August 2018, Vol. 245, No. 8

PPSA 2018 Pigging Update

Preparing Pipelines for Successful In-Line Inspection

By P.J. Robinson, T.D. Williamson, Tulsa, OK,

Between pipeline cleaning and in-line inspection (ILI), it is customary to run a gauge pig to determine if there are bore restrictions that can limit the piggability of the ILI tool. Gauge pigs provide insight into some conditions inside the pipe, but not all of them. They’re not intended to measure pipeline cleanliness or indicate if debris has built up to the point that it will impair the inspections tool’s data-gathering capabilities.

Recently, a natural gas operator believed their line was prepared for ILI after running a foam proving pig and a gauge pig. However, because the company hadn’t done any pipeline cleaning – and the line had little pigging history – it was possible there was enough debris in the pipe to cause expensive problems during the ILI run, including degraded data or tool damage. At the recommendation of the T.D. Williamson (TDW) global pipeline solutions team, the operator executed a more stringent cleaning plan that helped ensure a successful inspection.

Prior to ILI, it is standard practice to run a gauge pig to verify the internal geometry of the pipeline and determine if there are bore restrictions that can limit the piggability of the ILI tool. Gauge pigs can indicate a variety of operational issues — partially closed valves, elbow bends, pressure variations and launch or receiving errors, to name a few.

However, a successful gauge pig run with no plate deflections – meaning the pig didn’t encounter any obstructions or diameter reductions – doesn’t always indicate that the ILI run will be successful. For one thing, gauge plates are usually 95-98% of the inside diameter of the pipe. That leaves 2-5% of space where scale and debris might be attached to the pipe wall. Residual debris on the pipe wall that isn’t affected by the gauge pig can build up on the ILI tool, potentially causing serious repercussions: damaged sensors, odometers and other components, degraded data or a stuck tool, all leading to ILI failure.

A failed inspection costs the pipeline operator both time and money — resources must be re-deployed, flows slowed to facilitate optimal inspection tool speed and third-party contractors engaged to provide support services associated with transporting a working computer (the ILI tool) through an operating pipeline.

According to the Pipeline Operators Forum: “Getting the ILI right the first time will increasingly be important as the oil and gas industry tackles the more difficult lines. Failure to achieve first run success will result in additional costs on ILI activities with individual project costs potentially many times higher than the original budget. These costs include additional runs; associated lost production; tool repairs or recovery.”1

Based on the results of a successful gauge pig run that delivered 5 gallons (19 liters) of debris with no deflections, a natural gas pipeline operator was ready to perform ILI on 4.8 mile- (7.7-km) pipeline segment without additional cleaning to remove any residual debris.

The problem was, a gauge pig tells an operator only part of the story: whether bore restrictions are present. Gauge pigs are not to indicate pipeline cleanliness or whether debris is present in large enough quantities to impair ILI data-gathering capabilities.

Because the line had not been pigged in 20 years and its cleanliness had not been confirmed, the company suggested the operator continue with its original plan of running chemical slugs before ILI. This would reduce the likelihood of sensor lift off during ILI and avoid the risk of degraded data, inspection failure and a costly ILI re-run.

Chemical Cleaning Plan

TDW performed the cleaning operation while the pipeline remained online. A separator at the pig caught the chemical slug and debris.

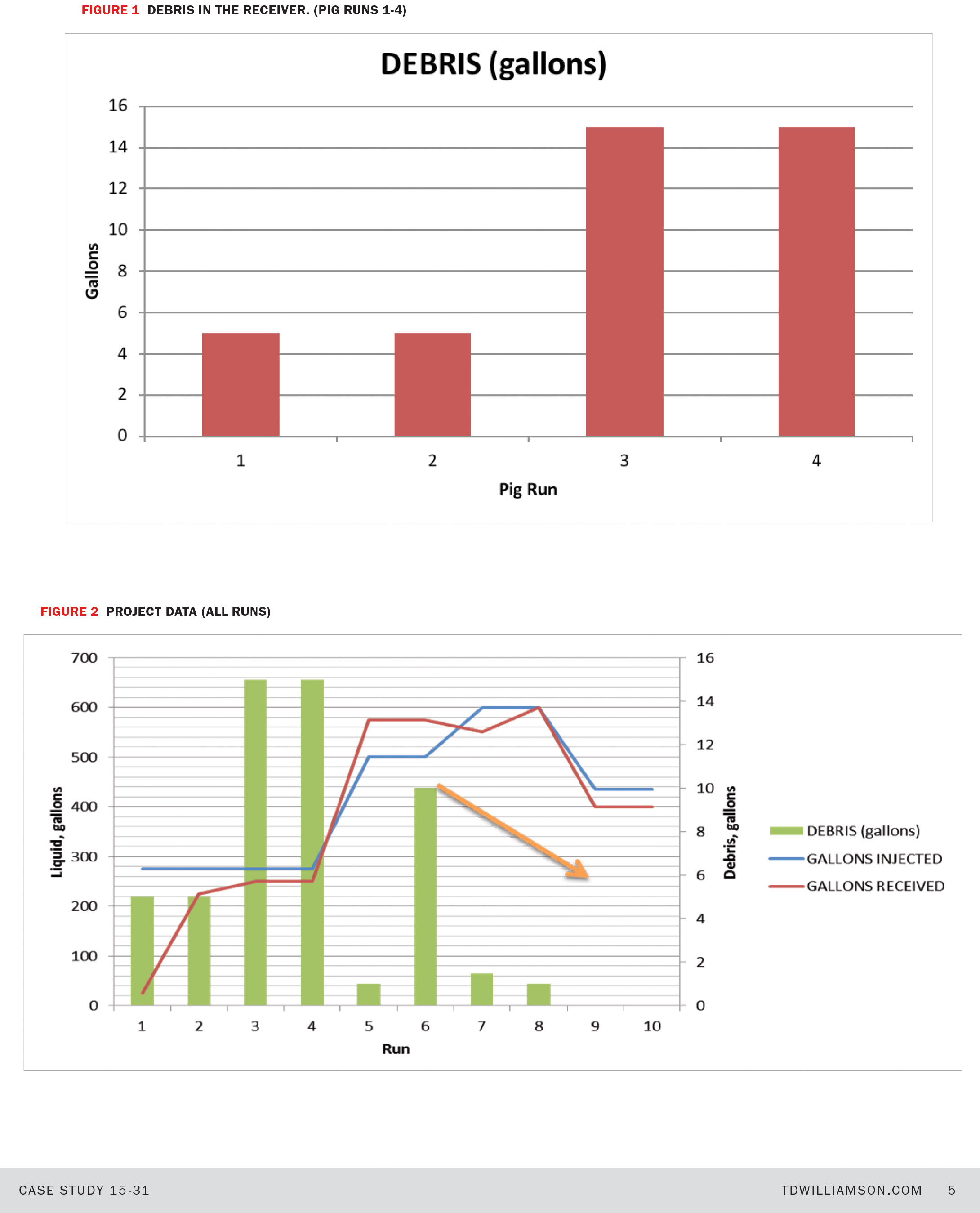

The initial plan called for running four chemical cleaning batches. Each run consisted of two pigs with a chemical solution injected between them, followed by two sweeping pig runs to remove residual chemicals and debris. (Figure 1).

Operations began with low concentration chemical batches composed of about 10% detergent and 90% diesel. Selecting the optimal strength and size of the chemical batch can be challenging. For example, if the solution is too weak, the chemical will not be as effective.

On the other hand, if the size of the chemical batch is too small, the thickness and duration of exposure might be insufficient.

At the end of each run, the level of cleanliness was determined by examining the pigs and analyzing slug and frack tank samples. If any criteria were not met, it meant another cleaning run was required, possibly with an adjustment to the chemical solution.

After the fourth run, results indicated more chemical batches were needed, along with an increase in the concentration of the chemical solution (Figure 2). In the end, it took a total of eight chemical batching runs and two sweeping runs to reach target cleanliness specifications.

Because of the successful pipeline cleaning, the ILI tool was received with little to no debris or liquids, and the run was a success.

Conclusion

With the complexity of technologies employed on a single inspection tool today, the cost of a failed run continues to climb. Failure to achieve first run success can mean additional tool runs, increased downtime and tool recovery or repair, all of which can add considerably to project costs. In this case, the gauge pig run gave the customer a false sense of security that the pipeline was ready for inspection. In fact, the line was not adequately cleaned to enable appropriate sensor contact with the pipe wall and deliver accurate inspection results.

Cleaning the pipeline to a predetermined specification is an effective insurance policy to mitigate the risk of failure due to debris in the pipeline.

As the Pipeline Operators Forum noted, “The quality of inspection results is not only dependent on the quality of inspection methodology used, but to a large extent also relies on the operational conditions of the pipeline during the inspection. A critical parameter to the success of an inspection is the cleanliness of the line, or to be more specific, the cleanliness of the internal surface of the pipeline to be investigated. The consequences of ineffective cleaning are even higher, when the cleaning regime is not specially geared in preparation of inspecting the pipeline using intelligent inline inspection tools.” P&GJ

1Pipeline Operators Forum (2012), Guidance on Achieving ILI First Run Success, p 9

2 Ibid., p 15

Editor’s note: A version of this article was presented at the Pipeline Pigging & Integrity Management Conference, Feb. 8-11, 2016

Author: P.J. Robinson is a graduate of the T.D. Williamson (TDW) Engineering Development program and has been with the company over six years. In his current role he provides technical guidance and expertise to customers and develops engineering reports documenting pigging programs and hydrostatic testing results. Robinson earned a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering from Oklahoma State University

Comments