August 2016, Vol. 243, No. 8

Features

Mexico Energy Reform: The Other Story

Over the past month, two big stories have emerged from Mexico. One is the continued progress in pursuing true constitutional energy reform, with three rounds of auctions on oil fields so far and 30 production contracts awarded in pursuit of a new energy paradigm for Mexico.

The true success of this program remains to be seen, but all indications are there will be a turnaround in the steep decline of oil production in Mexico. Production is down more than 25% from its peak in 2004 and at its lowest since 1986 – 30 years ago – according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

In 2015, the initial auction phase of Round One offered 14 offshore blocks, but only two received bids were deemed adequate and awarded. Since then, the pace and success of the offerings have improved, with 28 out of 30 production contracts awarded. Mexico is on its way to implement the much needed reforms in the oil sector.

The second story is related to air quality. Mexico, for years heavily dependent on electric generation from its own oil, had seen the need to address the crippling air pollution in the country, particularly in and around the high-altitude setting of the capital, Mexico City. At 7,350 feet of elevation and surrounded by mountains on all sides, the city was subject to regular weather events trapping the pollution and severely affecting health and visibility.

Steady improvements in vehicle emissions and other consumption limitations, including reducing electric generation from oil, have improved the overall air quality. However, Mexico City was forced recently to take several actions – including a 40% limit in vehicular traffic – to address a backslide in the improvements to date. While an unusual set of climatic factors may have caused the event, it was a firm reminder of just how tenuous the situation regarding clean air is in the city of over 20 million. And this city is in a country that committed to the global warming directives from COP21 earlier this year.

But the other story (and the reason for this article) is natural gas. Mexico has an abundance, particularly in the south and in the Burgos Basin to the north (Figure 1). By some estimates, shale gas reserves in the country exceed 545 Tcf, fifth in the world, but Mexico is doing little to develop them. This seems counterintuitive.

Meanwhile, the Comisión Federal de Electricidad (CFE) – the state-owned electric utility of Mexico – aims to ramp up new gas-fired power plants from 21 MW in 2014 to almost 56 MW in 2028 to augment or replace existing facilities. This will result in a sharp increase in gas demand in the country (Figure 2). So what’s up with gas development?

Figure 1: Burgos Basin in Mexico. Source: Navigant Consulting.

Figure 2: Mexico’s total natural gas consumption. Source: Navigant’s North America Natural Gas Market Outlook, Spring 2016, Navigant Consulting.

Gas Development

Actually, there’s plenty going on. Shale development in the Eagle Ford fields of Texas, just across the river and a geologic twin to the shale in much of the Burgos Basin, has boomed. Naturally, things have slowed down with the overall downturn in natural gas business activity and commodity prices in the United States, but the Eagle Ford still produces 4.9 Bcf/d and is a fairly easy place to maintain or increase production.

Part of the slowdown is actually rooted 2,000 miles away in the Marcellus and Utica formations in Pennsylvania and surrounding states. The production from there is so abundant that it’s making its way south on reversed mainline pipelines to reach the same markets that the fields in Texas (and Louisiana and offshore) historically served. So where’s the market for Eagle Ford gas? One is certainly in the refineries and processors in Houston as feedstock.

Soon, another will be on the Texas coast, when several LNG export facilities – in addition to Cheniere’s Sabine Pass, which came on stream on Feb. 24 – are constructed and online. Beyond that, though, the market is in Mexico. Such is the abundance of the gas resource base in the United States, which is just starting to export by ship and by pipeline to global markets, including Mexico. It’s already big, and there are going to be shipments of natural gas to Mexico to a greater extent and for a long time into the future, should matters continue to progress as it appears today.

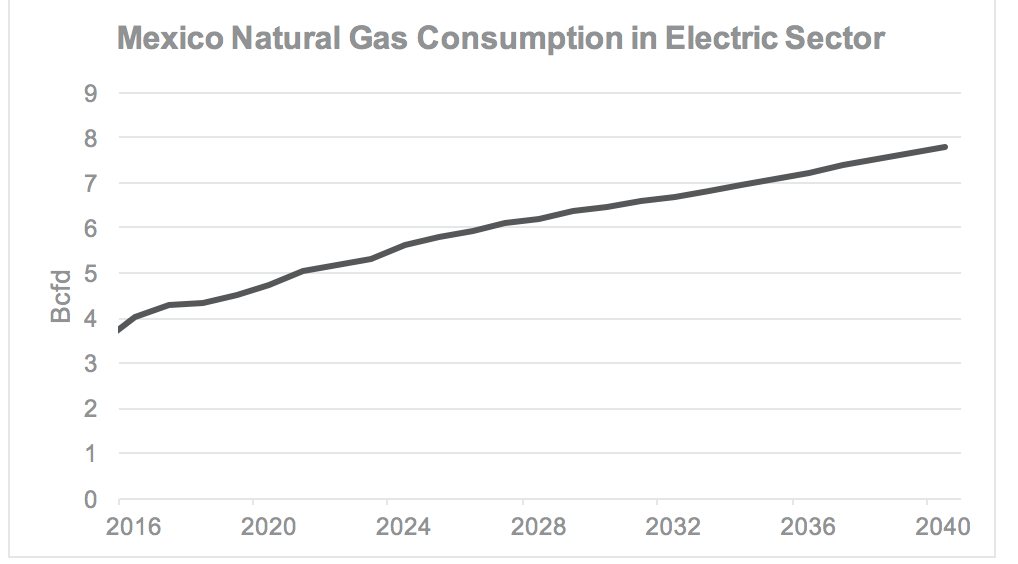

By Navigant’s estimates, the forecast growth (Figure 3) for electric generation gas demand in Mexico will double in the next 25 years. And to achieve this demand growth, you need two things: supply and pipelines.

Figure 3: Mexico natural gas consumption in the electric sector. Source: Navigant’s North America Natural Gas Market Outlook, Spring 2016, Navigant Consulting.

What is interesting as both the United States and Mexico face this new emerging market development is that indigenous gas supply potential in the Burgos Basin in Mexico most certainly exists. Gas resource studies prepared on Mexico indicate its resources rank among the top estimated technically recoverable resources of any country in the world at 545 Tcf.

Domestic Mexican development has been stagnant recently due to factors such as a lack of adequate existing pipeline infrastructure and the extremely small number of shale gas wells (the blueprint for extracting gas is not necessarily the same from field to field, or even within different parts of a field), as well as security concerns in the field. The Burgos Basin lies primarily in the State of Tamaulipas, just south of Texas.

The Zetas and Gulf cartels also have strongholds in Tamaulipas and have become a factor in not only the matter of increasing security concerns, but also in the involvement in the oil and gas business themselves. In fact, some Mexican news reports say the cartels have oil distribution operations that are nearing the scope of Pemex – through illegal taps and hijacked tanker trucks. Edgar Rangel, a commissioner at the National Hydrocarbon Commission in Mexico, has acknowledged these are high-risk areas in which to operate.

Action Items

So what has Mexico decided to do? Mexico has embarked on a plan made up of building domestic natural gas pipelines and importing gas from the U.S. The plan is being pursued on a number of fronts and effectively implemented. It came together seemingly separate from the larger reforms taking place in the country (with some impact from the electric portion of the reforms) and likely could have generally occurred without the reforms.

Three major action items are being carried out simultaneously that affect the Mexican gas industry today: the acquisition of supply, the construction of U.S. natural gas pipelines for delivery to Mexico and the expansion of natural gas pipelines in Mexico.

Mexico has long relied on gas exports from the U.S. to augment its domestic supply. Purchase of this supply has occurred using both long-term and spot contracts. The required credit on the part of CFE (or other purchasing entities) has been adequate to support these sales. Mexican purchasers have long shown confidence in having access to reasonably priced,reliable U.S. supply.

For the most part, this supply is available at or near Henry Hub or the Houston Ship Channel posted prices, which have recently undergone price declines on U.S. gas shale supply abundance. Interestingly, none of these developments required the constitutional reforms in Mexico in order to occur. Instead, they have occurred somewhat like coal-to-gas switching in the U.S. electric generation sector – as a result of the market and the incentive of low prices.

U.S. pipelines built to deliver natural gas to Mexico (Table 1) have crossings that run from as far south as Texas to near the Pacific Ocean in California. Also, the proposed pipelines increase delivery from the U.S. in to Mexico. These pipelines reflect over 10 Bcf/d in delivery capacity, with 7 Bcf/d of that added or to be added since 2014.

For the most part, the pipelines are constructed under long-term (10-15-year), must-pay contracts between the pipeline company in the U.S. and the CFE or another substantial economic entity in Mexico. Credit, like that for the gas purchases, has generally met the requirements of the constructing pipelines, including the tariff requirements of U.S. Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) regulated interstate pipelines.

With the long-term and large-diameter pipeline capacity (and commitments), the going tariff rate for pipelines is estimated at less than $0.25 per dekatherm for deliveries sourced hundreds of miles from the U.S. border. Again, the constitutional reforms did not do anything to boost the building or use of these pipelines. Rather, they expanded domestic Mexican demand and a long-term reliable supply source to the north. Confidence in the continuation of a positive business climate between the U.S. and Mexico has contributed to this scenario.

Table 1: Pipeline projects from U.S. to Mexico. Source: Navigant’s North America Natural Gas Market Outlook, Spring 2016, RBAC, PointLogic.

| Pipeline Project | Capacity (Bcf/d) | Status | In-Service Date |

| San Elizario Crossing | 1.10 | Proposed | January 2017 |

| Presidio Crossing | 1.35 | Proposed | March 2017 |

| Impulsora | 1.12 | Proposed | June 2017 |

| Road Runner | 0.57 | Proposed | April 2017 |

| Sierrita Expansion | 0.31 | Proposed | October 2016 |

| Sierrita | 0.20 | Existing | October 2014 |

| NET Mexico | 2.10 | Existing | December 2014 |

| Tennessee-Rio Bravo | 0.32 | Existing | January 2003 |

| Tennessee-Alamo | 0.22 | Existing | January 1999 |

| Texas Eastern-Hidalgo | 0.32 | Existing | January 1998 |

| KM Mexico-expansion | 0.22 | Existing | June 2014 |

| KM Mexico | 0.43 | Existing | April 2003 |

| KM Border McAllen | 0.30 | Existing | October 2000 |

| North Baja US | 0.51 | Existing | September 2002 |

| SoCalGas Mexico Exp | 0.30 | Existing | January 1998 |

| El Paso Sonora | 0.35 | Existing | January 2001 |

| El Paso Samalayuca | 0.35 | Existing | January 1998 |

| OkTex Del Norte | 0.09 | Existing | January 1998 |

Which brings us to the pipeline capacity across the border in Mexico. There’s no point in building substantial export pipelines in the U.S. if the takeaway capacity can’t be matched south of the border. Mexico has embarked on a large number of projects, like the Los Ramones pipeline, to provide access to and distribution of the supply coming from the north (Table 2).

The long-term vision of these projects is twofold: to bring gas from the U.S. into Mexico and to establish significant infrastructure to allow the distribution of domestic Burgos Basin production, should it develop. This is seemingly a good two-pronged plan. Many of these pipes were built by foreign entities with long experience in building and operating pipelines in Mexico.

Table 2: Proposed natural gas pipeline projects in Mexico.

Source: Navigant North America Natural Gas Market Outlook, Spring 2016.

| Pipeline Project | Capacity (Bcf/d) | Online Date |

| Ojinaga – El Encino Gas Pipeline | 1.35 | March 2017 |

| Gas Pipeline El Encino – La Laguna | 1.50 | March 2017 |

| Gas Pipeline San Isidro-Samalayuca | 1.14 | January 2017 |

| Tuxpan – Tula Gas Pipeline | 0.89 | December 2017 |

| Samalayuca – Sasabe Gas Pipeline | 0.47 | November 2017 |

| Tula – Villa de Reyes Gas Pipeline | 0.89 | January 2018 |

| Villa de Reyes – Aguascalientes –Guadalajara Gas Pipeline | 0.89 | January 2018 |

| La Laguna – Aguascalientes Gas Pipeline | 1.19 | January 2018 |

| Guaymas – El Oro | 0.51 | October 2016 |

| TCPL’s Mazatlan | 0.20 | October 2016 |

| TCPL’s Topolobampo | 0.67 | October 2016 |

| Nueva Era | 0.6 | June 2017 |

The Other Story

Mexico’s growth in natural gas demand is substantial and expected to grow considerably for the foreseeable future. But it occurred in great part outside the realm of the recent constitutional reforms that have been among the big stories in Mexico. This other story, albeit drawing far less attention, is no less impressive. This story has a long and successful history. It also has a bright future ahead with important effects certainly on Mexico, but also on the U.S.

As result of the success of gas supply production in the U.S., it is for the first time in history a net gas exporter – to Canada and Mexico by pipeline and to global markets by ship.

This development is a remarkable about-face in the U.S. and an artifact of the changing role of the U.S. as a valued trading partner of natural gas and LNG – to Mexico and to other countries around the world. And it has very broad future implications – far beyond energy and economics.

Authors: Robert Gibb is an associate director in the Energy practice at Navigant, and brings over 40 years of experience in most aspects of upstream and midstream businesses, in particular in the gas pipeline sector. His most recent work included bringing the first commercial gas storage project to the state of Alaska. Previously, he worked with Marathon Oil Co., Tenneco Inc., El Paso Corp., and as head of Business Development for TransCanada’s major U.S. pipeline and storage projects.

Gordon Pickering is a director at in the Energy Practice at Navigant and has over 30 years of energy consulting, utility industry and oil and gas exploration and production company experience in the natural gas and power industries .He leads the North American Natural Gas and LNG team within its Oil and Gas practice and has been a market leader in identifying gas shale development. He has a strong background in energy pricing, particularly in natural gas and LNG and in the areas of price forecasting and risk management.

Comments