April 2023, Vol. 250, No. 4

Features

First Nations: Canada’s New Infrastructure Power Brokers

By Jeff Awalt, Executive Editor

(P&GJ) — After decades of largely contentious relations between Indigenous groups and energy infrastructure developers, Canada’s First Nations are beginning to embrace the economic opportunities that pipeline and export projects can offer – a trend that could make it easier to approve and complete future projects.

The growing technical and financial participation by First Nations represent a sea change in the relationship between Canada’s Indigenous leadership and midstream projects that has been years in the making.

The seeds of change for Indigenous investment in energy projects were sown in 1997, when the Supreme Court of Canada first definitively stated that First Nations have title over their land and the resources on their land. The ruling fueled a gradual awakening of First Nations interest in economic development, which, in turn, has helped demonstrate the value of their participation in projects requiring regulatory approvals.

“When the First Nations come forward and say, ‘This is what we want to do,’ the federal government’s ability to say no is a little bit less, because they’re mandated to listen to the First Nations,” said Eric Miller, president of Rideau Potomac Strategy Group. “And the First Nations recognize that the economic opportunities and revenue they can generate for their people is significant.

“In fact, it may get harder and harder for non-First Nations projects to get permitted, because there are requirements within the regulatory system for First Nations to be listened to,” Miller said. “And if you have First Nations advocates, that changes the political and regulatory calculus when projects are being evaluated.

Opposition to infrastructure projects hasn’t stopped, of course. Authorities recently announced a reward in their search for the masked, axe-wielding protesters who forced pipeline workers from a construction site last year and attacked responding police officers. But such highly visible incidents, however rare, have helped to obscure the significant moves by First Nations leaders to increasingly embrace energy infrastructure as a source of greater prosperity for their people.

Fort Nelson First Nation Chief Sharleen Gale co-wrote in a Globe and Mail opinion column that the movement “is not about blockades and protests, but of asserting rights to unblock the creation of wealth for hundreds of First Nations that for too long have denied full participation in the Canadian economy.

“After decades of lost opportunities for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians, development no longer needs to be seen as a zero-sum game. It doesn’t have to be antagonistic and litigious,” Gale wrote with Edward Greenspan, president of the Public Policy Forum, asserting that “a new co-ownership relationship” will lower project costs and regulatory risk and raise the prosperity of all involved.”

One of the clearest indicators of that evolving perspective was the creation of the First Nations Major Projects Coalition (FNMPC) in 2016. Gale serves as chair of the collective. The coalition includes more than 130 of Canada’s First nation communities who have committed to work toward economic advancement through such projects as TC Energy’s Coastal GasLink pipeline.

“Part of why the Major Projects Coalition is particularly important is because they are serving as an advisory function, not just as an advocacy function,” Miller said, noting their involvement in the often-complex processes around project finance, rights-of-way agreements, community benefit agreements and other elements of approval and completion. “So, they are there, in essence, to be technical advisers and in doing so to facilitate the advancement of projects.”

Coastal GasLink, LNG Canada

In an early success, the coalition was instrumental in helping First Nations members reach an agreement to take a 10% ownership stake in its Coastal GasLink pipeline project, which is now more than 85% complete and scheduled for completion this year.

Coastal GasLink project involves the construction and operation of a 48-inch, 416-mile (670-km) pipeline from near the community of Groundbirch, in northeastern British Columbia, to the Shell-led LNG Canada Export Terminal, which also is scheduled for completion this year, near Kitimat, B.C. From there, the LNG will be exported to Asian markets, helping to reduce emissions by replacing high- carbon coal.

TC Energy is building the project in partnership with LNG Canada, Kogas, Mitsubishi, PetroChina and Petronas. The pipeline will be built to move 2.1 Bcf/d (59 MMcm/d) of natural gas with the potential for delivery of up to 5 Bcf/d (142 MMcm/d), dependent on the number of compressor and meter facilities constructed. The First Nations will assume its stake in the project upon completion.

Before that agreement was reached, project opponents in early 2021 blocked train lines, Vancouver’s port entrance and at least one highway in February after police dismantled a rail barricade in southern Ontario and arrested 10 Indigenous protesters. After three days of talks, Indigenous affairs ministers from British Columbia and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government reached an agreement that would address future land rights disputes while allowing pipeline construction to resume.

Coastal GasLink will provide natural gas feedstock to the Shell-led LNG Canada liquefaction and export facilities that also are due for completion in Kitimat in the latter months of 2023.

Trans Mountain Pipeline

In another sign of growing First Nations involvement, Indigenous groups including Project Reconciliation, Nesika Services and Chinook Pathways are contenders for an ownership stake in Canada’s other major pipeline project slated for mechanical completion by the end of the year – the expansion Trans Mountain (TMX) pipeline and related export facilities.

Trans Mountain, which is nearly 80% complete, was acquired from Kinder Morgan Canada in 2018 by the Canadian government plans to sell Trans Mountain after completion. The project involves the twinning of an existing 715-mile (1,150-km) pipeline originating near Edmonton, Alberta, and extending to Burnaby, British Columbia.

The 590,000-bpd expansion will nearly triple the flow from Alberta’s oil sands to Canada’s Pacific coast, opening access to Asian markets. It includes more than 600 miles (980 km) of new 36-inch pipe and 120 miles (193 km) of reactivated pipeline, along with 12 new pump stations and 19 new storage tanks at existing terminals.

RELATED: Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion Project to Nearly Triple Current Capacity to 890,000 bpd

While the First Nations have continued to express interest in acquiring a stake in the project, potentially with Pembina, soaring costs for the project have raised concerns about their ability to make a suitable return on the investment. In a March update, the federal corporation building Trans Mountain said the projected cost of the oil pipeline’s expansion had jumped 44% from last year’s estimate to C$30.9 billion (US $22.35 billion).

In February 2022, Trans Mountain had increased the cost estimate to C$21.4 billion (US$15.9 billion), up from C$12.6 billion (US $9.3 billion) in 2020 and C$7.4 billion (US$5.5 billion) in 2017. Following last year’s jump, the Canadian government said it would halt any further public funding for the project. Trans Mountain said it is in the process of securing external financing to fund the remaining cost of the project, which is now expected to start shipping oil in the first quarter of 2024.

Cedar LNG

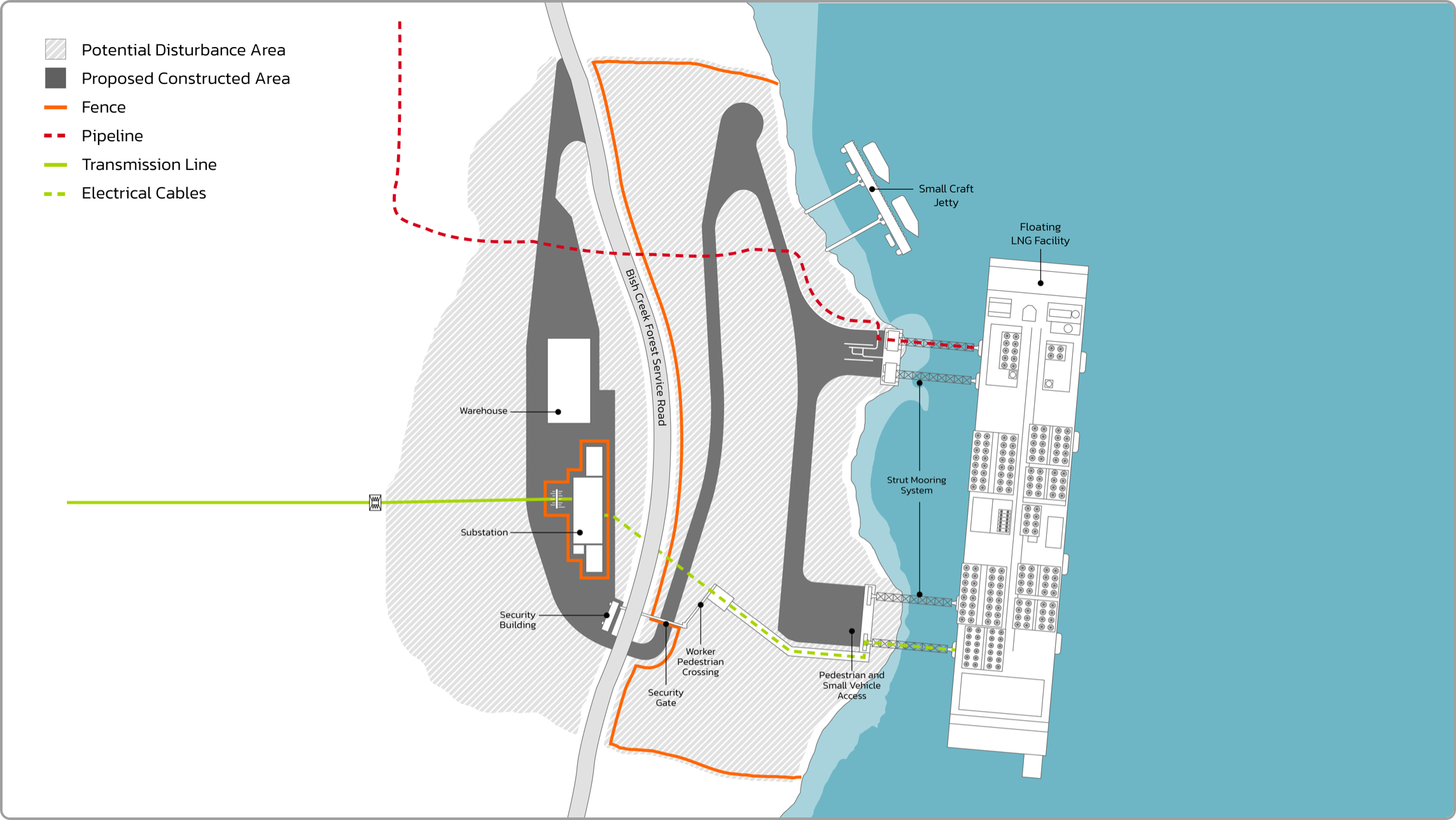

In an indication that projects with First Nations support may have a smoother track to completion, the 3 mtpa Cedar LNG Project on March 14, Cedar LNG became Canada’s first Indigenous majority-owned LNG Facility to receive an Environmental Assessment Certificate from the Provincial Government. The Federal Government issued a positive Decision Statement for the project the following day.

Cedar LNG is under development by the Haisla Nation and Pembina Pipeline Corporation. Natural gas will be transported via Coastal GasLink to the Cedar LNG site, which will be interconnected to the existing BC Hydro transmission system, making Cedar LNG one of the lowest-carbon-intensity LNG facilities in the world.

The $3 billion project has already entered into an MOU for a 20-year liquefaction services agreement with ARC Resources. A final investment decision is expected in the third quarter of 2023, with commercial operations beginning in 2027.

Taken as a whole, the level of Indigenous involvement in oil and gas midstream projects represents “a game-changer relative to where we were 10 or 15 years ago,” said Miller, a fellow at both Ottawa’s Canadian Global Affairs Institute and Washington’s Woodrow Wilson Center who serves on the external advisory committee on international trade policy to Canada’s Deputy Minister of International Trade.

“As energy companies and First Nations build a deeper and closer relationship, it will become a more common practice for how projects are built in Canada,” Miller added. “Where we’ve suffered from this uncertainty in stops and starts in the past, perhaps with First Nations ownership and involvement this becomes a formula for successful project developers.

Comments