November 2017, Vol. 244, No. 11

Features

Marcellus-Utica – Planet Earth’s Natural Gas Mecca

Even a casual reader of the North American oil and natural gas industry publications would be well aware of the important role a large swatch of Pennsylvania, West Virginia and eastern Ohio plays in the energy future of not only North America but the world.

Part of that awareness is sparked by the repeated reports in the trade press of industry players and observers all urging fast and steady approval for new infrastructure to process and transport a growing treasure trove of natural gas that appears boundless. Prospects have created the nation’s largest gas producer and potentially the world’s largest-ever basin.

As fall was coming in 2017, it was not clear how much progress on this buildout of historic proportions was being made, despite production projections that are describing a world gas resource that could be double Saudi Arabia’s by the mid-2020s. So to say the stakes are high for the industry, the federal government, the nation’s future economy and world-leading energy standing is a gross understatement.

One positive development came in mid-August when President Trump signed an infrastructure executive order, ostensibly highlighting transportation-related roads, bridges, tunnels and rail, but also clearly aimed at energy with pipelines, transmission lines and various forms of power generation from hydro to nuclear.

“The new federal initiative may not dramatically change the pipeline and other natural gas-related infrastructure review undertaken by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission [FERC], which already appears to be within reach of the [EO’s] target interval for reviews,” wrote analysts at Washington, D.C.-based ClearView Energy Partners LLC, adding that the presidential order would probably help boost electric transmission projects that consistently have languished for longer regulatory review periods.

Clearly, nowhere is the wealth of possibilities the strongest and the energy and economic lobbying the most active, than in the tri-state gas triangle of Ohio, West Virginia and Pennsylvania. A recent U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) report on the Appalachian gas region cited 16 interstate pipeline projects brought online last year with another 25 under development or scheduled for completion this year.

This industry enthusiasm has infected the political leadership in the region as well as demonstrated in August by former Republican presidential hopeful and Ohio Gov. John Kasich, helping dedicate a new natural gas-fired power plant in northeastern Ohio that was spawned by the Marcellus-Utica shale gas boom. Openly shunning nuclear plants seeking subsidies in the midst of low gas-fired generation costs, Kasich boldly declared natural gas as “the future,” while supporting a sustained deregulated environment that brings in more new investors for gas-fired projects.

The governor and others pointed out the new gas-fired, 870-MW Oregon Clean Energy Center was just one of more than 3,000 MW of new or developing gas-fired generation that developer Clean Energy has in its portfolio.

The strength and depth of gas reserves in this part of the nation is exemplified on all parts of the value chain from the growing industrial end-users to the aggressive producers who continue to grind out efficiencies, making it ever more cost-effective to produce natural gas even at under-a-buck (less than $1/Mcf) prices.

For producers, the growth prospects, particularly in the Marcellus have companies such as Pittsburgh-based EQT Energy approaching the shale play from both a producer’s and a midstream operator’s perspective and reaching out to expand as in an $8 billion acquisition earlier in 2017 of Rice Energy Inc.’s acreage and production in Pennsylvania and Ohio, catapulting the Marcellus-focused company into the nation’s largest gas producer, surpassing super-major ExxonMobil.

“This is a world-class inventory at the bottom-of-the-cost-curve in a basin where consolidation drives best-in-class economics,” EQT CEO Steve Schlotterbeck told financial analysts on a conference call in June. Schlotterbeck expects EQT’s cash flows from gas production to double over the next three years, based on the Rice buy that was expected to close before the end of 2017. Mid-2017 gas production of 1.3 Bcf/d was expected to triple to 3.6 Bcf/d after the close. But at the time the CEO still cautioned that the U.S. is entering what he calls the second phase of the shale gas revolution, and as a result, growth must be managed carefully as opposed to following a “grow-as-fast-as-you-can” approach.

Fellow large Marcellus-Utica producer Antero Resources in recent years has touted its technology advances aimed at extending the life of wells and driving up estimated ultimate recovery (EUR) rates, something Antero CEO Paul Rady described several times to analysts during 2017 as part of the major producer’s “advanced completion” process.

“While we are still in the early innings of analyzing the EUR impacts of these advanced completions, we do have a year of production history for wells completed with 1,500 pounds of proppant, and it easily supports the 2 Bcf/1,000-well tight curve,” Rady said in August.

Antero’s bottom line comes from more recent tests using lower and higher proppant loads that caused the company to increase its 2017 guidance range for net production by 3% from 2.25 Bcf/d to 2.3 Bcf/d. Rady said Antero raised the production estimates while keeping its capital budget the same for the year at $1.3 billion.

In providing an engineer’s details on the variables being experimented with by Antero in various pilot well completion tests, Rady emphasizes a step-by-step conservative approach regarding changing proppant volumes and lateral lengths. “We’re ‘inching upward’ rather than ‘jumping out’,” according to the CEO. “We’re making good progress and seeing encouraging results through 2,500-pound proppant volumes.”

The mix of major producers in the Marcellus has stayed pretty much the same, led by companies like Antero, EQT, Range Resources and Consol Energy for the past six years in the face of persistent low gas prices for the most part, according to Sajjad Alam, vice president/senior analyst with Moody’s Investors Service, who has been monitoring the Marcellus-Utica since its emergence a decade ago.

“It’s been hard for players in the Marcellus to exchange some of their gas holdings for something that is more oily,” Alam said. “Since 2011, gas prices have been pretty dismal. These guys have never had a period in which they felt their assets were properly valued. The transactions have been among players who have already got exposure in the basin and trying to consolidate as we saw with EQT and Rice.

“Producers think the slowdown due to low prices has helped bring a balance to supply and demand. With the slowdown the gap between production and infrastructure has narrowed, but looking out to 2019-20, it eventually will begin widening again. There will be a lot more production two years from now and infrastructure needs to get built.”

Unlike the Utica, which is more limited in the near term, Alam sees Marcellus growth potential as world-class, and Pennsylvania itself as the world’s gas center longer term, even in relationship to Saudi reserves.

“In the Middle East there is a lot of associated gas coming out, but forecasts show Marcellus production doubling by 2025, and if you compare that to Saudi Arabia, it is astounding,” Alam said. “If Marcellus goes to 40 Bcf/d by 2025, that is when Saudi Arabia is thinking about taking its gas production to 20 Bcf/d [2025], so that’s half as much. It’s massive and the Marcellus is looking at another Saudi Arabia in the next eight years.”

Globally, Marcellus should be very attractive, he thinks.

“Production rates will continue to improve; I see tremendous growth in the Marcellus the next three to five years,” Alam said. “Longer term as this basin gets more delineated and more infrastructure is built, I think it will stay the top gas-producing U.S. basin for many, many years.”

Alam cautions that the pace of growth will be tied to commodity prices, although he thinks that relatively, Marcellus will remain the leading basin.

This bullishness on the production side has spurred continued reviews by the midstream sector and analysts regarding how the takeaway infrastructure that has come in fits and starts over the last half-dozen years can keep pace. Morningstar Commodity Research is an analytical firm that has kept a steady watch, characterizing gas pipeline infrastructure expansion in the Northeast as the biggest of its kind in the past 50 years.

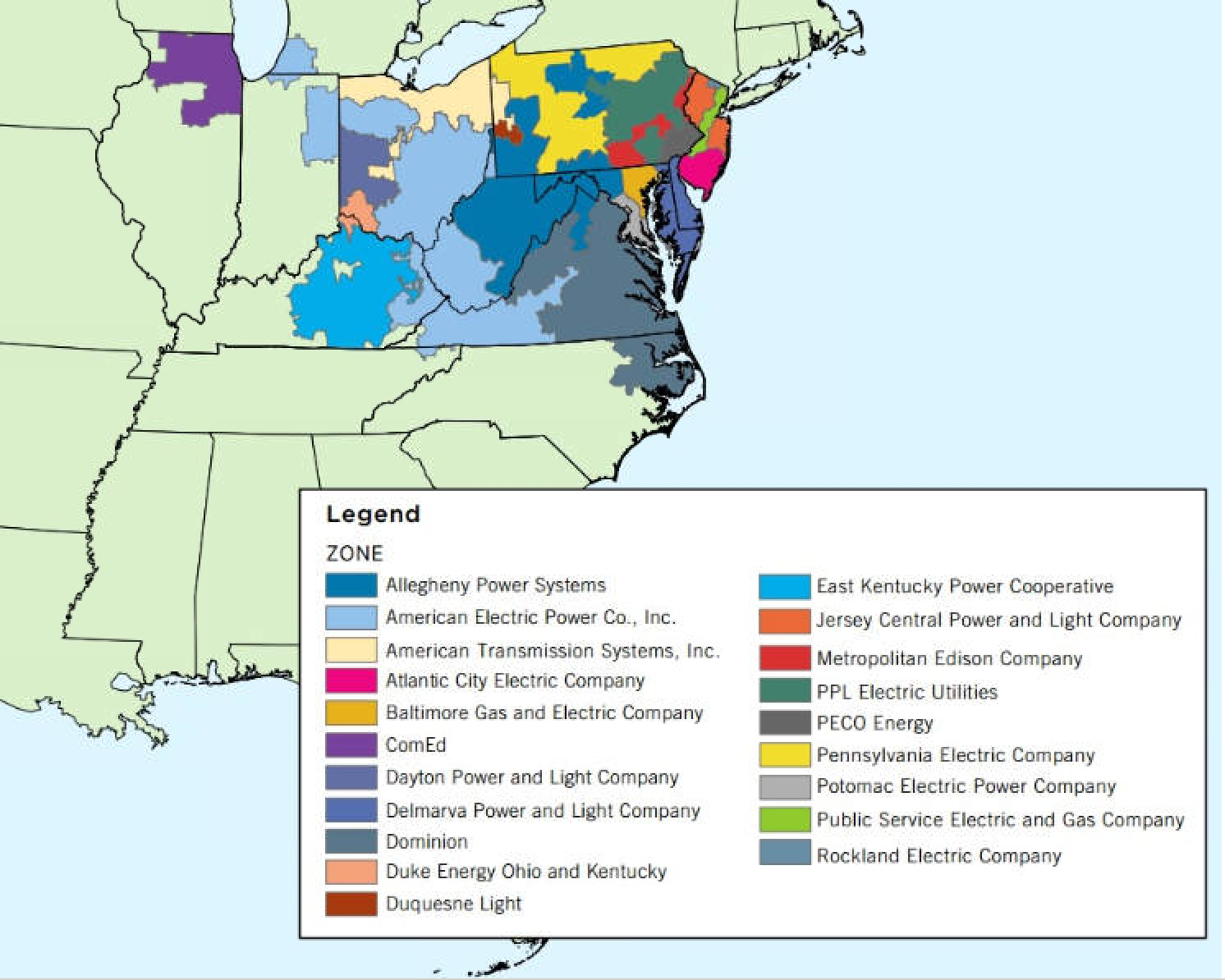

When Morningstar looked intently at the Marcellus infrastructure questions in late 2016, it was bullish on power demand in the PJM grid, and on Cove Point and Gulf Coast LNG export projects, while being bearish on the expected and realized, delays in some major pipeline expansion projects, along with the continued downward pressures on regional winter gas prices. At the end of summer 2017, Morningstar analysts said the same bullishness/bearishness remained valid.

Near-term, Morningstar envisions demand in the mid-Atlantic outpacing supply, but that could be reversed in early 2019 when it sees a “flood” of Marcellus gas coming online and prices being set by marginal cost of Marcellus supply, plus transportation. Eventually, the Gulf Coast LNG export facilities in Texas and Louisiana will own firm pipeline capacity rights of up to 2.1 Bcf/d of Marcellus gas, suggests Morningstar’s last full analysis.

For Morningstar’s analysis, 11 prospective pipelines, totaling over 14 Bcf collectively, were examined with varying start dates from mid-2017 through August 2019. At least 11 major midstream companies are involved in one or more of the pipelines. Destinations for the pipes are far less varied, less than a half-dozen locations, including four each aimed at the Michcon/Dawn and Transco hubs.

From the past three years, there are 18 built or pending pipelines to move Marcellus gas west, 11 going east, and at least four to the Gulf Coast. Morningstar warned the second wave of major pipelines out of the Marcellus has been mostly greenfield. Therefore they have faced a higher risk of cancellations, delays and re-routings.

“Greenfield projects are more expensive and problematic since they involve tougher regulatory and environmental hurdles, and they also need to secure new rights-of-way,” the Morningstar 2016 analysis noted. “Projects crossing the more densely populated Northeast face pushback from locals and political risk at the state level.”

As fall approached and Congress resumed its work for the year in 2017, FERC finally had a quorum again supplied by new Trump administration appointees, and action began to pick up on some of the pending Marcellus infrastructure projects that are a key to the U.S. pipeline sector’s near-term robustness. Partial path service was granted to Transcontinental Gas Pipe Line Co.’s (Transco) Atlantic Sunrise expansion project, inching the 1.7 Dth/d gas pipeline closer to completion as reports swirled around the region that the project was ready to break ground. The authorized portion was to add 400,000 Dth/d of interim service on the Transco mainline from Pennsylvania to Alabama.

At about the same time, a complementary gas processing project from Marathon Petroleum Corp.’s MPLX LP midstream unit, Mark West Energy Partners LP, emerged with construction startup plans for local authorities in southwest Pennsylvania. Called the Harmon Creek Complex (formerly Fox), the revived project includes two cryogenic units along with a de-ethanizer facility and the site eventually could double those facilities. The project is located near another cryogenic processing facility being built by Energy Transfer Partners (ETP) as part of the $1.5 billion Revolution System processing/pipeline project in the region.

And in this dry gas mecca, a study of the Appalachian region that emerged in late summer identified the opportunity for natural gas liquids (NGL) storage and encouraged the industry to pursue it. As part of the region’s interest in developing a petrochemicals industrial base, researchers at the University of West Virginia’s Appalachian Oil/Natural Gas Research Consortium have identified and mapped potential options for the subsurface NGL storage. They have named 50 counties of interest along the Ohio River, stretching from southwest Pennsylvania to the southern end of West Virginia.

Given the enormous economic stakes and the continued bullish projections, there are many eyes – industry, government and investor – closely tracking Marcellus-Utica developments, including at least two major coalitions – Marcellus Shale Coalition (MSC) and the Tri-State Shale Coalition. The tri-state group identified the need for the university study on liquids storage and quickly held a day-long technical meeting on its findings.

“The project represents a critical first step in the development of infrastructure to attract and expand industrial growth in petrochemical and related industries for the region,” the coalition spokesperson said.

In the regulatory arena, MSC has been an active watchdog, urging FERC to hasten review and approval of its members’ critical infrastructure projects, such as the PennEast Pipeline that is expecting federal approvals before the end of 2017. Nevertheless, PennEast has struggled mightily at times in the regulatory review process for the 1.1 Bcf/d, 120-mile pipeline designed to interconnect with Transco in New Jersey.

During this period of FERC inaction, Northeast production continued to increase, as MSC and Pennsylvania sources verify. At mid-year, second-quarter gas production in the Marcellus had increased 3.8% to 1.316 Tcf, according to the state’s Independent Fiscal Office (IFO). Through the first eight months of the year, 2.627 Tcf of gas production was recorded, a 3% jump from the same period in 2016. Observers see the continued growth, albeit slower than historic rates, as a result of gas producers seizing on quick, low-cost production to increase volumes with “drilled-but-uncompleted” (DUC) wells accounting for the bulk of the growth.

With the head of MSC, David Spigelmyer, speaking out loudly at FERC, urging action and the sheer economic momentum pushing more takeaway projects, producers seem to be anticipating a breakthrough in the buildout now that FERC has a quorum. Observers in late 2017 were predicting there would continue to be a ramp-up in Marcellus-Utica production. It also fit the view of analysts like Moody’s Alam.

The companies are just as bullish about the Marcellus-Utica prospects as they were four years ago when they were just beginning to hit the rapid growth button, Alam said.

“From the producers’ perspective, the Marcellus-Utica is viewed as the potential for the production of gas at very low prices,” he said. “Even with continued low oil and gas prices (sub-$2 for gas), they will continue to grow production.”

While federal and state regulatory actions could alter the future one way or another, Alam and others indicate the favorable economics and geology likely will continue to transcend that aspect of the Appalachian future.

For this analyst, Marcellus and Utica have to be separated, but they are both part of an amazing U.S. natural gas story that has yet to fully unfold:

“Utica is newer and the producers are of lower credit quality at this point, so its growth will be more sensitive to natural gas prices,” Alam said. “Due to the liquids part of the Marcellus, the economics are better, particularly in the northeast portion of the Pennsylvania Marcellus from a gas standpoint. It is probably destined to be the cheapest basin in the United States.

“Producers are doing all sorts of things to lower their cost structure. I remember when we started following the Marcellus in 2007-08, producers would tell us they needed $4-5 gas to break even, and costs couldn’t be made any lower. Over the years as there was more familiarity with the geology and fracturing the rocks, they have been vastly able to improve their cost structure. There are producers now breaking even at prices under $2, so costs are still going down, and if the trend stays in place, Marcellus will be highly competitive, relative to any other place in the United States.”

Comments