June 2013, Vol. 240, No. 6

Features

Shale Plays Should See Added Capacity Next 2 Years

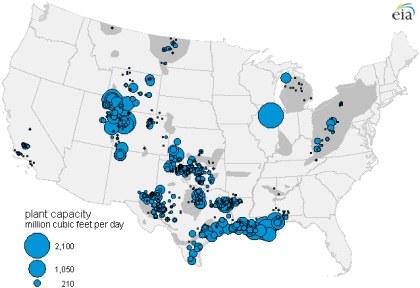

While the federal Energy Information Administration (EIA) may have first logged shale gas development and production as far back as the mid-1990s, it has only been in recent years that shale plays have become universally recognized as a game-changer for the energy industry.

As a result of the Shale Gas Revolution, dry gas production grew 15% to 11.3 Bcf/d between 2009 and 2012, and analysts expect that growth to continue, reaching an annual average of 69.1 Bcf/d by the end of 2014. This is despite currently limited takeaway and gas-processing capacity and the expectation of production declines in several major producing basins during the coming year, according to energy market analytics company BENTEK’s 2013-2014 Outlook.

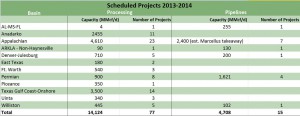

There are, at last count, 77 gas processing expansions and new projects scheduled to come online in 2013-2014, adding 14.1 Bcf/d of processing capacity, much of that accessible to shale plays. At the same time, 15 pipeline projects are expected to boost takeaway capacity by 4.7 Bcf/d — the lion’s share of that targeting bottlenecks in the Marcellus and Eagle Ford shales.

Additionally, Ohio’s emerging Utica Shale, which has almost no infrastructure to date, will benefit from several projects, including Tetco’s 300 MMcf/d pipeline expansion from Uniontown to Gas City.

As a whole, BENTEK estimated that limited capacity alone created an inventory of at least 1,800 non-producing or under-producing wells. Among that number were roughly 1,000 gas wells drilled in the Marcellus in 2012, even as some relief came in the form of eight Marcellus-related pipeline expansions, adding 2.0 Bcf/d by the year’s end.

“One thing to remember, to my understanding many of the producers had drilled wells simply to avoid leases expiring,” said Mark Bridgers, a design and construction consultant at Continuum Advisory Group in Raleigh, NC. “They are either waiting until there is a processing facility close by or, alternatively, the price of gas rises a little bit. Some of those wells that were drilled will be producing.”

He added that the ability to build processing plants in less than 24 months – and in some case less than a year – along with the “relatively easy” permitting process for such projects, make these projects easier to undertake than other types of infrastructure.

“Building a big one [processing plant] is not that problematic, either,” Bridgers said. “You need a little bit larger footprint, but these are not big land hogs.”

Said Don Warlick president of Houston-based unconventional oil and gas analysis company Warlick Energy, “There are new additions to petrochemical capacity going forward, right now. Essentially, all of these have a gas feed. That’s a very positive happening that, I think, will help gas prices.”

As additional gas processing, gathering infrastructure and pipeline capacity are built, particularly in the Northeast and South Texas, producers are beginning to tap into Marcellus and Eagle Ford well inventories and bringing production onstream.

While production volumes have flattened, BENTEK analysts expect dry gas to resume growth in the second half of 2013, due largely to the impact of the shale boom and the rapid growth of gas demand.

Lower Cost, Increased Efficiency

In addition to reduced cost, gains in drilling efficiencies are expected to quicken the rate at which the supply is delivered. BENTEK points, for example, to the Bakken, where the time to drill a well now averages 22 days, down from 36 days in late 2010. Keep in mind that gas-directed rig counts have declined 72% since peaking at 1,054 in September 2009, yet gas production grew by 15% during that period.

“The active count is a poor indication of production trend,” BENTEK said. “Drilling rigs can be vertical, horizontal, directional – with variation in horsepower, rotary steerable systems and torque/drag models, all of which affect drilling times and efficiencies.”

Additionally, production declines in several major basins are expected to be much slower in 2013, in part, because mature wells decline at a slower rate. BENTEK anticipates nine basins will grow in 2013, accounting for a 4.9 Bcf/d gain; however, declines in 10 others will drop the net gain down to 2.0 Bcf/d.

Major Shale Plays

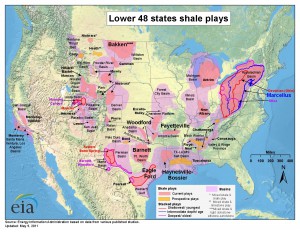

Marcellus Shale

When it comes to generating excitement within the industry, the Marcellus has led the pack for some time now. Located beneath much of the Northeast U.S., the play has been largely responsible for a huge bump in Pennsylvania gas production from 3.6 Bcf/d in 2011 to 6.1 Bcf/d in 2012, according to EIA data. This is despite a significant drop in total natural gas well starts.

However, seven projects expected online in 2013 and 2014 would provide 2.4 Bcf/d in new capacity to the Marcellus: Tennessee Gas Pipeline’s northeast upgrade, 636 MMcf/d; Transco Northeast supply link, 250, MMcf/d; Tennessee Gas Pipeline’s MPP project, 240 MMcf/d; Millennium Minisink compressor, 150 MMcf/d; Millennium Hancock compressor, 107 MMcf/d; National Fuel Gas west to east, 425 MMcf/d; and Tetco Team 2014, 600 MMcf/d.

In its new biennial report, nonprofit Potential Gas Committee’s (PGC) estimated the U.S. Atlantic region, which includes the Marcellus, holds about one-third of the nation’s shale gas – 741.32 Tcf. The whopping 110% increase of 384.72 Bcf in the region since 2010 was attributed “almost entirely to re-evaluation of the Appalachian shale gases – primarily the Marcellus.” However, it also included the Utica Shale, which was assessed by PGC for the first time.

While calling the re-evaluated numbers “surprising and quite upside,” Warlick said it is important to remember Marcellus drilling is taking place almost exclusively in Pennsylvania, but the shale itself extends well into New York, Ohio and West Virginia.

“While drilling in New York is essentially nil, the potential for the Marcellus is translated over the extent of the shale, so it gave support for this upward revision,” Warlick said.

The Devonian Age shale covers 104,067 square miles with a potential for 90,216 wells, according to EIA.

Haynesville Shale

In 2011, Haynesville Shale in Louisiana surpassed the Barnett Shale in Texas as the nation’s highest producing shale gas play based on reported pipeline flows, according EIA. Vertical drilling had been in use at Haynesville since 1905, but not until the introduction of horizontal drilling had the formation been considered a key gas source.

Earlier experience gained from horizontal programs at the Barnett played a major role in Haynesville, allowing producers to ramp up natural gas production as quickly as they did. Based on reported flows, it took about 10 years of shale-focused drilling to reach 5 Bcf/d at the Barnett — a mark surpassed at the Haynesville within three years while using many fewer wells.

The 9,320-square-mile play, which EIA estimates has 75 Tcf in shale gas resources with a potential for 65,860 wells, has been buoyed by the addition of fairly new regional infrastructure, including the completion of pipeline capacity expansions on the Regency, Midcon Express and Gulf Crossing systems.

Barnett Shale

Until the Haynesville came along, the mature Barnett Shale had been the leading shale gas producer for a decade, having become viable with the advent of horizontal drilling. As a “tight” gas reserve, the Barnett has seen operators refocus more on liquids-rich areas of the play as gas prices stay relatively low.

The Barnett lies beneath Fort Worth and extends as far as West Texas, encompassing at least 17 counties. It is estimated to have 43.4 Tcf of shale gas technically recoverable resources (TRR), according to EIA.

Bakken Shale

Much like the Barnett, Bakken Shale drilling activity built up gradually and eventually led to rapid growth, accelerating 71% to 594,000 bpd in year-over-year June comparisons of the past two years, according to EIA data. The 200,000-square-mile play in the Williston Basin now accounts for 90% of North Dakota’s oil production.

Not surprisingly, the production gains in the Bakken have been spurred by accelerated development, most notably horizontal drilling combined with hydraulic fracking. The North Dakota Department of Mineral Resources reported a total of 4,141 producing wells in the state’s Bakken region, an increase of 4% between May and June 2012. For the same period, the Williston Basin had a weekly average of 209 active horizontal rigs — most of those are positioned in the Bakken.

Bakken production, which averaged a little more than 2,000 bpd in 2000, grew to average more than 260,000 bpd in 2010 with horizontal wells accounted for nearly 90% of total 2010 volumes.

Fayetteville Shale

Located in the Arkoma Basin of Arkansas, the recently developed 5,853-square-mile shale play has proved to be a profitable one for both oil and gas companies. With TRR of 13,240 Bcf and the potential for 10,181wells, the Fayetteville contains shale gas resources of 32 Tcf, according to EIA.

Woodford Shale

Although gas production in Oklahoma’s Woodford Shale began in 1939, there were only 24 gas wells in the region as recently as 2004. However, by 2008, there were more than 750 gas wells in the Woodford, which flourished when horizontal wells swept the play.

Production in the 6,350-square-mile Woodford has been in decline in recent years, but EIA’s 2012 outlook showed shale gas resources of 22 Tcf with a potential for 5,428 and 3,796 wells in its Arkoma and Anadarko Basin locations, respectively.

Notable Shale Plays

• The Utica Shale, which lies beneath New York, Pennsylvania, West Virginia and parts of Canada, continues to have a vast amount natural gas and liquids to offer with BENTEK anticipating an average annual production increase of 340% to 330 MMcf/d for 2013 and 399 MMcf/d for 2014.

With Chesapeake Energy and Devon Energy having put Utica land up for sale recently, some analysts see this as a sign the Utica will evolve into more of a gas play than oil play.

To a large extent, severe infrastructure restraints have left producers somewhat in limbo. However, considerable relief in the form of several projects is near at hand. One of the biggest, the Utica East Ohio Buckeye, is expected online shortly and will have an initial capacity of 600 MMcf/d to go along with NGL storage capacity of 870,000 bbl and fractionation capacity of 90,000 bbl/d.

However, as Bridgers sees it, companies are already working aggressively to get facilities online and the political environment is good in the region.

“Both Pennsylvania and Ohio have been very encouraging of this type (shale-related) of exploration and production,” he said. “The processing plants are part of that exploration and production activity, and they are going to be very supportive of that as well.”

• Antrim Shale is located in the Michigan Basin at a relatively shallow depth of about 1,000 feet. Vertical wells have dominated the play for decades and horizontal drilling is not common. EIA estimated the play has 20 Tcf of shale gas resources in reserve.

• Caney Shale in the Arkoma Basin of Oklahoma has only recently been developed, following success in the Barnett Shale. In its 2012 outlook, EIA estimated 29% of the 2,890-square-mile area had the potential to support 3,369 wells.

• Gothic Shale is a new shale formation development located in the Paradox Basin of Colorado. So far, only a few wells have been drilled. Bill Barrett Corp. has reported rates in the play of between 1.5 MMcf/d and 4.9 MMcf/d, estimating 58 Bcf gas-in-place per section in the Gothic Shale based on core.

• New Albany Shale is in the Illinois Basin and has been the site of gas drilling for more than a century. Most wells are shallow, between 120 feet and 2,100 feet deep. New drilling methods and other improved technologies have combined with higher natural gas prices, causing some producers to take renewed interest in old leases and drill new wells. EIA estimates New Albany Shale gas resources at 11 Tcf.

Editor’s Note

For an update on the Eagle Ford Shale, see “Investment And Production Reach New Highs In Eagle Ford, Pipelines Lag Behind” in the May 2013 edition of P&GJ.

Comments