June 2020, Vol. 247, No. 6

Features

How Pipelines Are Solving Texas’ Flaring Problem

By Nicholas Newman, Contributing Editor

Millions of dollars’ worth of Texas gas is being lost in flaring and venting. In parallel with burgeoning oil and gas output, the amount flared and vented rose to 650,000 mcf/d in 2018, as recorded by the Texas Railroad Commission (TRC).

Although flaring is more common than venting, both routinely occur during oil and natural gas development. Natural gas flaring is the process of combusting natural gas at the well-head using a dedicated flare.

Venting refers to the direct release of gas into the atmosphere and is often banned or restricted. When possible, flaring is preferred because methane, the main component of natural gas, is a potent greenhouse gas, more potent than carbon dioxide, which is the main product of flaring.

The reality is that increases in oil output automatically lead to increases in associated gas production. In the Permian Basin alone, oil production rose from just 719,480 bpd in 2008 to 2.73 MMbpd in 2019.

Likewise, shale gas output increased from 3.54 MMcf/d in 2008 to 10.96 MMcf/d in 2019, according to the TRC. Not surprisingly, this burgeoning Permian output in such a short space of time overwhelmed the existing gas offtake capacity.

To curb the amount of flaring in the Permian basin and to relieve congestion requires significantly more gas offtake pipeline capacity. Fortunately for both the environment and production companies, the Gulf Coast Express has just come online, and the Permian Highway Pipeline and the Whistler Pipeline are underway, possibly to be joined by the Permian Pass Pipeline in the future. These pipelines could provide an additional daily offtake for 8 Bcf for Texas gas.

Gulf Coast Express Pipeline

The $1.75 billion Gulf Coast Pipeline (GCX), a joint venture between Kinder Morgan and Targa Resources, came online as recently as September 2019. It transports 2 Bcf of gas per day to refineries and export markets located along the Gulf of Mexico coast and, via the Kinder Morgan border pipeline, supplies gas-hungry Mexico.

The 42-inch GCX pipeline transports natural gas from the Waha area of the Permian Basin in West Texas to Agua Dulce near the southern part of the Texas Gulf Coast. The mainline transmission pipeline originates at the Waha Hub near Coyanosa and ends 447 miles (719 km) away in Agua Dulce. In addition, a 35-inch branch pipeline of about 50 miles (80 km) in length transports the natural gas processed at Targa’s facilities in the Midland Basin area to the mainline pipeline network.

Permian Highway Pipeline

Under construction is Kinder Morgan’s $2 billion 42-inch, 2-Bcf/d Permian Highway Pipeline (PHP).

At 430 miles (692 km) in length, it begins at Waha like the Gulf Coast Express, but ends further north, at Katy near Houston, which is one of Texas’ leading gas storage hubs with a total working capacity of 21 Bcf. Thanks to COVID-19, the planned completion date at the end of 2021 could be missed.

Whistler Pipeline

Subject to the receipt of the necessary regulatory approvals and the impact of COVID-19 on construction activity, the Whistler Pipeline is scheduled to begin operations in the third quarter of 2021.

This $1.24 billion project is backed by a consortium made up of MPLX LP WhiteWater Midstream and a joint venture between Stonepeak Infrastructure Partners and West Texas Gas.

The 42-inch intrastate pipeline is designed to transport 2 Bcf/d of natural gas for 450 miles (724 km) from the Waha Hub in the Permian to the Agua Dulce hub in South Texas. In fact, it roughly follows the route of the GCX Pipeline but has the merit of making several important interconnections.

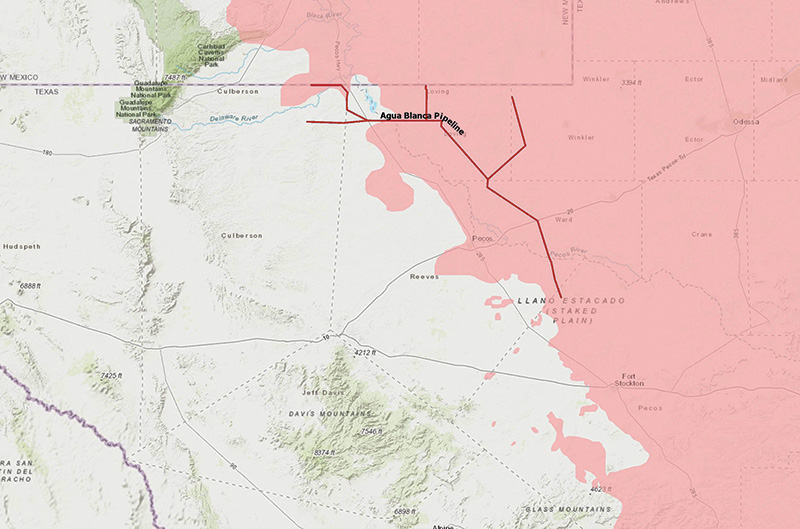

Whistler will have a 50-mile, 30-inch branch pipeline into the Midland Basin, where it will interconnect with various processing plants and pipelines. At Waha, Whistler will have a direct interconnect with the 1.4-Bcf/d Agua Blanca Pipeline, a joint venture of WhiteWater, MPLX and Targa Resources. At Agua Blanca, the Whistler Pipeline will interconnect with Kinder Morgan’s El Paso Pipeline, and there are plans for a future interconnect with GCX.

Permian Pass

Houston pipeline operator Kinder Morgan is currently seeking customers to assure the commercial viability of its planned 2-Bcf/d capacity Permian Pass Pipeline, which is designed to take natural gas from the Permian Basin of West Texas onward to the Gulf Coast. The exact route is still being studied, but it would begin in the Permian Basin of West Texas and New Mexico, extending eastward across Texas to near the Sabine River, the location of the liquefied natural gas (LNG) export terminals.

In a recent investor presentation, Kinder Morgan Chief Strategy Officer Dax Sanders said conversations with potential shippers continue for Permian Pass, but no contracts have been signed to date. He added that the project will not be sanctioned without “solid take-or-pay contracts” that carry terms of at least 10 years.

Prospects for this new pipeline project are not helped with U.S. Henry Hub gas prices averaging just $1.94 per MMBtu in 2020, which are forecast to rise to only $2.43 per MMBtu next year, due to gluts of both domestic natural gas and LNG.

Analysts expect global market fundamentals will remain loose through 2022 before prices tighten significantly as LNG demand growth outpaces liquefaction capacity because of more delays in project sanctioning. In which case, a postponement rather than abandonment is to be expected.

Who Will Benefit?

There are multiple and diverse beneficiaries of these projects besides the pipeline companies, investors and customers. Even drillers that didn’t sign up for space on these new pipelines will benefit, because additional takeaway capacity should reduce the region’s gas glut and boost prices.

Similarly, additional pipeline capacity will help many local companies that buy raw gas from producers for processing and sell to end-users. In addition, the new mainline transmission operators will gain by transmitting gas to higher-priced Gulf Coast markets.

The reality of a rock-bottom oil price is slowing oil output growth and the need for flaring and venting.

However, a significant reduction in gas flaring and venting would require that the TRC introduce regulations to discourage it, while, at the same time, encourage investors like TransCanada, Enbridge and Kinder Morgan to develop new pipeline export capacity.

Comments