January 2016, Vol. 243, No. 1

Features

Measuring Methane Emissions: Part of Gas Pipelines’ Future

When examining the growing cottage industry of methane emissions control, it is clear upfront that it is one of the toughest sub-specialties in the emerging conglomerate that makes up the national response to climate change impacts. Researchers, engineers and public-policy wonks must start with the reality that methane coming out of the ground is odorless, invisible and a powerful greenhouse gas (GHG). And that’s the easy part.

Prompted first by operators seeking efficiencies and greater economic value, and more recently by federal government initiatives, the unrelenting effort to curb methane emissions has covered all corners of the industry. The data gathering has spawned widely varying estimates, but one part of the industry – midstream – has drawn a lot of interest in 2015 with the completion in late summer of a comprehensive study by Colorado State University (CSU) engineering researchers. They looked at gathering facilities, pipelines and processing plants nationally, the infrastructure between the wellhead and interstate transportation pipeline systems.

A clear takeaway from the CSU study is that gathering pipelines have a major potential role to play in curbing methane emissions, and they are the most under-researched part of the gas-supply (production-to-burner tip) chain. Researchers measured emissions at 130 gathering facilities and processing plants in 13 states.

Before the recent national effort among the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF), various industry sources and government, methane emissions studies in the gathering-processing sector were almost nonexistent.

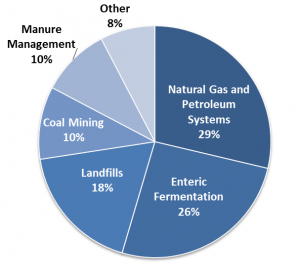

In the EDF-led efforts, the industry was divided into four segments, with exploration/production (E&P), transmission/storage, and distribution being the other three that received studies by third-party nonpartisan research teams. The baseline for methane emissions, an inventory by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, did not break out how much of an estimated 2% increase from 2012-13 came from gathering/processing.

More recently, the CSU engineering researchers pulled out data from the EPA inventory’s E&P emissions that were attributable to gathering compressors, miles of gathering pipelines, and numbers of dehydration systems to count them in the gathering segment as a baseline against the results they collected from measuring actual emissions at these various facilities.

One of the important elements of the study highlighted that gathering needs to be separated out from E&P in studying methane emissions, their sources and potential mitigating actions, according to the principal author of the CSU study, Anthony Marchese, professor of mechanical engineering and director of the CSU engines and energy-conversion laboratory.

Marchese said he doesn’t believe gathering/processing accounts for the bulk of the methane emissions. He said he expects an eventual synthesis of the four national EDF studies will show each segment with about a quarter of the emissions.

“I think they are all similar-sized fractions,” he said, noting that gathering facilities are a pretty large fraction by themselves. His study’s estimates are that about 1,700 gigagrams (Gg) of methane come from 4,600 gathering facilities in the United States.

“That’s a pretty high rate of methane loss,” he said, noting that gathering facilities are separate from the pipelines, which are yet to be comprehensively measured, and separate from processing facilities. (All three – gathering facilities, gathering pipelines and processing plants – make up the gathering/processing segment.) “Most natural gas only flows through one or two gathering facilities between the wellhead to transmission, so that’s a fair amount of gas being lost,” Marchese said.

The earlier EPA inventory defined gathering as part of the production because there are some compressors, dehydration systems and separators on the well site itself that count as part of the “gathering.”

There are also stand-alone gathering facilities with compressors, so the “gathering system,” per se, could be hundreds of miles of pipe collecting gas from hundreds of wells, sending it to a centralized location where there is compression, dehydration and sometimes also treatment for removing carbon dioxide (CO2) and hydrogen sulfide. It is not as large or sophisticated as a processing plant because no natural gas liquids (NGL) are removed. Most have a bank of compressors, dehydration units, and pigging systems for the pipes.

“Even though we consider the gathering pipes part of the system, we did not make pipeline measurements,” said Marchese, in outlining the CSU study that was released late last summer. “In our final estimate, we are just using EPA’s estimate on gathering pipelines in its GHG inventory.”

He said when his researchers dug deeper on the source of the EPA numbers, they discovered that they only come from a handful of gathering pipes made 20 years ago.

“There really needs to be some updating as to the gathering pipelines,” he said, noting EPA estimates point to 445,000 miles of gathering pipeline (all essentially unregulated). The estimates were done in the early 1990s, and Marchese maintains that the gas infrastructure “has changed dramatically” since then, given hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling, placing a lot more wells in much smaller areas, so there could be less miles of gathering pipeline/well now than in the past.

All of the political and regulatory posturing on methane emissions has worn thin with some parts of the industry where real progress has been documented at the wellhead and along the interstate pipelines and storage operations. There continues to be an unquenchable thirst among federal and some state regulators for clearer cut information on where the leaks are occurring and how they can be mitigated.

Organizations such as the American Petroleum Institute (API), Interstate Natural Gas Association of America (INGAA) and the Denver-based Western Energy Alliance (WEA) push back against more regulation, saying emissions are being brought down by ongoing voluntary programs in the industry.

“Methane emissions have fallen 38% since 2005, even as natural gas production soared [upward] by 26%,” said Kathleen Sgamma, WEA vice president, reacting to an Obama administration proposed rule for oil and natural gas producers to curb GHG emissions more. Echoing many others in the industry, Sgamma tries to remind anyone who will listen that the reductions have come as a result of what she calls “industry innovation and voluntary measures.” She said that added federal rules will only add “costly red tape.”

Putting aside the political aspects or perceived political pressures, Marchese said climate change is what has motivated the studies, but he views the motivation for the series of 16 different EDF studies that was coming to conclusion in the final months of 2015 as coming from “the need to truly understand the loss of natural gas through the supply chain, and this is why these studies were supported by industry.”

Gathering pipelines clearly emerge from the CSU study as the potential problem child for the industry, but Marchese said he thinks there are as many opportunities as challenges in assessing this part of the production-to-burner tip journey for natural gas.

“The results of our study suggest that emissions from gathering facilities are higher than industry or regulators would like to see,” Marchese said. “But our experiences from the 20-week field campaign [in which Marchese personally spent five weeks in the field at over 25 facilities] suggest there are many opportunities to reduce emissions.

“The series of EDF studies, when fully synthesized, likely will result in an estimated total loss rate of methane from all natural gas operations of 2% or so. At the 2% methane loss, substitution of diesel and gasoline vehicles with natural gas vehicles would not look too favorable from a GHG emissions standpoint, but substitution of coal power plants still would be favorable at 2% methane loss. That said, I and many industry leaders believe that getting the loss rate down to 1% is a realistic goal.”

A new federal rule related to gathering-system emissions reporting in mid-2015 was taken as a given eventually under the federal EPA GHG reporting program. The CSU study, which had to comply with timing and funding restraints, was unable to include emissions measures from gathering pipelines, Marchese noted. He said the EPA has estimates of these gathering-pipeline emissions being in the area of 178 Gg, and said it is an estimate needing updating, something he expects to happen in upcoming research.

“Prior to our study, gathering was definitely a big gap, and I would say that [our study] closed that gap substantially by performing our national study on gathering facilities,” Marchese said. Nevertheless, he cautions that estimates on gathering pipelines still have a “high uncertainty, and the results on gathering facilities clearly show that [they] represent a substantial source of methane emissions from the entire supply chain.”

Engineers with Gas Technology Institute (GTI) and other R&D organizations suggest that as important as the physical layout of gathering pipelines (and processing) are from a potential emissions standpoint, the contractual relationships of gatherers, processors, producers and pipeline operators are just as crucial to the overall supply chain.

“Both the commercial and regulatory nature of the gas business upstream and downstream of the processing plant is very different,” a Houston-based research-engineer told P&GJ.

R&D organizations such as GTI are developing various diagnostic tools that could be helpful to gatherers, particularly ones in the shale gas plays where there is the possibility of lots of moisture in upstream pipelines. What they call MIC (microbial-induced corrosion) can be mitigated with some new GTI-developed tools, and beyond that, the usual assortment of steel pipeline protection tools will work upstream, such as AC (alternating current) corrosion tools, modeling, field-applied coating training and third-party damage prevention.

GTI officials and others emphasize that the gas in the gathering pipelines is “raw” and may be highly corrosive because it has not yet been treated to remove CO2, C-4s and lighter hydrocarbons, water, or toxics such as H2S, arsenic, mercury (if present) and other toxics. CSU’s Marchese said that upstream gas flowing in the gathering lines often contained volatile organic compounds (VOC) that carry other issues such as ground-level ozone and health impacts, adding additional incentives to find and prevent emissions.

At GTI and other industry research centers, engineers are looking at various small-scale technologies that can capture gas at the wellhead and turn it into a marketable product without having to put it in a pipeline. But some of these researchers point out that for wells producing 10-15 MMcf/d, the cost of the small-scale technologies don’t pencil out. “So, there are still scale issues that haven’t been addressed yet,” one Houston-based researcher said.

While taking issue with some of the extrapolations and loose interpretations of the EDF studies in recent years, officials with America’s Natural Gas Alliance (ANGA, now part of API) emphasize there have been methane-emission reductions made on the production side, and some of the same opportunities exist for the other segments, including gathering/processing.

“The industry is committed to fixing issues where we know they exist,” an ANGA official offered as background on the issue. He further noted that from a public policy standpoint, it is an issue its members are following closely. ANGA is particularly interested in the proposals for voluntary programs that have been surfaced by some parts of the Obama administration.

Industry critics, including EDF, which is working with parts of the industry, argue that voluntary programs will not resolve the emissions issues because the vast majority of the industry has ignored the issue and the programs that some of its counterparts have embraced.

As the EPA was rolling out its methane rules last summer, EDF’s Mark Brownstein, vice president for climate and energy programs, was telling national news media in a series of conference calls that emissions have not been reduced far or fast enough under voluntary efforts. He cited estimates of 7 million tons of methane emissions emitted annually nationwide and said EDF research indicated that total could be twice as large.

“This is why we know that regulations are necessary,” Brownstein emphasized, while conceding that some companies and states already had adopted the same process being considered in the proposed national mandate. “Rules will assure that all in the industry do all that they can.”

Nevertheless, an earlier EPA study showed methane emissions from hydraulically fractured gas wells had declined 79% since 2005, a statistic that the critics don’t emphasize. The industry noted emissions from the total U.S. gas system totaled 157.4 million metric tons of CO2 equivalent (mmtCO2e) in 2013, a 10.7% drop from the 176 mmtCO2e in 2005.

Industry advocates stress methane emissions from field production totaled 47 mmtCO2e in 2013, a 37.7% drop from 2005 levels (75.5 mmtCO2e), and in the distribution segment the decline was 5.9% (35.4 mmtCO2e vs. 33.3 mmtCO2e) between 2005 and 2013.

Over the same period, methane emissions rose by 38.4% in the gas-processing segment (16.4 to 22.7 mmtCO2e). Similarly, despite the declines in recent years, over the same eight-year period, methane emissions from transmission/storage also increased (10.8%) from 49.1 mmtCO2e in 2003 to 54.4 mmtCO2e in 2013.

Noting regulation was not a driver of the CSU study, Marchese said in conducting the gathering/processing study, he and his colleagues saw “fundamental differences” between processing plants (that are already closely regulated) and gathering facilities.

“It is hard to argue that is is because one segment is reporting to the EPA GHG-reporting program and one isn’t,” he said.

Regulatory issues such as leak detection and repair do come into play in gathering facilities, he noted. In processing plants they find them and make repairs, but that’s not the way it is done currently in gathering.

“We didn’t find any major emissions sources at processing plants the way we did at gathering facilities,” Marchese said.

Many of the gathering facilities are unmanned and in regions where dry gas is extracted at 97% methane and thus invisible with no odor, so it is possible to have large emission events being undetected for extended time periods. Marchese said he thinks most of the problems could be resolved with regular maintenance, repair and equipment changes.

Marchese relates his study team’s experience of finding gas pneumatic valve controllers at most gathering facilities, while finding very few pneumatic controllers at processing plants. Most gathering facilities are off the grid in the middle of oilfields without any electricity. They use natural gas to power pneumatic devices for many of their operations, so the possibility of emissions is greater, he said.

“The gas lost at the gathering facility is essentially the same as what’s coming out of the ground,” said Marchese, noting it still has not been treated to take out the bad stuff. “The focus of the studies was methane, but there are other issues, such as ground-level ozone and potential health effects.”

Operations in the gathering part of the business are both a challenge and an opportunity from Marchese’s experience in visiting numerous unmanned facilities around the nation. In the course of the CSU data gathering, many leaks were uncovered with the $100,000 IR (infrared) cameras employed by the research team. Most of them were correctable almost immediately, he said.

Handfuls of employees are assigned to a series of these facilities, which can be spaced 20 miles apart. It is not economic to staff these facilities. Workers are assigned to drive out and check the compressors periodically; they are remote, but there is some sophisticated equipment onsite, according to Marchese. “There are engines that run 24/7.” Right now, he is not sure that there is the same emphasis on finding and repairing leaks in the gathering segment as in others.

The positive side is that when they’re identified, they can be fixed pretty quickly. With or without more federal or state regulations, there is likely to be increasing focus on tightening up this part of the pipeline chain. It is not rocket science as much as a political reality.

INGAA Expresses Serious Concern With EPA Methane Proposal

The Interstate Natural Gas Association, in comments filed Dec. 4 with the Environmental Protection Agency, expressed serious concerns with the agency’s proposal to limit methane from new and modified compressor stations.

“INGAA and its members have a long history of working with a variety of stakeholders on greenhouse gas issues, including methane… Nonetheless, INGAA has serious concerns with the rule proposed by the Environmental Protection Agency,” INGAA said in its comments. “The Proposed Rule would offer little, if any, environmental benefit compared with the more reasonable alternatives offered by INGAA.”

INGAA warned that, if finalized, the rule would impose significant costs and create a real risk for actually increasing the amount of methane released to the atmosphere because in many cases operators would be required to “blow down” pipelines or compressors to complete mandated repairs. INGAA also warned of service disruptions to natural gas customers. These costs and risks of adverse consequences are attributable in large part to the inflexible repair criteria and the lack of workable delay of repair provisions in the proposed rule. INGAA’s comments are available: here.

Written by Richard Nemec, contributing editor and P&GJ’s West Coast correspondent based in Los Angeles. He can be reached at: rnemec@ca.rr.com.

Comments