December 2022, Vol. 249, No. 12

Features

Cross-Border Pipelines Seen as More Critical to Africa’s Future

By Shem Oirere, P&GJ Africa Correspondent

(P&GJ) — Africa’s domestic demand for both oil and gas is estimated at 75% of the region’s total production, creating opportunity for development of efficient cross-border pipeline networks to ship fuels aimed at plugging the deficit especially to landlocked countries.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) said in its 2022 Africa Energy Outlook that new deals were signed recently to deliver Algerian gas to Europe, “along with renewed momentum to develop and expand LNG terminals in Congo, Mauritania and Senegal.”

One of the outcomes of the raging Russian-Ukraine conflict is the resolve of the European Union (EU) to halt Russian gas imports by 2030, a move that places Africa in an advantageous position to supply an extra 1.1 Tcf (30 Bcm) of gas over the next eight years.

This trend highlights the critical role cross-border oil and gas pipelines can play in integrating not only the intra-Africa energy trade but also in opening up bigger market opportunities for hydrocarbon resource producers in Africa.

Cross-border oil and gas pipelines in Africa, though at times operating between different legal and regulatory frameworks, have helped deepen economic cooperation across the continent’s borders with the establishment of African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), a free trade area encompassing most of Africa, expected to strengthen the region’s trade in oil and gas.

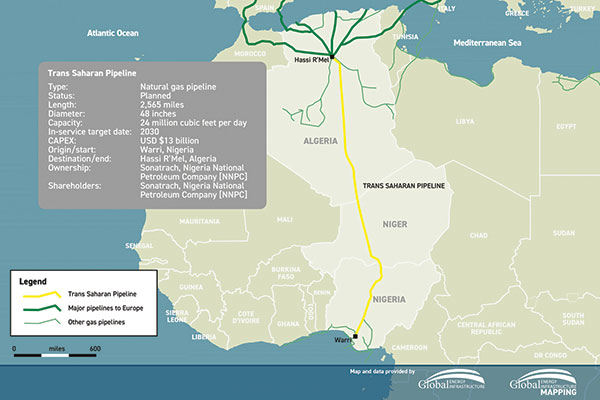

Some of the proposed, ongoing, or operational cross-border oil and gas pipelines in Africa include the Trans-Saharan gas pipeline, Niger-Benin crude oil pipeline, Nigeria-Morocco gas pipeline, West Africa Gas Pipeline, the East Africa Crude Oil Pipeline, South Sudan-Sudan pipeline and the Mozambique-South Africa gas pipeline.

However, recent oil and gas production, consumption and export trends could undermine, in the short-term, optimizing the efficiency of the existing cross-border pipelines in Africa.

For example, the IEA says Africa’s export-oriented oil and gas market could be getting depressed because of the volatility of the “global demand trajectories, competitive dynamics in export markets and prices.”

In 2020, IEA noted there was an abrupt dip in output and “the pace of recovery in 2021 was slower than in most other parts of the world,” except for Libya whose production surged strongly in 2021 to 1.2 MMbpd. The country’s oil production had collapsed in 2020 because of the ongoing political turmoil.

IEA predicts a fall in oil production “steadily over the period to 2030 due to a combination of slower growth in global oil demand, worsening financing conditions and project delays.”

Furthermore, IEA says, “lower world oil demand and lower prices push down total African oil production from over eight million barrels a day in 2019 to around six million barrels a day in 2030.”

Output in Angola and Nigeria is also being suppressed by the growing number of maturing oil and gas fields, as well as unpredictable fiscal regimes is undermining despite the countries being Africa’s top producers.

In Angola, IEA said, “oil production continues to trend downward as new projects are insufficient to stem declines in maturing fields” while Africa’s largest oil producer Nigeria is struggling to “stem the slump in output as uncertainties surrounding fiscal terms and high operational risks hamper investment in large projects needed to offset output declines at existing fields.”

Because of the disruption of the global oil and gas supply chains, especially at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, major oil development projects were put on hold in countries such as Kenya, Senegal, Uganda and Senegal and Ghana according to the IEA. These countries, prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, had unveiled respective cross-border pipelines whose development is also on hold.

In 2016, Uganda and Kenya agreed to construct two cross-border crude oil pipelines, one from Hoima in Uganda through Lokichar to Lamu in Kenya and the other from Hoima to the port of Tanga in Tanzania. Uganda later abandoned the plan and opted to partner with Tanzania to implement the latter project.

“While Uganda recently reached a final investment decision on the USD 10 billion Lake Albert development project, the timeline for other new projects in these countries remains uncertain due to persistent delays, technical problems and weak regulation,” IEA observed.

Nevertheless, in February, Tanzania and Uganda signed the $3.5 billion East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP) tripartite project agreement for the construction and operation of the 898-mile (1,445-km) cross-border crude oil pipeline. At least 80% of the pipeline, or 693 miles (1,115 km), will run through Tanzania.

The transboundary pipeline project’s shareholders include Total of France (72%), the China National Offshore Oil Corporation (8%), the Uganda National Oil Company (15%) and the Tanzania Petroleum Development Corporation (5%).

There are other proposed cross-border oil and gas pipelines, including Nigeria-Morocco gas pipeline, African Renaissance Pipeline (ARP) and the Trans-Saharan natural gas pipeline from Nigeria to Algeria

Promoters of the proposed cross-border are optimistic the viability of the projects would outlive emerging oil and gas production, export and consumption trends that point toward suppressed volumes.

A recent report by PricewaterhouseCoopers Ltd. (PwC) predicted a 25% decline in overall oil production in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) between 2021 and 2030 due to projected waning global demand that could stifle potential investment, especially in the development of new oil fields.

Net oil exports from the region have also contracted to 2.4 MMbpd, an equivalent of 40% since the 2010s “on the back of dwindling production and surging demand … This trend is projected to continue, with the region becoming a net importer of oil in the mid‐2030s,” PwC said.

Additionally, the shrinking refining systems in SSA means several crude processing plants, such as Kenya Petroleum Refineries Limited (KPRL), have since ceased operations and transformed into a fuel import terminal. Kenya Pipeline Company has since acquired KPRL to enhance the petroleum products supply chain in East Africa.

Elsewhere, South Africa’s biggest chemical company, Sasol, has been operating the 537-mile (865-km) gas pipeline that conveys natural gas from Mozambique’s Temane and Pande gas fields to Secunda in South Africa. Sasol also completed, in 2015, a $110 million loop line project, 80 miles (128 km) of pipeline that runs parallel to the main pipeline and increases capacity in the region.

Sasol and the governments of South Africa and Mozambique, through their respective national oil companies, own the pipeline through a joint venture entity, the Republic of Mozambique Pipeline Investments Company.

South Africa–based clean energy developer and operator, Gigajoule International (Pty) Ltd., has also proposed a cross-border natural gas pipeline to connect Mozambique’s city of Maputo to South Africa to supply feed stock for gas-fired power plants “positioned near the pipeline in both countries.”

Furthermore, a joint venture comprising Mozambique’s national hydrocarbon company (ENH) and a private sector consortium that includes South African oil and natural gas company SacOil, the China Petroleum Pipeline Bureau has proposed to build the Africa Renaissance pipeline (ARP), an $8 billion, 1,615-mile (2,600-km) pipeline with a capacity of 635 Bcf per year.

The pipeline would ship natural gas from Mozambique’s Rovuma Basin to South Africa’s Gauteng province reports. Initial plans indicate the project would commence in 2024 and be completed in 2026.

Additionally, Profin Consulting Sociedada Anónima has proposed to build the Africa Renaissance pipeline (ARP), a $8 billion, 1,615-mile (2,600-km) pipeline with a capacity of 635 Bcf/y (18 Bcm/y). The pipeline will ship natural gas from Mozambique’s Rovuma Basin to South Africa’s Gauteng province reports. Initial plans indicate the project will commence in 2024 and be completed in 2026.

However, in April 2022, Sasol, which expressed interest in acquiring a stake in the pipeline, changed its mind and pulled out of the venture, which when complete will connect to the natural gas fields in Mozambique that are partially owned by TotalEnergies SE and ExxonMobil.

Sasol recently announced the shedding of 30% of its equity stake in the Republic of Mozambique Pipeline Company (ROMPCO). The transaction closed on 29 June 2022 leaving the company with a 20% equity interest.

But even as the cross-border oil and gas pipeline segment shows potential for growth, operation of some of the existing pipelines continue to face challenges that threaten to disrupt their smooth operations.

For example, operational challenges facing the West Africa Gas Pipeline (WAGP) is said to have denied Ghana an opportunity to save up to $14 billion from the development of the TEN (Tweneboa Enyenra and Ntomme) and Jubilee extension fields according to an analysis by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID).

“Benin and Togo are both currently suffering financially as a consequence of the supply issues in the WAGP,” USAID said.

The Agency estimates the two countries can easily save up to $5 billion if the supply issues with WAGP were resolved and gas flows at high and predictable volumes.

“Unfortunately, the pipeline is being utilized below its potential despite the clear benefits it could provide to Benin, Togo and Ghana,” USAID added.

An increase in Nigeria’s domestic demand for gas has attributed to some of the problems faced by WAGP and “has increased more than the production, thus reducing the gas availability for WAGP,” as well as the tendency by Ghana’s purchaser, Volta River Authority, to default on payments.

“Addressing these challenges would see enormous savings for Ghana, Benin and Togo and mitigate against the need, in the short-term at least, for them to pursue other import options such as LNG [liquefied natural gas],” USAID noted.

With Africa’s proven oil and gas reserves estimated at 125.1 billion barrels and 455 Tcf (13 Tcm), respectively, the continent will need more cross-border pipelines for oil and gas even as the region seeks for an integration of the different legal and regulatory frameworks through initiatives such as AfCFTA.

As the World Bank correctly puts it, the free trade area is the largest in the world and connects nearly 1.3 billion people across 55 countries with a combined gross domestic product (GDP) valued at $3.4 trillion. There is potential for growth of cross-border oil and gas pipelines.

Comments