April 2022, Vol. 249, No. 4

Features

With Leases a Key, Can the Bullishness Return?

By Richard Nemec, Contributing Editor

At the November 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26) in Scotland, President Joe Biden urged all the world’s largest nations to step up to the climate change challenges in this decade with “action and solidarity.” He also outlined what his administration intends to do to meet the challenges under the PREPARE (Presidential Emergency Plan for Adaptation and Resilience) effort.

It will “mobilize the U.S. government resources and expertise” in support of climate adaptation efforts for more than a half a billion people worldwide, according to the president.

Later that same month, the Biden administration gave a green light to one of the largest offshore lease sales ever in the Gulf of Mexico (GOM). Federal Lease Sale 257 concluded Nov. 17 last year, pulling in $191 million in proceeds from winning bids on 308 lease blocks.

Earlier in 2021, the courts had overturned Biden’s executive order banning new lease sales offshore in federal waters. GOM lease activity was re-activated in short order, but a little more than two months later, in late January, another federal judge invalidated the lease sales results, contending that the Biden administration failed to properly account for the auction’s climate change impact, reinjecting uncertainty over the future of the U.S. federal offshore drilling. Offshore advocates expressed concerns about the legal setback.

In early February, the American Petroleum Institute (API) challenged the court’s sale rejection in the U.S. Court of Appeals in Washington, D.C.

National Ocean Industries Association (NOIA) President Erik Milito quickly issued statements offering an historic perspective on the massive sale, noting that it “reflects the U.S. Gulf of Mexico’s record as a low-carbon energy basin.” Milito said that energy companies are increasingly making decisions incorporating climate and ESG (environmental-social-government) factors and seeking to produce oil from regions with a low-carbon intensity, aspects the latest federal court setback apparently did not consider.

API raised some of these issues in its appellate court filing that calls for “preserving American energy leadership.”

“With its world-class infrastructure and prospective resources, the GOM provides an incredible value proposition in society’s efforts to tackle climate change while preserving jobs and economic growth and mitigating against inflationary energy prices. While providing a lower-carbon energy alternative to oil produced by foreign, higher-emitting producers like Russia and China, the GOM supply chain is also contributing to the build-out of the American offshore wind sector and is investing in emissions mitigation solutions such as carbon capture, utilization and storage [CCUS],” Milito said.

International research and consulting firm Wood MacKenzie (WoodMac) describes the oil and natural gas majors as transitioning their operations to address climate change with an ESG emphasis.

The GOM is no exception, according to WoodMac’s Justin Rostant, principal analyst for the U.S. Gulf of Mexico.

“Even though most of the largest producers are prioritizing energy transition into their portfolio, they continue to do so using a multifaceted approach,” Rostant said. “Highlighting U.S. GOM as a core region, they recognize that its barrels have low emissions and high margins and will continue to attract investments that can help fund investments in the renewables space.”

Overall, the Gulf of Mexico has a carbon intensity that is about one-half the carbon intensity of other onshore areas. Deep water, which accounts for 92% of all GOM production, is the lowest source of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions of all oil-producing regions. Not to mention, without the Gulf, increased transportation of oil to U.S. consumers would lead to additional emissions.

But Judge Rudolph Contreras of the U.S. District Court of the District of Columbia disallowed the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management’s sale after Earthjustice challenged the sale on behalf of four other environmental groups, arguing the Interior Department was relying on a years-old environmental analysis that did not accurately consider GHG emissions that would result from the development of the added blocks.

In contrast, the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) describes GOM and the onshore Gulf as one of the world’s most important regions for energy resources, noting last year in its Short-Term Energy Outlook that it expects the federal GOM to increase production over 2021–22.

“By the end of 2022, 13 new projects could account for about 12% of total GOM crude oil production, or about 200,000 bpd,” EIA analysts noted. EIA expects up to nine new GOM projects this year and a move back toward the 2019 level of production pre-pandemic (1.9 MMbpd).

In a 2022 energy outlook, the CEO of API Mike Sommers highlighted the industry’s work with the Biden administration to revive lease sales on and offshore, and API was part of a lawsuit seeking to resume the sales.

“We’re hopeful another lease sale will be held in the GOM as quickly as possible and get our offshore operators working in a manner consistent with current federal law [requiring quarterly sales each year],” Sommers said in early January.

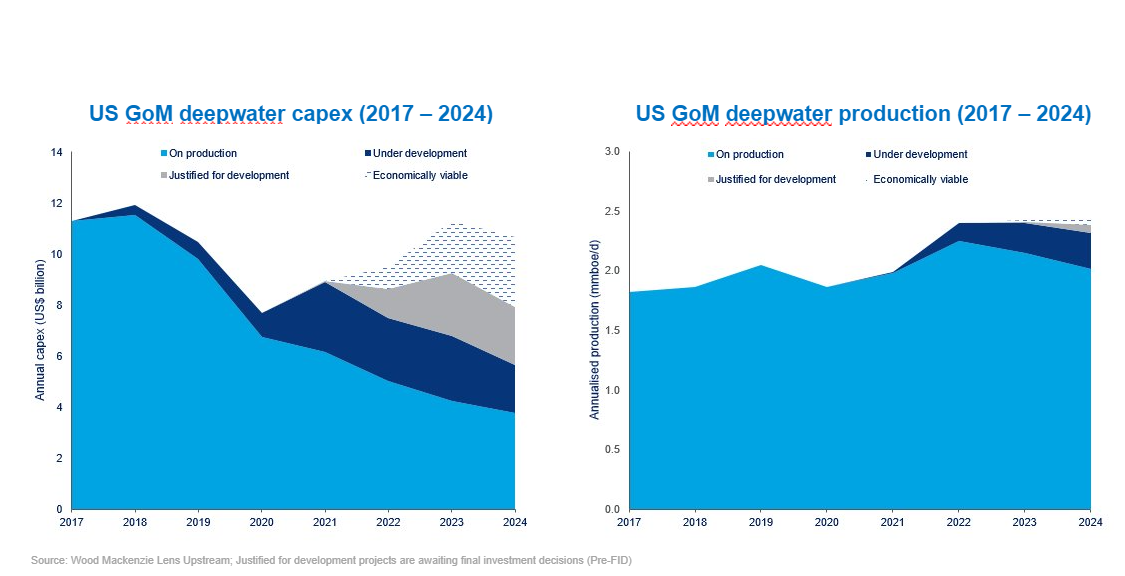

In mid-January this year, WoodMac’s vice chair for the Americas Ed Crooks went as far as to predict record GOM production in 2022 as part of an opinion column published on the firm’s website. “Platforms coming on stream will take U.S. deep-water output to a record high in 2022, but new entrants have been wary of moving into the region,” Crooks wrote.

Pre-pandemic, the GOM production was at about 1.7 MMbpd, and conservative prospects in 2022 call for it to be in the range of 1.7 to 1.8 MMbpd, remaining about 15% of the U.S. overall production, which is approaching 12 MMbpd.

According to most analysts, 80% of the Gulf production comes from the Big Three – BP plc, Royal Dutch Shell, and Chevron Corp. Some of the smaller operators went bankrupt during the 2015–16 global oil price crash and again more recently during the COVID-19 pandemic, said Sajjad Alam, vice president/senior credit officer at Moody’s Investors Service. “You’re left with most of the GOM production coming from the three large super-majors.”

“They determine what will happen with production in the region,” according to Alam. He doesn’t expect a lot of exploration and wildcat drilling in the Gulf for the near future, noting GOM “is all brownfield development of existing facilities where the costs are relatively low, and the geologic risk is fairly certain.” There are thousands of wells in the GOM between the shelf and in deep water, and for offshore plays, generally longer development times and bigger investments are required.

“The production trend should be mildly positive in the GOM through 2023 based on firm oil prices over the next 18 months,” Alam thinks. “But I wouldn’t frame it as ‘bullish,’ which has a stronger positive connotation with respect to capital allocation. The industry has steadily moved towards shorter-cycle assets since the 2015–16 downturn, and this trend is unlikely to reverse unless there are much stronger price signals and reduced regulatory pressures/uncertainty, which seem unlikely given the global push to reduce the use of oil.”

WoodMac’s Rostant is more bullish, noting that 2022 production in U.S. GOM is forecasted to increase by more than 15% as several new projects start production during this year. He cites BP’s Mad Dog Phase 2 and Murphy Oil Corp.’s Khalessi/Mormont as two major projects expected online around the middle of 2022, adding 75,000 boe/d.

“Shell’s Vito may come online by the end of 2022, but that could slip into 2023 if there are any more schedule disruptions,” Rostant said.

But there are also other fields such as Power Nap and Samurai that should start up and add 45,000 boe/d production this year, he noted.

Shell sanctioned its Whale development, committing $4.2 billion to develop the 440-million-boe field, continuing to drill exploration and appraisal wells and announcing 25 wells in the next three years. Chevron sanctioned the Anchor project in 2019 and is expected to sanction its Ballymore discovery in 2022, according to WoodMac.

Chevron is also partnered with Shell in the Whale project. Chevron’s share of capex for these three projects is approximately $10 billion. Similarly, BP is the operator of the Mad Dog Phase 2 project that will start production in 2022, and last year it successfully started production at the Manuel field.

“BP continues to drill new infill production wells at Atlantis Phase 3 and Thunder Horse Phase 2 expansion projects,” Rostant said.

Writing in mid-January this year, WoodMac’s Crooks couched his bullish predictions for record production with some words of caution. While citing his firm’s projections for an average production of about 2.3 MMboe/d, Crooks noted that although GOM costs and the low-carbon intensity of production make it a highly competitive basin internationally, “the expected long-term transition away from fossil fuels may be having an effect on activity; companies that are active in the region are generally doing very well out of it, but there has not been a rush of new entrants seeking to exploit those opportunities.”

In recent years, GOM operators have cut costs significantly to make projects viable at much lower oil prices, typically around $40/bbl. In January, Brent crude prices hit around $85/bbl, which prompted analysts to predict new projects would likely generate healthy returns.

Nevertheless, the growing caution by Crooks and other energy analysts was underscored in a 2021 assessment by the International Energy Agency (IEA), which concluded that the world must stop developing new oil, gas and coal fields today or face a dangerous rise in global temperatures.

An organization that has spent four decades working to secure oil supplies for industrialized nations, IEA has published a roadmap for achieving net-zero global carbon emissions by 2050 through what it calls “stark terms.”

IEA insists that annual gains in energy efficiency must happen three times faster over the next decades; installations of photovoltaic panels would have to rival the size of the world’s biggest solar park every single day until 2030; and “within three decades, the role of fossil fuels should reverse entirely – from 80% of global energy needs today to barely a fifth by mid-century.”

The 2022 Gulf Coast Energy Outlook by the Louisiana State University (LSU) Center for Energy Studies echoes the IEA, noting that decarbonization may lead to near-term challenges for the Gulf region. Over the forecast horizon, however, decarbonization “will create considerable opportunities for continued regional capital investment.”

The LSU outlook envisions Gulf Coast industrial expansion that “creates opportunity for leadership in developing liquid fuels, chemicals, plastics, fertilizers and other products historically derived from fossil fuels, with lower, even net-zero, GHG emissions.” It views decarbonization as creating more opportunities for the Gulf.

GOM boosters, such as NOIA, also envision the Gulf as a tool to address climate change in the interim decades leading up to a zero-carbon energy world. They argue that “innovators” are continuing the advancement of climate change solutions and producing low-carbon barrels of oil by continuously deploying new technologies and processes. NOIA calls GOM “a climate change asset” that is allowing domestic and global energy demand to be met in a safe, affordable and reliable manner.

In recent years, rig counts in the Gulf have fluctuated from more than 40 before the global price crash of 2014–15 to 15 coming out of the pandemic. Pre-pandemic there were 17 to 18 rigs operating.

“After the downturn, the rig count became permanently reduced and many companies went bankrupt, and a lot of companies shed their assets and got out of GOM,” Moody’s Alam said. “It rarely got above 25 and pulled back to 20 or 21 in 2016.”

Today, WoodMac views the glass as half-full in terms of GOM rigs, counting 19 deep-water floaters in mid-January and projecting up to 22 rigs at the end of this year. (Alam basically agreed with this projection.) Fifth- and sixth-generation drillships are now preferred in the region as operators take advantage of advances in drilling efficiency.

“The latest sophistication added to deep-water drillships headed to the U.S. GOM is 20,000-psi technology required to complete wells in certain high-pressured fields,” Rostant said.

Analysts also agree that operating costs and investment in GOM will rise this year, but they will still be relatively low in a historic sense. Two factors are helping inject more cost increases – commodity price increases and costs went through what some analysts call “a massive deflation from 2015 to 2018,” and they have stayed low relative to prices these days. During that downturn period, rig costs dropped by 40% or more.

The cost of development relative to where prices are is considered low. A deep-water drilling rig pre-2015 would have cost $600,000/day; today that same rig is about $200,000 to $250,000/day. “It’s a fraction of what it was before the 2015–16 downturn.”

At the same time, analysts say investment levels have increased. “New final investment decisions [FID] on capex went from $500 million in 2020 to $8.5 billion in 2021,” according to WoodMac statistics. “We expect FID capex commitments of $12 billion in 2022.”

The GOM is experiencing some cost inflation due to the pandemic. Costs of steel and fuel and employees are all up. “There is some cost pressure that is going to be fairly widespread, but on a relative basis when you look back in history, the overall cost structure for producers is still fairly low,” Alam said.

For offshore development generally and the GOM specifically, technology remains an important component for continued success in the future. “It is pretty amazing how much research and development [R&D] goes into the industry every year,” Moody’s Alam said. “Having said that, the impact from a cost perspective is hard to quantify. It doesn’t show up until a company actually begins producing positive results.

“Interestingly, in the oil and gas technologies, the seismic side has had a lot of innovations, but in terms of the tools used, operators still have to drill through rocks using more intelligent drill bits, guidance sensor systems to stay within the pay zone and do things faster, but it is still exceedingly difficult to determine exactly how much of the cost improvement is coming from technology. I’ve never seen companies explain this in convincing ways.”

In the GOM, most of the big producers are the majors and they typically have the best R&D. “Those companies [BP, Shell and Chevron] have very, very good track records in terms of using the top technology in the industry, particularly in offshore wells that can cost sometimes $200 to $300 million,” Alam said.

Beyond technology, the aspects of future regulation and the attitude of Mexico’s current governmental officials loom large over the GOM. Anti-private investment sentiments and a move to diversify Mexico’s government-run energy company Petroleos Mexicanos (Pemex) provide strong uncertainties for Mexico’s future development of its interest in the GOM.

The consensus among analysts is that Mexico could and should do more in the Gulf, but it may not be a priority for the current national government and its goals for remaking Pemex.

At the outset of 2022, Mexico’s government appears quite positive about crude production, which estimates it at 1.9 million bpd, according to Adrian Duhalt, postdoctoral fellow in Mexico energy studies at the Baker Institute’s Center for Energy Studies at Rice University in Houston.

“This is an important leap with respect to 2021 reports of 1.6 MMbpd from the GOM. What worries me is that Pemex has its hands full of projects, from upgrading refineries and buying the U.S. refinery at Deer Park, Texas, to being involved in the liquid petroleum [LPG] market and fertilizers,” Duhalt said. “And that may compromise its crude oil production prospects, its most important and profitable business. Considering all of the Pemex commitments, maintaining production levels in the GOM would be in itself an achievement.”

Mexico’s GOM section in the Perdido area increased its activity from one well spud in 2020 to four in 2021, with important prospects drilled like Shell’s Xochicalco, Chimalli and Xuyi, and the international exploration and production (E&P) CNOOC (China National Offshore Oil Corporation) Limited’s Xakpun. Unfortunately, the anticipated discoveries have not been found, according to WoodMac’s Diego Alviso Becerril, senior research analyst, Upstream Latin America and Mexico.

“We do not see an increased activity in the area after the results of last year. All exploration plans considered additional appraisal wells in case of discoveries that did not happen; however, there are still wells committed to be drilled,” Becerril said. “CNOOC has one well expected this year to comply with its commitments in Area 1, and Shell has still two wells pending in blocks PG01 and PG04, where they could have another attempt to find the discoveries, they were looking for in 2021.

“Pemex also has one well committed in block PG05, where despite the fact that deep water is not an area of focus for Pemex, it has proposed a considerable increment in its 2022 budget for this area. After the mentioned wells, there would not be any other commitment to increase drilling in the area unless a commercial discovery is found, and a project moves into an appraisal strategy.”

Alam thinks Pemex has a lot of issues to deal with in 2022, and the current federal government wants to keep more of its crude in the country to meet its own field demand.

“Mexico’s production has been declining and has been stabilizing somewhat at this point, but Pemex is the most highly levered large oil producer in the world,” he said. “And the politics there makes it difficult for entities to invest adequately. From Mexico’s side, there is not going to be a whole lot more in GOM. The Mexican government is trying to auction off blocs to foreign companies.”

Firms that secured contracts under the oil and gas bidding rounds hosted by the previous Mexican national government continue to make strides. Of the 111 contracts awarded, 31 are already producing while the rest are in the exploration phase. “What these numbers tell us is that these firms are bullish about their own existing projects,” Duhalt said.

A Mexican citizen with academic affiliations on both sides of the U.S.–Mexico border, Duhalt is skeptical of the current national government’s appetite for private investment. Apart from price fluctuations, he views Pemex finances as a major uncertainty this year, which could constrain the capacity of the government entity to invest and therefore hit its production targets.

“However, it remains to be seen if the fact that the government wants Pemex to wear several hats at the same time, it would eventually have implications for the GOM prospects,” Duhalt said. A possible mitigating strategy for the Mexicans would be “to share the risk and the burden to invest with the private sector,” he said. However, that is not an option for the current government.

Adding to the Gulf’s future uncertainty is the U.S. regulatory environment where analysts like WoodMac’s Rostant see plenty of potential concerns.

“The major uncertainty comes from the policies of the Biden administration,” he noted. “We have seen the Democratic party proposing new policies and regulations that are more restrictive to the industry. For instance, in 2021, Biden issued an executive order to ban new lease sales in U.S. GOM deep water, which was later overturned in the courts. Future lease sales in U.S. GOM will continue to be at risk until we get a change in the ruling party in Congress or the executive branch.”

Richard Nemec is P&GJ’s contributing editor based in Los Angeles. He can be reached at rnemec@ca.rr.com.

Comments