June 2014, Vol. 241, No. 6

Features

Operators See Bumpy Road Ahead, Despite $640 Billion Demand For Midstream Infrastructure

Faced with a study projecting that the pipeline industry will need an average of $30 billion per year worth of new infrastructure to satisfy oil, gas and liquids transportation needs between 2014 and 2035, pipeline operators foresee struggle and risk as well as opportunity.

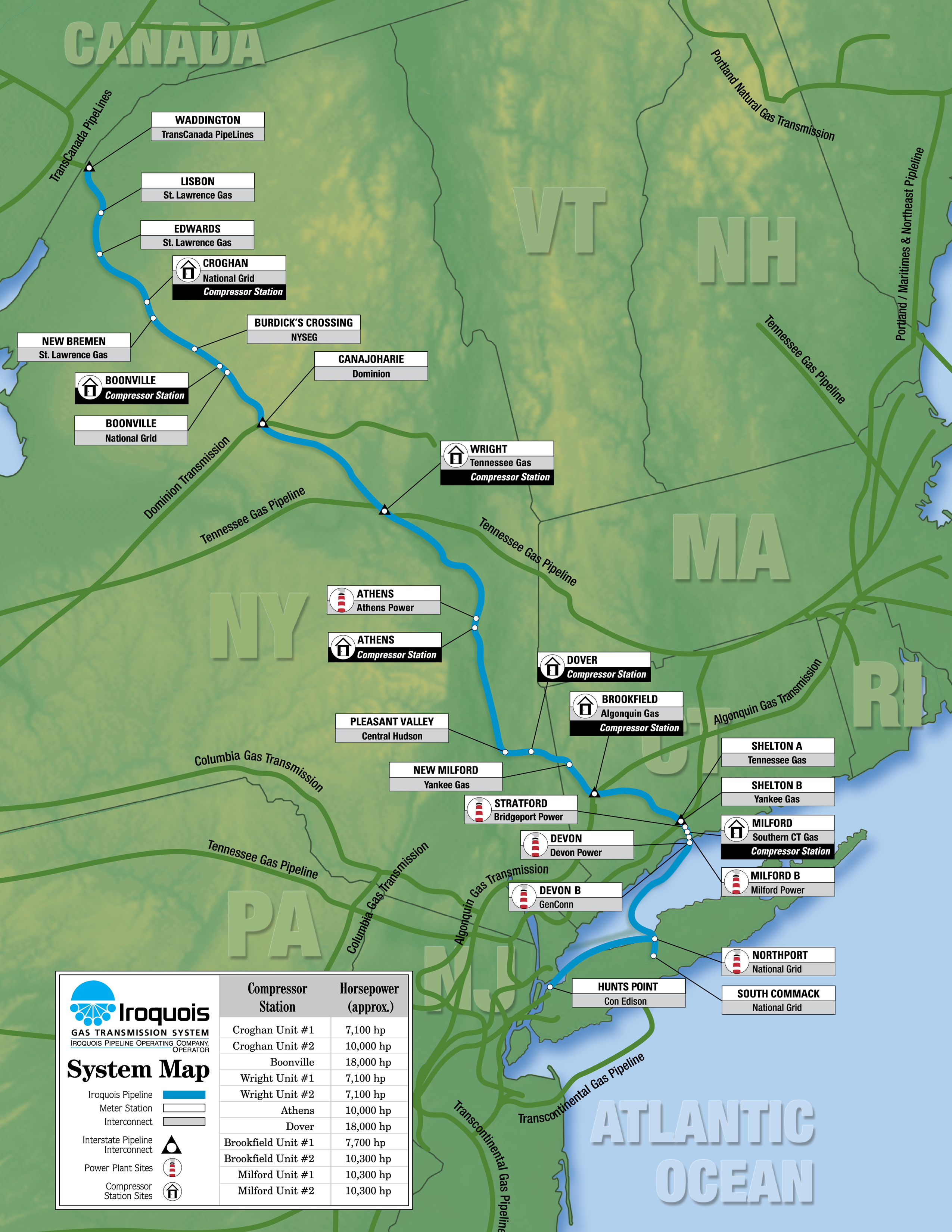

Jeff Bruner, president of the Connecticut-based Iroquois Pipeline Operating Company, said of the study, “It assumes that if you have supply and you have demand, the pipeline will get built. . . . For people in the Northeast that’s easier said than done.”

Guy Buckley, chief development officer for Spectra Energy, said permitting processes and more pre-construction work limit how fast operators can respond. “There’s more species, there’s more people you’ve got to touch, there’s more outreach, there’s more opposition,” he said. “You guys are sitting there saying ‘let’s start building it; if you want us to meet the numbers, let’s get it in the ground.’ Well, that’s all got to come together.”

Stan Chapman, executive vice president and COO of Columbia Pipeline Group, compared the construction frenzy to the California Gold Rush. After 150 years of building infrastructure to move energy from south to north, he said the industry would now take the next decade to reverse the flow.

The executives spoke to the spring meeting of the Interstate Natural Gas Association of America Foundation, held April 2-4 in Austin, TX. Their comments responded to a study by ICF International, “North America Midstream Infrastructure through 2035: Capitalizing on Our Energy Abundance,” commissioned by the Foundation. (For P&GJ’s initial reporting on the ICF study’s findings, see May 2014 issue, Vol. 241 No. 5, page 30, or http://pipelineandgasjournal.com/study-estimates-us-and-canadian-midstream-investments-30-billion-year.)

The ICF study concurs with other recent analysis in finding a large and growing need for gathering systems in and around new production areas and transmission pipelines to move gas from the Atlantic midcontinent and Marcellus to the urban centers of the Northeast. Gas, crude and diluted bitumen await transmission lines to move resources out of Western Canada, and an expanding American petrochemical industry will require feedstock. Planned LNG export facilities will also require hundreds of miles of pipeline construction.

Combining gas, oil, and natural gas liquids needs, the study predicted demand for 2,230 miles of new transmission infrastructure and 21,800 miles of gathering lines per year. Total investment required came to $640 billion 2014-2035, up from $200 billion estimated for the 2012-2035 period based on a previous Foundation study.

Not all that investment would go to new builds. Chapman said pipeline companies will also spend time and money managing line reversals, conversions to transport a different payload and even abandonments of existing lines.

“Pipelines are seeing a reduction in their long-haul transportation throughput,” Chapman explained. “Gas costs are cheaper in Pennsylvania than they are off the Gulf Coast of Louisiana and one would incur lower variable costs to move that gas to market [in the Northeast] seeing as how it’s in the market area already. That’s requiring pipelines to basically reinvent themselves.”

Costs Per Inch-Mile Up, Target Market Wary

With increased demand for natural gas for power generation, more people moving from oil to gas for heating, and large volumes of Marcellus gas available close by, Northeast markets such as Boston, New York and New England are excellent prospects economically. But construction in that region requires special consideration.

Referencing the difficulty Iroquois had in constructing a pipeline through the urban Northeast in the ’90s, Bruner said siting and permitting in the region has always been hard but is getting even harder. “Now you’re starting to see not just the NIMBY group, which is what we were mainly faced with, but the anti-fracking groups, the hard-core environmentalists. To the extent that even if you’re trying to build a pipeline across New York to carry gas from Pennsylvania, they’re still opposed to it because it’s that nasty fracked gas.”

Bruner said some people in the area object to the idea of investing in new pipelines at all, regardless of where they are built or how the products they carry are produced, since the long life of a pipeline implies a long timeline of continued fossil fuel use and carbon emissions. “Because [new pipelines] last more than 10 years, [and activists think] we need to get off natural gas in 10 years. Otherwise we’re not going to meet these protocols, and we’re not going to be where we need to be with respect to the president’s program for clean energy and clean air.”

Nor were environmental concerns the only stumbling block Bruner expected for new construction. “The eminent domain issue, particularly in the Northeast, is huge. They look at that as kind of going back to the king taking their property. It makes siting anything up there very challenging.”

The ICF study identified increasing costs per pipeline inch-mile, estimating a standard rate of $155,000 throughout North America and providing multipliers for areas where difficulties were unusually high. The northeastern metropolitan multiplier suggested pipelines there would cost 1.46 times the standard rate. Bruner calculated the rate would predict an expected cost of $5.5 million per mile for a 24-inch transmission line in the region.

“That’s a lot, but I would argue that as you’re building pipeline into some of these big infrastructure, big market areas, New York [and] some of the very populated areas, that’s very low. That misses the mark by maybe two to four times,” Bruner said. In addition to delays, siting, directional drills and specialty construction methods would all add significantly to the cost. He mentioned in particular stove pipe construction, in which one joint of pipe is installed at a time and welding, weld inspection and coating are done in the open trench.

Comparing the study’s prediction to construction costs for Spectra’s newly built New Jersey-New York expansion line terminating in Manhattan, Buckley said, “I can tell you the multiplier factor was not correct — either that or the decimal point was one off. It’s incredible the opposition and the effort that you have to go through to do it.”

Still, Bruner emphasized that the Northeast offers opportunities as real as the risks. “You’ve got a huge amount of gas and one of the best markets in the world. There are some big home runs to be hit there. But those home runs are going to be few and far between.”

Capital, Profit And Permitting More Complicated

A cross-regional issue is in funding and profiting from projects in a marketplace where many old norms have shifted. “It used to be LDCs signing contracts, now it’s the producers,” Bruner said. “We’re not talking about the ExxonMobils and Shells of the world. We’re talking about smaller producers.” With their available capital tied up in exploration and production, “They don’t have great balance sheets. So when you talk about signing up these long-term contracts, it presents a lot more risk to the pipeline that they’re going to collect their rates of return.”

Buckley said Spectra’s customers want more speed and certainty. “The market time has compressed. Customers want an answer that you’re going to build something today. They want you to sign a contract and say what it’s going to cost, when you’re going to be in, and get it going.”

Meanwhile, Buckley said, pipeline permitting and planning has expanded. “Basically, the process has gotten longer. That puts a lot of risk and tension on the process.” For a FERC-regulated gas transmission line, he expected timelines in the three- to four-year range. For oil pipelines needing permitting from individual states, he couldn’t suggest any timeline.

Contributing to the lengthening schedules was the workforce crunch hitting regulators. “One of the concerns I have is, are the resources going to be there, not just for us in the industry, but are there going to be enough resources available in the agencies?” Buckley asked. “This isn’t just FERC and the federal agencies. You’ve got to touch a bunch of states.”

One Foundation proposal suggested a pilot program in which companies could pay to supplement the workforce of public agencies where their projects are being reviewed, but most members thought it was unfeasible.

Despite the challenges he saw to the industry’s expansion, Buckley said the benefits of development are broader than many realize.

“This is not just about us making money in our industry, it’s not just about is this the right thing for our businesses. It actually is a really good thing for the economy,” Buckley said. For instance, he said Spectra’s New Jersey-New York expansion line had dropped the premium paid for natural gas in New York City from 64% over Pennsylvania prices to 13%.

“That’s not just good for our business and good for you guys. That saves a lot of money for a lot of people,” Buckley said, referencing an in-house study estimating the city would save $700 million per year due to the lower gas costs. “That’s money that’s put back in the economy, in people’s pockets. It’s a great way to drive economic renewal and economic growth. What we’re doing actually serves a pretty good purpose.”

New research

The INGAA Foundation spring planning and studies meeting holds discussions to determine where it will next focus its research efforts. The most popular proposal at April’s meeting was a data-gathering effort targeting the AERMOD atmospheric dispersion model. The model is used to measure NO-2 ground level concentrations for reciprocating equipment. Based on field observations and a previous study, the INGAA Foundation environmental, health and safety committee believes the model significantly overestimates levels of NO-2. Foundation members agreed to support a project to gather a large set of actual field data in order to prove the model’s inaccuracy and convince regulatory bodies to improve it. The data gathering is expected to take several years, beginning in 2015, and will combine the efforts of pipeline operators, OEMs and service companies.

Second-ranked on the priority list is an effort to develop a third-party certification program for pipeline inspectors which dovetails with a report released May 9 by the Department of Transportation calling out the lack of training criteria for intrastate pipeline inspectors.

Comments