GTI’s Hydrogen Technology Center to Research U.S. Clean Energy Distribution

By Maddy McCarty, Digital Editor

Kristine Wiley always knew that she wanted her work to involve science and the environment. Starting as a college intern, GTI gave her the opportunity to do that.

Now, she is helping lead hydrogen research that could contribute to a decarbonized future in the U.S. and determine how existing and future pipelines can help supply reach demand.

For almost 20 years, Wiley has worked for GTI, a research, development and training organization addressing energy and environmental challenges, with her work focusing on natural gas and the environment. Recently, she was named vice president of GTI’s Hydrogen Technology Center, which will facilitate increased use of hydrogen in an integrated energy system to meet the challenges of decarbonization.

“As the transition from environmental focus shifted to looking at low-carbon resources, like renewable natural gas for example, and then hydrogen, my focus area shifted,” Wiley said.

In this role, Wiley will serve as the leader for the center and related business activities, working across GTI to synchronize industry knowledge and technical expertise to serve their customers and stakeholders. While hydrogen research is not new to GTI, the Hydrogen Technology Center will consolidate and streamline those activities.

“GTI has actually been doing hydrogen research since the 1960s, so our first patent was in the mid-1960s. A lot of our work focused around the fuel cell area and transportation,” Wiley said. “Prior to us establishing the Hydrogen Technology Center in 2020, we already had a pretty big portfolio of hydrogen research projects across the full value chain, in addition to developing our own technologies in the hydrogen space.”

Given the momentum and necessity to de-carbonize the economy, there is general acknowledgement that hydrogen will play a role in reducing emissions, she said. A major focus for GTI, in addition to producing clean sources of hydrogen, is leveraging existing natural gas infrastructure, she added.

“There are a lot of emphases and R&D (research and development) investments going into new technologies to produce the many colors of hydrogen,” Wiley said, referring to the categories of hydrogen based on fuel sources, such as green hydrogen from water and blue from natural gas. “Another portion of that is being able to connect that supply with the demand.”

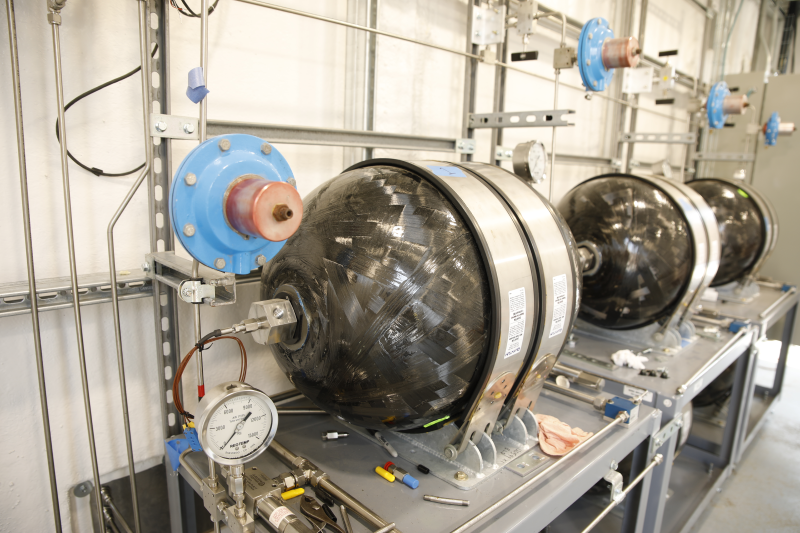

That includes looking at how they can leverage existing pipelines and underground natural gas storage, for example. GTI has assessed blends of natural gas with low amounts of hydrogen, up to 5%.

During a study focused primarily on plastic materials, GTI’s physical testing revealed mixing low amounts of hydrogen with natural gas does not lead to a significant impact to the pipeline system, which is in line with other studies on the topic.

“Now we’re looking at expanding that work. We have a current project that is assessing the impacts of still low blends … but its effect on steel pipelines,” Wiley said.

There is concern about hydrogen embrittlement, so GTI wants to understand what the issues are. They will also look at all the operational parameters associated with natural gas infrastructure, like compliance for leak surveying and detection.

“How are those tools and technologies going to respond now that you have a different blend of gas running through the system?” Wiley said. “So, we have projects and R&D to really look at addressing some of those challenges.”

The consensus is that up to 20% hydrogen blends would not require major modifications to existing pipeline infrastructure, she said. But beyond that, retrofitting or building new infrastructure could be required, so GTI is focused on conducting the specific validation and testing of systems.

“You have to do those site-specific tests, because every system is different,” Wiley said. “Infrastructure is not uniform across the U.S.”

A lot of the studies focused on hydrogen blending have been done in Europe, where infrastructure is different than in the U.S., she noted.

GTI hopes to identify what scenarios, given where an area is geographically located and the supplies it has access to, would allow integration with existing infrastructure and pipelines versus building new pipelines. A similar study in Europe, the European Hydrogen Backbone, found that about 75% of a hydrogen transportation network would utilize existing natural gas infrastructure.

Hydrogen research like this should eventually lead to more job opportunities and cleaner air, Wiley said. A couple of examples would be working with retrofitting existing pipelines to be able to transport hydrogen and the new build out of dedicated hydrogen infrastructure, she said.

“Also, there’s a lot of interest in hydrogen because of its ability to decarbonize hard-to-abate sectors like transportation or heavy industry,” Wiley said. “In looking at the development of these … regions where you’re matching up local supply of hydrogen with local end uses of hydrogen, there will be opportunities for new jobs that will boost community employment. Additionally, concerns about air quality will be addressed, especially in those industrial regions.”

Leveraging existing natural gas infrastructure will also include storage, and hydrogen is a great energy storage carrier, she said. It can store energy over long periods of time and over large distances.

While there are many different colors to classify how much carbon is emitted during the production and delivery of hydrogen, GTI is interested in looking at the big picture.

“We’re very color agnostic because we recognize that you need multiple technologies and pathways to be able to produce hydrogen,” Wiley said. “The resources that you can leverage depend on where you sit geographically in the U.S.”

So, whether an area has great access to wind or solar power, or is located in a natural gas-rich region, GTI will focus on the best solutions for these differing scenarios without getting stuck on a specific color, she said.

The Hydrogen Technology Center will bring together public-private partnerships to determine how to best use this low-carbon energy carrier for storing and “time shifting” renewable energy and leveraging the existing robust natural gas storage and delivery infrastructure to facilitate the transition to a low-carbon future.

Related News

Related News

- Keystone Oil Pipeline Resumes Operations After Temporary Shutdown

- Freeport LNG Plant Runs Near Zero Consumption for Fifth Day

- Biden Administration Buys Oil for Emergency Reserve Above Target Price

- Mexico Seizes Air Liquide's Hydrogen Plant at Pemex Refinery

- Enbridge to Invest $500 Million in Pipeline Assets, Including Expansion of 850-Mile Gray Oak Pipeline

- Evacuation Technologies to Reduce Methane Releases During Pigging

- Editor’s Notebook: Nord Stream’s $20 Billion Question

- Enbridge Receives Approval to Begin Service on Louisiana Venice Gas Pipeline Project

- Mexico Seizes Air Liquide's Hydrogen Plant at Pemex Refinery

- Russian LNG Unfazed By U.S. Sanctions

Comments