April 2018, Vol.245, No.4

Features

Diving Deep in the Gulf of Mexico

By Rishi Iyengar, Senior Analyst, PointLogic Energy

After first facing competition from onshore conventional production and then being overshadowed by shale, Gulf of Mexico natural gas production levels has seen its contribution to Lower 48 U.S. total dry production levels fall from 26% in 2001 to just 4% in 2017.

In more recent years, the decline in oil prices since 2015 has had a significant impact on where and how development in the Gulf occurs, with activity in the Gulf increasingly focused on deepwater exploration for crude oil.

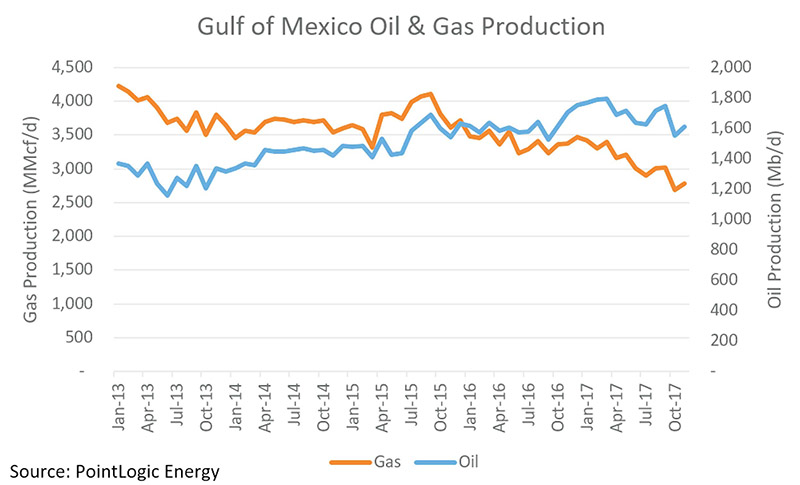

Over the last four years, Gulf of Mexico oil production has been inching upward, while overall gas output has decreased, especially since mid-2015. Gulf gas production has declined by 1.4 Bcf/d since September 2015, and the region’s producers are currently churning out less than 3.0 Bcf/d.

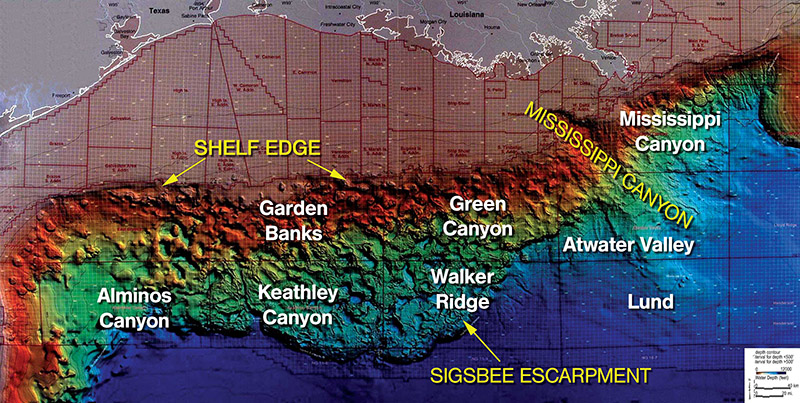

The Gulf of Mexico can be thought of in terms of two distinct production zones: shelf and deepwater. The shelf exists underneath shallower waters closest to the coastline, and extends out quite a bit into the Gulf. Deepwater is everything farther out.

These two regions have very different oil and gas production profiles. First, deepwater reservoirs typically contain far more crude oil per unit of natural gas than those in the shelf. Second, exploration as well as drilling and completion are more costly undertakings in deepwater. Finally, because of the capital-intensive nature of deepwater development, production there is more concentrated among fewer operators. In the deepwater, the top five operators are responsible for nearly 80% of crude oil production, whereas the top five operators in the shelf account for less than 60% of crude production.

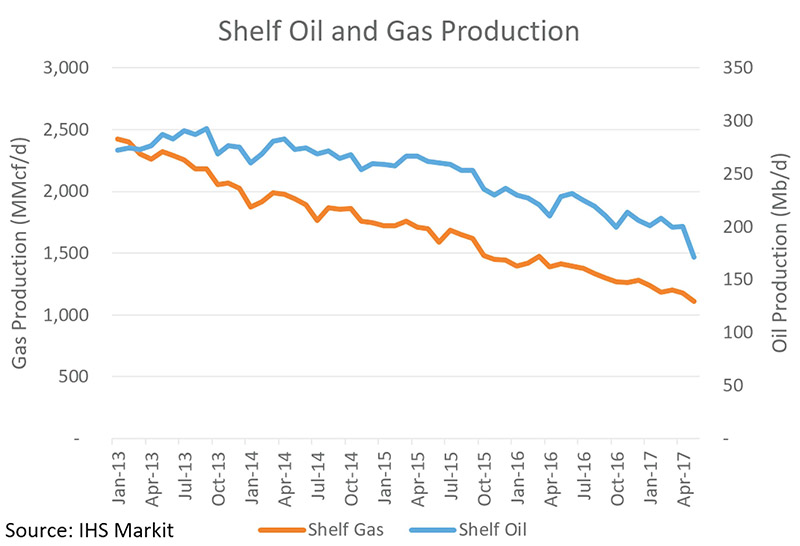

Splitting out Gulf of Mexico production between deepwater and shelf gives a clearer picture of what is happening. As IHS Markit data show, production in the shelf is in clear decline, with gas production decreasing to just over 1.0 Bcf/d currently from nearly 2.5 Bcf/d in January 2013, essentially accounting for all of the loss in overall Gulf gas output over the time period.

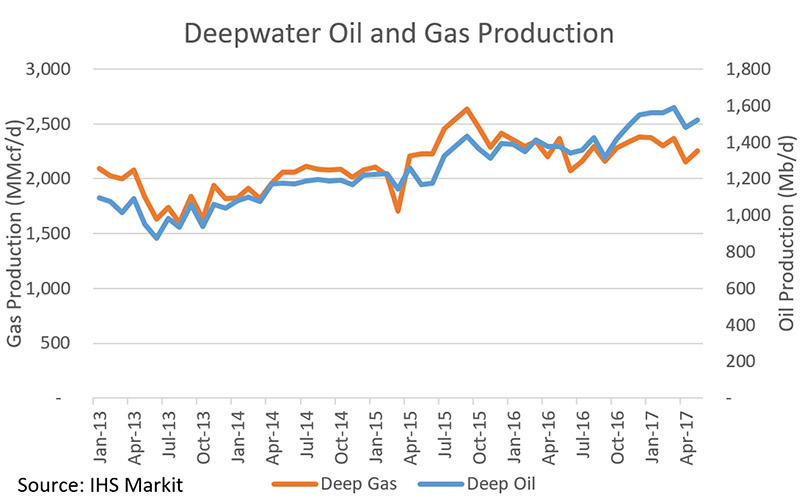

Meanwhile, deepwater oil and gas production has been rising. From May 2013 to May 2017, deepwater oil has gained more than 400,000 bpd, while deepwater gas increased by about 400,000 MMcf/d, helping to defray the declines occurring in the shelf.

But even in the deepwater, additional trends are visible. Deepwater gas production was given a boost in mid-2015, but has not seen growth since then. The bump in gas production is attributable to the development of reservoirs in the Keathley Canyon area, and this development was almost exclusively the work of ExxonMobil, which announced in March 2015 that production had begun on its Hadrian South subsea production system.

Gas production in Keathley Canyon quickly ramped up to just under 400,000 MMcf/d and has stayed fairly close to this level since. But despite the addition of this new gas to the supply mix, and despite continued growth out of Mississippi Canyon primarily driven by Hess and Shell, declines in Garden Banks and other areas have put a damper on deepwater gas production growth.

Splitting deepwater oil production by the same view shows that the primary driver of oil production growth in the deepwater has been a steady increase out of Mississippi Canyon, boosted by the development of the newer and deeper Keathley Canyon and Walker Ridge areas, and supported by minimal declines in other areas. What we are also able to see is that Exxon’s Hadrian South produced only marginal amounts of crude oil, implying that this was a much drier reservoir than the typical deepwater find.

Looking at the trends in oil and gas rig counts for both areas of the Gulf shows that throughout the early 2010’s, gas-directed drilling activity in the shelf had already started to decline because of onshore competition, but oil-directed drilling was still growing in response to elevated crude prices. As soon as crude prices dropped, drilling activity essentially came to a halt in the shelf. Deepwater drilling, while it did also take a hit, has levelled off since 2016.

Gulf producers have slowly adjusted their approach to a lower oil price environment, and their response has been to limit their activity to measured investments into carefully vetted deepwater reservoirs that will provide a large enough resource base for the investment.

All of this suggests that moving forward under current price signals, the only significant development in the Gulf will likely come from new deepwater oil platforms. According to the websites and investor presentations of the top Gulf producers, several new deepwater platforms and other projects are in the works, with announced startup dates within the next 12 months. First, Shell has announced that its Stones Ultra-Deepwater Project is expected to produce 50,000 bpd at full ramp-up. And second, ExxonMobil plans to complete the 3rd and 4th wells in its Julia reservoir in Walker Ridge.

Looking ahead, Hess has completed installation of its 80,000 bpd Stampede platform and expects production to begin during the first half of 2018. BP announced a 2018 startup for its Atlantis Phase 3 project, which will consist of new tie-backs to its existing Atlantis platform. Finally, Chevron is now saying that its 75,000 bpd Big Foot platform will be operational in 2018.

Based purely on the announced capacity additions of major deepwater platforms, one might think that with all of this additional deepwater oil production expected to come online, the associated gas produced could be strong enough to overcome declines in shelf gas production. However, the big downside risk stems from, among other factors, if and when these announced platforms actually see their first barrel of crude.

Not only does the process of reaching an investment decision, constructing and installing a platform, and starting up drilling activity take several years, but there is always the potential for setbacks. Chevron Big Foot was initially expected to start producing at the end of 2015, but part of its structure failed during the installation process, and so now we have its announced 2018 startup. That’s a sizeable chunk of anticipated production that hasn’t shown up yet.

Another trend that puts associated gas at risk is that in the deepwater, the average amount of gas produced per barrel of oil is decreasing. At the beginning of 2013, almost 2.0 MMcf/d of gas was produced for every thousand barrels of oil. That ratio has steadily declined.

Due to competition from lower-risk and more economic onshore shale oil production and the risk of delayed infrastructure development, associated gas production from the deepwater may not be sufficient to overcome the declines in shelf gas. P&GJ

Comments