October 2014, Vol. 241, No. 10

Features

Gas Storage: Leading Or Lagging In Growing Marketplace?

The seemingly overnight transformation of the U.S. and North American oil and natural gas gusher into a global supply source has upended many of the long-held assumptions about the American energy industry. This is particularly true for natural gas storage, alternately viewed as an unnecessary anachronism or an indispensable tool for the United States to emerge as a new net energy exporter.

If gas storage is to be a hedge that distinguishes the U.S. natural gas market, the industry and regulators eventually need to resolve whether storage is going to be parceled out by market- or cost-based rates. Traditionally, U.S. pipeline-owned storage has been sold on a cost-based basis; the role of storage in a United States that becomes a gas and oil exporter is still evolving.

In an updated long-range study of North American midstream energy infrastructure needs through 2035, the Interstate Natural Gas Association of America’s (INGAA) Foundation concluded that about $1 billion annually must be invested in new gas, oil and natural gas liquids (NGL) storage. This is a small percentage of the $30 billion a year the study concluded would be needed for all new energy infrastructure over the same period.

“Like pipelines, storage is developed in response to market demand – someone willing to enter a long-term firm contract to backstop the [pipe] development,” said INGAA Washington, DC-based spokesperson Cathy Landry. “Market-based rates are possible, but there is a much higher bar for FERC [Federal Energy Regulatory Commission] to approve them. Even for independent storage for which market-based rates are easier to get, one must assume that the market will reward the long-term commitment of capital.”

That is what executives at NW Natural, the holding company for Oregon’s largest gas utility, have been expecting to happen over the past few years as they struggle to make a profit with their joint venture merchant storage project in Northern California, Gill Ranch.

Despite low seasonal price spreads in 2014, NW Natural’s Chief Operating Officer David Anderson indicated during a quarterly earnings call last August he remained bullish on storage, which he oversees at the Portland-based holding company. With continuing abundant gas supplies in California, “it is a buyers’ market” for storage, said Anderson, noting a $1.2 million net loss for NW’s storage in the second quarter of 2014. “It is still a very low storage market overall.”

Not mincing words, Anderson told financial analysts in late summer 2014 that the 15 Bcf capacity Gill Ranch Storage facility in which it partners with Pacific Gas and Electric Co. continues to struggle, incurring added power costs related to stepped-up injections and $1 million in repair and maintenance charges in 2014.

“It is a difficult storage market right now,” Anderson told the quarterly earning conference call audience. “We’re trying to make the best of it. Most of our contracts are short-term in nature, reflecting the very low prices.”

Reassessing convention?

Even with the extreme draw on natural gas storage in the most recent winter (2013-14), gas industry insiders outline a “conventional wisdom” that sees the ongoing shale revolution as diminishing incentives to develop new storage in North America. Much of the seasonal volatility has been wrung out of the market, they say, cutting down on the opportunities for market players to arbitrage storage.

However, some question whether the experience of the past winter will cause a reassessment of this conventional thinking.

One veteran who doesn’t agree that robust shale supplies have made storage obsolete is John Hopper, co-founder, board member and former president/CEO of Peregrine Midstream Partners and earlier Falcon Gas Storage Co. Hopper thinks the storage business is still “all about fundamentals” – price volatility and forward curves for natural gas prices and price differentials. He admits those differentials have compressed with the shale boom.

“It is because the market perceives we have all the gas we need that volatility has been dampened, along with the differential compression, and neither of these situations provides a market for gas storage,” he says.

A serial entrepreneur by his own definition who at the time he talked to P&GJ was moving on to other opportunities outside of Peregrine, Hopper believes that over the long haul demand growth in response to continuing low gas prices will change the perception that today lingers in the market.

“I think there is a surprise in store for the marketplace but when exactly that it is going to happen is hard to say. I would say sometime in the next couple of years [2015-17],” Hopper says. “That will be good for storage when it does happen; I don’t think it is ‘if’ but ‘when’ it is going to happen.”

In early summer Hopper was troubled by forward winter 2014-15 gas prices that were not much different than the summer injection season prices. It was as if the market players had amnesia regarding the bitter cold December-February period just passed when average prices were $8-$9/Mcf, and in some instances, $40 prices at Opal Hub last February, he said. Even California, which has large amounts of gas storage, was running short of gas supplies this past winter.

“It is a mystery to me why the market [for gas storage] coming out of this past winter seems to have completely forgotten about what just happened,” says Hopper, noting that last winter the United States had more than 3.8 Tcf of gas in storage. This winter the forecast is only 3.4 Tcf by comparison, and in late summer all indicators pointed to that total being reached.

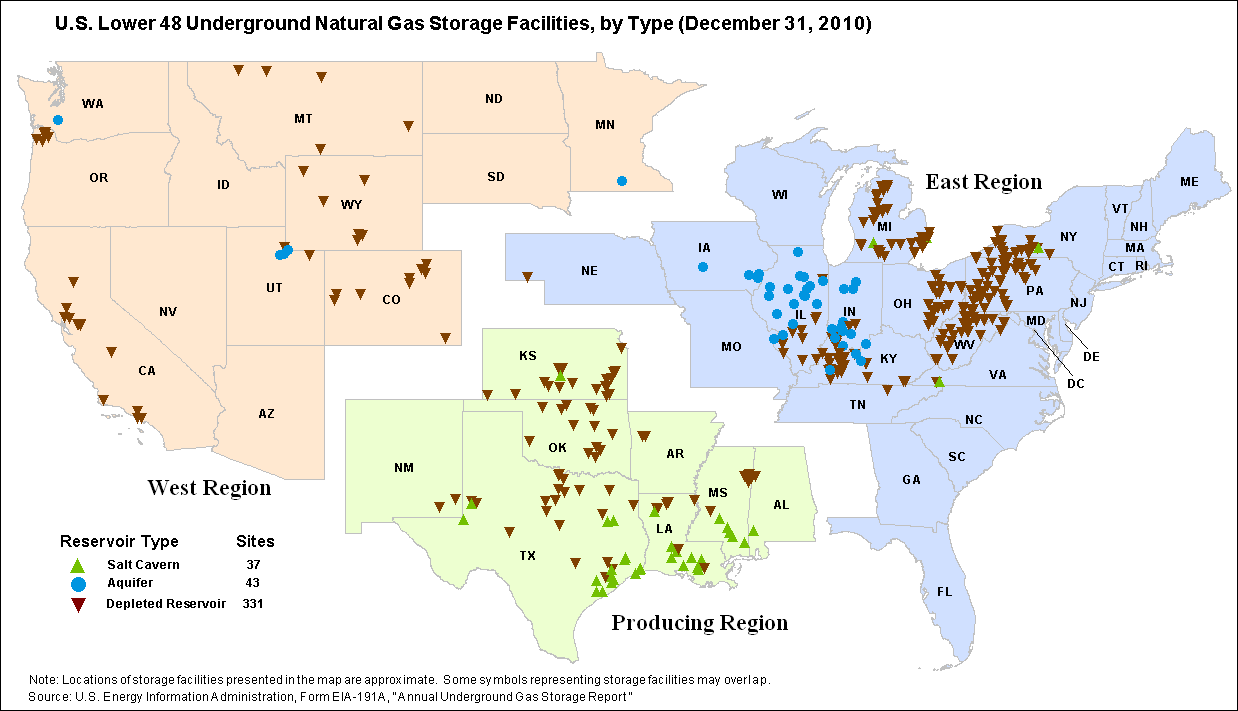

Although Hopper may not agree, Jennifer Fordham, vice president for markets at the producers’ Natural Gas Supply Association (NGSA), said gas storage helps balance the market daily and seasonally. In the United States, the combination of robust supplies, diversity of storage options and geographical diversity of both allows the natural gas markets in North America to respond to a wide variety of customer needs.

“I’m bullish on natural gas and its ability to be a driver in the American economy,” Fordham said. “Storage is what allows the levels of reliability and diversity that the United States enjoys with natural gas. This is not the same industry we had 15 years ago.”

‘Weather Still Rules’

A national analyst with Platts’ BENTEK Energy unit, Jack Weixel, thinks the main lesson from the most recent winter is that “weather still rules all,” citing the second-coldest winters ever in the Midwest and Texas, and the sixth-coldest in the Northeast. Weixel, in the early part of summer, was expecting the 2014 injection season to be another lesson in accelerating refilling storage in the midst of shifting dynamics toward increased use of gas for power generation.

“With just a little bit of weather, storage is going to be a lot more sensitive to larger swings now that the market has tightened [with supply-demand closer together],” Weixel told a Houston energy conference in June.

While drawing short of calling gas demand volatile, Weixel says there is much more baseload gas demand than most people realize.

“That can lead to some volatility on price although power generators don’t want to hear that,” he says. “That’s reality. So if you don’t want to hedge your bets, storage can be a pretty good option, particularly for end-users [of natural gas].”

Like NGSA’s Fordham, Weixel says he can be classified as bullish on storage, but only in a long-term sense. He expects the summer of 2015 to be a breakthrough. “We have 17 GW of coal [generation] retirements upcoming, meaning more natural gas for baseload.”

Weixel anticipates this will pressure summer prices next year, but it will start to affect winter prices for 2015-16, too, because the summer loads will weigh on storage levels, and this eventually will pressure the winter prices. Acknowledging there is going to be more of a national basis for storage, Weixel agrees the shale revolution and the LNG exports in combination will drive up the value of storage and add pressure for more to be built in the United States.

“Producers don’t need storage, but as they produce more, more consumers rush into the market, and these consumers happen to be LNG guys,” he says. “Most LNG facilities are in the Southeast/Gulf of Mexico region, and all the production now is to the North/Northeast, so when it gets cold in New England, all that gas stays up there and the LNG still has to go out, so I would think you would have to have some storage.”

In addition to exports and continued supply growth, what will really raise the value of storage are U.S. regional issues, says Fordham. Storage can be a valuable tool in meeting some of the regional and seasonal demand requirements for natural gas, she says, adding that domestic supply growth remains a factor, too.

“Storage is just one of several aspects needed in a diverse, flexible market. Perhaps the growth in power demand really stems from supply and market changes, and the overall diversity that storage helps provide in the market,” says Fordham, adding that the geographic diversity of shale supplies has been a “huge” factor for the market.

She thinks the regional influence can be seen over the past 10 years with the development of high-deliverability, multi-cycling (HDMC) storage to replace typical reservoir storage, which some industry players still prefer, such as Peregrine’s Hopper.

Fordham calls the HDMC “a response to regional market conditions where there is a hedging power-generation requirement, and salt-dome facilities can be cycled 14 times a year, although they are typically smaller in capacity [than reservoir storage].”

Hopper says he is still biased for reservoir storage that is “multi-turn (cycle)” because that is what he has continued to develop, including Peregrine’s Ryckman Creek Rockies Storage project in southwestern Wyoming. Hopper contends the market is looking for reservoir storage that can be turned at least three times annually, but he is also aware of the role of gas prices and government in charting the future of gas storage in the newly formed U.S. energy landscape.

“Prices are always going to be a driver,” Hopper says. “Historically, we’ve [his former company, Peregrine] looked at what, if any, correlation there is between gas prices and storage spreads that translates into value for storage and volatility. There is some correlation, but it is clear it costs less to store gas at low prices than it does at high prices. Your carrying cost is going to be lower in a $4-5 market than an $8-10 market, and I don’t expect to see $8 or $10 forward curve prices ever again, even though we saw prices well north of that last winter.

Government’s Role

“The ideal scenario for us [Peregrine] is $3 gas in the off-peak and $6 in the on-peak,” Hopper says. “That would be just fine for us, but we’re just not seeing those types of seasonal spreads right now [in mid-2014].”

And what about the government’s role? Hopper and others interviewed by P&GJ are cautious and a bit ambivalent on this question.

“An interesting wild card” is how Hopper sees government’s future role on storage. He sees FERC as trying to be a “referee” between gas-fired power generators and gas suppliers.

Bentek’s Weixel says his fellow analysts haven’t fully studied the role of government or the larger impact of carbon emission reduction goals from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). He is confident there are enough coal plants scheduled to retire by 2020 to get 18-20% added greenhouse gas emissions reductions relative to the nation reaching the EPA goal of moving overall emissions back to 2005 levels. For this, storage would have a role to play, he says.

To the extent that carbon reductions in the power sector drive the development of more gas-fired generation, “It is like LNG exports in terms of its impact on storage,” Weixel said. “It increases the baseload demand, and that increases the need for storage.”

To Weixel, there are no clear-cut physical or geographic limitations on storage; the limits mostly are economic. But he thinks there is a dearth of leaders within the U.S. energy industry really pushing added storage. In his industry presentation earlier in 2014, he said that through 2019, there is about 151 Bcf of new storage capacity proposed, less than 3% of existing U.S. capacity.

“The capacities that people are planning for future storage are completely inadequate,” he says, citing the Southeast as an example in which current plans add up to 1 Bcf/d of added capacity through 2018.

Nationally, by early August, the U.S. storage system in less than three months pulled in 1.3 Tcf at a historic pace to help refill reservoirs that gave up a record 3 Tcf during the December-February period, according to Energy Ventures Analysis’ Stephen Thumb. “Contributing to this record storage outcome is a steady increase in domestic gas production – up sequentially a little more than 1 Bcf/d in the 90 days since May 1 [2014],” Thumb reported in August.

Both Fordham and Weixel are unconcerned about the continuing regional shifts in production and what this means for demand increases and necessary storage development. But Weixel looks for demand factors to “shake out” from now through 2018.

“Demand is going to increase, the market will tighten, and there is justification for looking at [more] storage,” he says matter-of-factly. Generally, Fordham adds that “This is a really great time for natural gas investments.” Neither would say whether given this bullish outlook, new storage will lead or lag in the market.

Richard Nemec is Los Angeles-based correspondent for P&GJ. He can be reached at: rnemec@ca.rr.com.

Comments