April 2014, Vol. 241 No. 4

Features

Energy Struggles Between Russia, Ukraine Feed Conflict

Just how serious the Ukraine-Russia situation is and whether it will threaten global security and stability is still unknown. However, the contribution of energy politics to the clash is well-established. It was on the minds of world energy leaders who met at the annual IHS-CERA Conference in Houston March 3-7, shortly after pro-Russian forces occupied strategic areas of Crimea.

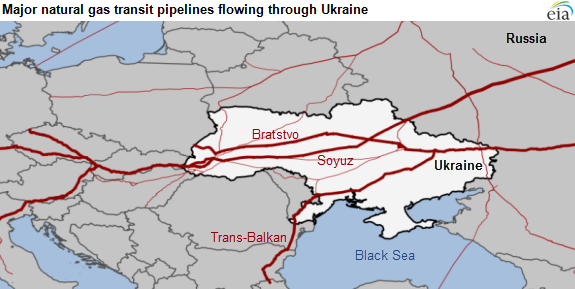

Ukraine’s proximity to Russia makes it an important corridor for natural gas transit, through which Russian gas volumes flow to Austria, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Moldova, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Turkey. Overall, Europe got approximately 30% of its natural gas from Russia last year, according to Michael Stoppard, Managing Director, of IHS CERA’s Energy Research Council.

Meanwhile, despite the Nordstream and other “bypass pipelines,” 50% of Russia’s gas exports to the West still travel through Ukraine. Russia supplies 50 Bcm annually to Ukraine itself.

Despite the interreliance, conflict between the two is nothing new. Russia has long accused its neighbor of siphoning off supplies meant for European customers to meet its own needs.

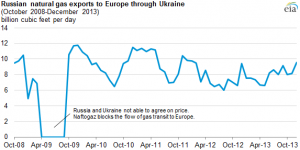

In the past, disputes between Russia and Ukraine over natural gas supplies, prices, and debts have twice resulted in interruptions to Russia’s natural gas exports through Ukraine, with the latest one occurring in 2009. As of press time, gas was apparently flowing, notwithstanding the latest upset.

Trouble between the two countries was brewing even before the formation of Kiev’s new pro-Western government. Ukraine reportedly has a $1.5 billion outstanding debt to Russia for gas delivered late last year, part of a “penurious state of public finance” in Ukraine, as described by Matthew Sagers, senior director for Russia and Caspian Energy for IHS.

A meeting on Ukraine’s gas debt between Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev and Gazprom Management Committee Chairman Alexey Miller on March 4 resulted in a decision to discontinue gas price discounts for the Ukraine beginning in this month. At the meeting, Miller reported that Ukraine hadn’t settled the gas debt of last year and would not be able to pay in full for recent gas deliveries.

The following is taken from a transcript of the discussion between the two officials as posted to the Gazprom website as of March 5:

Medvedev: What is the situation with Ukraine? Do we have any new issues or everything stands where it was?

Miller: Ukraine hasn’t settled the gas debt of the last year and today the country’s outstanding debt for current gas supplies is increasing. Gazprom hasn’t received any payments for the gas supplied in January, and our Ukrainian partners informed us yesterday that they would not be able to pay in full for the gas supplied in February.

At the end of the last year it was agreed that Gazprom would give Ukraine a discount price for gas, provided that Ukraine would ultimately clear the debts accumulated over the last year and would pay in full for current gas supplies. Unfortunately, I have to state that Ukraine hasn’t paid off for the gas supplied last year.

Medvedev: How much in total have they managed to repay?

Miller: Speaking of the last year’s indebtedness, they have repaid US$1.3 billion.

Medvedev: Which means 50% of the debt?

Miller: A little less than 50%. The total gas indebtedness of Ukraine makes up US$1.529 billion now. Given that Ukraine is not fulfilling its obligations or complying with the agreements reached when signing the contractual addendum providing a gas discount, Gazprom resolved to remove the discount starting from this April.

Medvedev: I see. The one who fails to pay for the supplied goods should be aware that it is fraught with adverse consequences, including those related to the revocation of previously reached agreements on beneficial terms of supplies. Nevertheless, what is your opinion of the measures that should be taken to have this debt repaid?

Miller: Of course, the amount of Ukraine’s debt to Gazprom is considerable. The last year’s debt was reflected in Gazprom’s budget for this year, and this amount is included into our investment program. Indeed, it is a big sum of money. Therefore, the easiest and efficient way for Gazprom would be to provide Ukraine with a loan in the amount of US$2 or 3 billion so that it could settle its indebtedness accrued from the last year and pay for current gas supplies.

Medvedev: It’s no secret that the 50% they paid came from the sovereign loan we had given them. This is a possible way of resolving this problem. I will entrust the Ministry of Finance to consider all the possibilities and obstacles as well as all the contradictions related to the extremely low credit rating of Ukraine now, in addition to other aspects of the Russian-Ukrainian cooperation in this area. Firstly, Gazprom anyway should insist on the full coverage of the debt owed by the Ukrainian partner. Secondly, your decision to terminate the beneficial terms of supplies looks completely justified.

Western European Gas Needs Inform Diplomacy

Liberalized gas trade in Europe’s Third Energy Package legislation, which moves the region to a more American-style market with non-oil-linked spot prices for gas and unbundling to allow third-party access to pipelines, has affected the trade relationship between Russia and the European Union. According to IHS Senior Director of Russian and Caspian Energy Thane Gustafson, before the current conflict, the two sides were making progress.

Now much of that progress has been undone. But the reliance of Western Europe on Russian gas affects current negotiations as well.

Germany, one of Russia’s largest gas buyers, has stepped away from U.S. calls for economic sanctions, although Europe is not immediately at risk of shortage if gas supplies from Russia are cut off. “Because of the importance of that gas trade we are going to see a very cautious approach,” from European leaders, IHS’s Sagers said.

“It could be just a reminder about where the western part of Europe gets its lifeblood from and what dependency could mean,” said Joe Kaeser, president and CEO of the German multinational firm Siemens AG. “Maybe the American people or government will ask, ‘How can the Europeans be so moderate about the debate of sanctions?’ Well, guess what? You don’t want to sanction anyone who you depend on.”

Policymakers have not been “asleep at the wheel,” however, Sagers said; European nations had invested in significant new gas storage and that the mild Western European winter meant that storage levels were “pretty healthy.” In fact, Europe could reverse pipeline flow to send limited amounts of gas east if necessary.

The European Union has also postponed talks regarding the proposed South Stream pipeline, another route for Russian gas to Europe bypassing Ukraine. Gustafson noted it as another point where previous progress between the EU and Russia would be destroyed. “Russia will be more determined than ever to build that pipeline, the EU may be more determined than ever to block it.”

Gustafson, Sagers and Stoppard spoke to a session of IHS’s CERAWeek conference, where a panel of people who study the region took a slot originally scheduled for the Ukrainian-born Russian minister of energy, Alexander Novak.

The situation emphasizes the way Russia has used its energy resources to achieve its policy goals, said Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-AK), speaking to encourage American exports of crude and condensate. Although the clash between the two countries was unpredictable, it will lead to a conversation about how countries are using their resources for leverage, she said, perhaps leading to a shift in perception domestically.

“We need to view our energy resources as an asset for global relations and greater stability within the world market.” As it is, Murkowski said, greater U.S. energy production has cushioned the global economic impact of unrest involving a major producer.

The crisis is also expected to increase the impetus for natural gas exports from the U.S. to Europe with the approval of more LNG export terminals, although even if various projects are approved, it will be several years before product can be shipped.

Comments