

By F. JOUBERT, Emerson, Lyon, France; and E. SCHWEDE, Emerson, Berlin, Germany

(P&GJ) — Looking back a decade or two, natural gas came from traditional fields with predictable composition and characteristics. As natural gas began to replace coal, demand increased, causing producers to develop new fields and drilling techniques, especially fracking, expanding the range of sources enormously, while also reducing composition consistency.

Today, with liquified natural gas (LNG), hydrogen (H2) blending, biomethane blending and other new sources, the range of supply is wider than ever. Consequently, the chemical composition of natural gas can vary widely, changing its characteristics for fuel use on a daily basis. Therefore, gas producers, pipeline companies and end users need to constantly monitor its composition to determine makeup, heat value and contaminants at multiple points in the supply chain to ensure they do not experience problems.

Natural gas is nominally methane (CH4), which typically accounts for approximately 80% to 98% of its volume. The balance can be all sorts of products, including heavier hydrocarbons (up to C9+), non-combustible gases, low-heat-value combustible gases and contaminants. Regulatory agencies and pipeline companies globally define natural gas quality by limits on components other than CH4. While there is some variability, most regions include specification ranges for:

- Wobbe Index

- Higher hydrocarbon content, through C9

- BTU value (heat value or calorific value)

- Relative density

- Total sulfur content

- Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) content

- Water (H2O) content

- H2 content

- Carbon dioxide (CO2) content

- Oxygen (O2) content.

Analysis requirements. Required gas analysis depth and detail varies significantly depending on the application, but most variables ultimately reflect thermodynamic properties. Where a component-by-component percentage is necessary, such as a custody transfer point, a gas chromatograph (GC) will be in use. GCs can be slow, costly and maintenance intensive, but today’s models are much better than earlier units, although sampling systems remain particularly troublesome in many applications.

Where the Wobbe Index is critical, such as fueling a gas turbine, a specialized Wobbe meter is often used simply for that calculation. In other situations, a flow computer may calculate critical values based on a density constant, which cannot always respond properly to gas variability.

As a practical matter, the level of analytical detail must match the application. Custody transfer at a major pipeline hand-off point requires the highest accuracy and measurement of the most variables, but there are many situations where standard volume calculations are sufficient. In some instances, it is simply a matter of verifying that the supply meets the basic regulatory definition of commercial natural gas.

The American Gas Association (AGA) provides a method for calculating thermodynamic properties of natural gas by measuring density and compressibility, as these are closely related to its composition. So, how does this work?

Natural gas does not behave as an “ideal gas” because it deviates from what should be ideal characteristics. Since this is well understood, the degree of deviation is expressed as a compressibility factor designated as Z. In this context, an ideal gas has a Z factor of 1. Natural gas, depending on conditions and its composition, can show a Z factor below or above 1, with the exact factor providing direct insight into its chemical makeup. This is not quite as detailed and accurate as readings from a GC, but it is much easier to measure, and it can be done in real time in conjunction with flow measurement.

Measuring the Z factor can indicate the presence of higher hydrocarbons (relative to CH4) capable of increasing British thermal unit (BTU) value, but also likely to liquify in pipelines. It can also indicate non-hydrocarbon impurities, such as nitrogen (N2), CO2 and H2S. A GC can back into a Z factor, calculating it based on composition, but where the specific Z factor is measured directly, it provides a useful proxy for more sophisticated gas analysis. This technique is recognized and included in standards and studies from the AGA, the U.S. National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST), the Pipeline Research Council International and other organizations.

For each application, a range of possible compositions can be defined—for example, the high caloric gas typically transported in pipelines, or more specific targets for critical production areas. Within this range of compositions, measurement techniques are available to measure sound speed, along with pressure and temperature values, to calculate compressibility and molar mass. With known molecular weight of the carrier gas, the percentage of a single impurity can be determined (e.g., H2 in natural gas). With a more precise definition of the application range, correlation uncertainty can be reduced, producing an uncertainty statement for each correlation model.

Measuring molar mass and density can also serve as proxies for more detailed chemical analysis since composition has a direct influence on these values. So, for a natural gas producer, pipeline company or large-volume consumer, how can these be put to work on a practical basis to work in parallel with or supplement custody transfer measurements?

Understanding a dynamic gas master. To put this situation into context, consider that a large-scale natural gas custody transfer point will use a flowmeter—likely a Coriolis mass flowmeter or an eight-path ultrasonic flowmeter—to measure volume (FIG. 1). A GC will work in conjunction with the flowmeter to analyze the composition, thereby determining actual energy value, levels of contaminants and other factors—which can all influence pricing. This kind of setup is very common, but it can be expensive, especially with larger pipe sizes.

A dynamic gas master (DGM) can provide much of the same data, although in different ways, and it is capable of delivering very similar results, but with far less costly equipment and no need for process penetrations. This approach uses an externally mounted ultrasonic flowmeter, clamped to the pipe in any practical location, supplemented by line pressure and temperature measurement. If there is no nearby temperature measurement available, this can also be taken by a separate instrument, through the pipe wall, without a process penetration.

A DGM measures gas flow and composition in real time, providing a standard cubic meter per hour (m3/hr) reading with the molecular weight, and adjusting calculations when gas composition varies (FIG. 2). This provides a working measurement competitive with conventional custody transfer valuations. A DGM does this by measuring gas velocity for flow, and for the sound speed of ultrasonic pulses passing through the gas. With this measurement, combined with pressure and temperature readings, it is possible to perform a range of calculations to determine:

- Z compressibility factor

- m3/hr flow

- Molar mass

- BTU value

- Density, base and operations.

Volumetric flow and molar mass are available as primary variables and can be sent to a host automation or asset management system continuously. The following case studies show how a DGM can be used advantageously in various applications.

CASE STUDIES

Example 1: Applying compressibility monitoring. A major European natural gas transport operator has many locations where it is critical to have an accurate picture of how much gas is passing through strategic points and its composition. When presented with the possibility of using flowmetersa to replace more troublesome measurement methods, company engineers decided the potential advantages were worth exploring.

The company conducted a series of tests to determine if this ultrasonic technology could deliver all the required data (FIG. 3). A double channel DGMb, tuned to 500 kHz, containing pressure and temperature data, would have to measure standard volumetric flow (m3/hr) through a 6-in. pipeline at pressures between 3 bar and 30 bar. Additionally, it would have to indicate the Z factor, BTU value and molar mass, all compared against existing company standards.

- The tests were carried out on 11 days across three months

- The flowmeter calculated the Z factor and molecular mass from sound speed measurements

- The BTU value was calculated accurately, even with the presence of N2 (0.7%) and CO2 (0.3%) in the test gas.

Engineers administering the test were not expecting analytical accuracy identical to the GC since this was not necessary for the anticipated applications. Nonetheless, they observed deviations well below ±1% from a device that requires no process penetration, no sampling system and delivers real-time data. The DGMb was then installed at multiple locations, including these two examples.

Example 2: Underwater pipeline landfall. The company operates an underwater pipe landfall facility, receiving gas from an offshore producer. Operators found it difficult to reconcile volumes coming into the facility with what was being shipped out. Even after accounting for changes due to initial natural gas processing, the values did not match. The conclusion was that measurements at the inlet were inaccurate, calling for reevaluation of the initial metering approach.

The site was using a legacy ultrasonic flowmeter on the 16-in. pipe at the landfall station. Its performance was suspect, but whether the flowmeter was accurate or not, underlying assumptions about the data were incorrect:

- Pressure adjustment calculations assumed operations between 70 bar and 130 bar, but normal operation was typically around 55 bar, causing a 10% to 15% uncertainty.

- Incoming temperatures fluctuated between 30°C and 45°C, but analysis assumed this was stable, adding 5% to 10% of possible uncertainty.

- Z factor compressibility was monitored, but it was being calculated by the site’s GC located farther downstream after the initial gas treatment and after removal of higher hydrocarbons [natural gas liquids (NGLs)], so the measurement did not reflect the incoming stream at all.

- Reducing uncertainty below 5% would require continuous real-time measurement of pressure and temperature with continuous compensation.

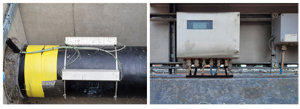

Site engineers installed the DGMb on the incoming pipe with pressure and temperature data inputs (FIG. 4). This solved the problem, producing data able to resolve input and output mass balance.

Example 3: Compressor monitoring station. Large turbine compressors driving gas through pipelines must operate within a narrow turndown range. When their full output is not necessary, some portion is diverted from the compressor output back to the inlet to maintain total volume. Measuring the bypass amount must be very precise for effective control.

Site engineers installed the dual channel DGMb on the bypass pipe, supplemented by available temperature and pressure measurements (FIG. 5). It now measures standard volumetric flow, which has proven suitable for the measurement accuracy required for bypass volume control.

The DGM determines the Z factor by measuring sound speed using the same clamp-on ultrasonic transducers that determine the flowrate. The turbine bypass line is very short and, therefore, does not have long straight sections capable of mitigating turbulence. Using the dual channel configuration compensates for flow profile disturbances in the pipe.

With the DGM’s non-invasive flow measurement, including the simultaneous determination of gas composition and Z factor measurement, compressors are reliably controlled by balancing bypassed gas volume against gas volume fed into the pipeline.

Takeaway. Clamp-on ultrasonic flowmeter technology is not new in concept, but the sophistication of data analysis has grown greatly, providing far more information. Today’s offerings provide deep insights into flow measurement for difficult fluids such as steam, natural gas and compressed air, in addition to more common products.

For natural gas distribution and consumption, clamp-on flowmeters offer unmatched flexibility because they can be installed in any location or piping configuration. When provided with corresponding pressure and temperature measurements, this technology is a very easy and economical method to monitor gas flow and consumption for everything from pipeline branches to individual applications.

As the range of gas supplies continues to grow, the author’s company’s flowmeters can provide information about gas quality at every point of the network, and they can observe new compositional changes, such as H2 concentration from green production sources. Clearly, this technology is well suited to the changing role of natural gas in new energy environments.

NOTES

a Emerson’s FLEXIM Fluxus flowmeters

b Emerson’s Flexim FLUXUS G722 Double Channel DGM

About the Authors

FLORENT JOUBERT is a key account manager at Emerson, where he is responsible for Emerson's non-intrusive clamp-on Flexim flowmeters, specializing in oil and gas industry applications. He has 18 yrs of experience with FLEXIM flowmeters and has held various positions with the company. Joubert earned a dual degree in technical and commercial studies from the University of Annecy.

EIKE SCHWEDE is a global industry management engineer at Emerson, where he is responsible for non-intrusive clamp-on FLEXIM flowmeter as used in the oil and gas industry. He has been working with FLEXIM flowmeters in management, sales and technical roles for more than 12 yrs. Schwede earned a degree in industrial engineering from the Technical University of Hamburg.