September 2009 Vol. 236 No. 9

Features

SCADA Security, Compliance, and Liability A Survival Guide

Two hot topics in the industrial world are security and compliance. Controversy surrounds the interpretation of how to address them.

Although regulatory bodies, industry trade groups and industry participants are working to provide concise guidance, no definitive roadmap exists to achieve full compliance.

Operators face an almost overwhelming number of standards, guidelines, and best practices that require interpretation with little guidance. Operational and security requirements are often confusing, sometimes inconsistent. Security-related documents often purport to be the required standard even when they are not while security programs are not tailored for specific operations.

Addressing this requires an understanding of the requirements and development of an appropriate solution. While a one-size-fits-all solution is not possible, there is a process that aggregates the requirements and best practices available to industry, allowing each company to design and implement a solution that makes sense for its organization and facilities. This holistic approach offers a roadmap to help achieve compliance and avoids the fatal error of looking at security as simply an “add-on” issue to operations. The pitfall with that approach is that these narrowly focused security solutions may temporarily address technical requirements while failing to consider additional requirements related to compliance with evolving regulations and standards.

SCADA (Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition) systems users are the most affected by the increase in recent activity. On the security side, SCADA operators are confronted with the lingering “IT vs. SCADA”, or “them vs. us”, issue, along with the cyber-security threat debate. One faction sees a valid cyber threat to critical infrastructure. Another believes the real threat lies in other factors such as physical or human-risk issues. We believe both threats are real and need to be addressed. With compliance activity rising, operators must interpret and potentially comply with the myriad of standards, guidelines, and best practices that have been released.

Unfortunately, these documents provide little guidance on exactly which standard or best practice addresses those threats confronting operators. Even in more regulated industries, such as electric utility where definitive regulatory guidance has been established with NERC CIP, the requirements are still so vague and watered down that neither security nor compliance is assured. All of these issues have the potential to cause serious repercussions to an organization as an incident or an audit failure could result in significant financial loss. This article addresses these issues, taking the holistic approach.

Where Is The Threat Anyway?

Is there potential for an actual cyber threat or is it just media hype? In short, yes – cyber threats do exist for SCADA systems. Is the potential for cyber threats as great as some claim? Probably not. Many have asked, “If there is no hard-core evidence of a significant [outside] cyber attack on an industrial network, where is the threat?”

These types of threats are becoming more likely as SCADA systems and networks increasingly utilize commercially off-the-shelf (COTS) software, connect to the enterprise layer and move toward IP connectivity. This has contributed to higher threat levels and increased vulnerability.

A few years ago, the chances of someone finding and exploiting these vulnerabilities were very slim because process-control systems and SCADA networks were unheard of by the general population and systems were based on specialized platforms that were segregated from the enterprise layer. Industrial systems have begun to take a front seat in the spotlight due to the focus by the Department of Homeland Security on national critical infrastructure and some unfortunate media coverage.

Evidence recovered from al Qaeda suggests terrorists are interested in our SCADA networks (see, for example, March 11, 2005 Washington Post article “Hackers Target U.S. Power Grid”). In addition, the number of “SCADA hacking” presentations is increasing at security and “hacker” conventions, with the number of vulnerabilities discovered within these systems increasing.

While cyber security is getting most of the attention, with hackers already attracting premature blame from a few recently publicized incidents, the widespread disregard for physical and operational security within many organizations is now a huge concern. Many companies are heavily focused on shoring up their cyber security with little or no regard for physical security.

Though most standards emphasize cyber security, physical and operational security weaknesses can provide an alternate attack vector to SCADA systems and networks. When asked to perform penetration testing of company systems, we have experienced a 100% success rate at gaining unauthorized cyber access by taking advantage of neglected physical and operation security controls. Companies that have addressed cyber, physical and operational security will be much better positioned to defend themselves. Taking this holistic approach will address the threats posed to their systems and those posed government, media, and lawyers who will want to assign fault if a security breach leads to an incident.

Regulatory Confusion

Beyond potential cyber, physical and operational threats, operators must contend with regulatory compliance. This landscape is complex environment in that each industry vertical must navigate through multiple regulatory requirements, industry standards, guidelines, and best practices. Most of these documents are very ambiguous with little consensus on strategic guidance or tactical implementation.

Asset owners and operators across all industry verticals are not only unsure as to exactly how they must meet compliance and secure their systems, but also to what standards, guidelines, or best practices they may be held accountable. As a result of the lack of clearly delineated requirements, operators are susceptible to various interpretations. This could lead to an audit failure or out-of-context scrutiny subsequent to an incident leading to penalties and potential legal liabilities.

Where Are The Liabilities?

The regulatory environment is placing increased demands on SCADA systems, driving data capture and retention, documentation, training, security, policy, and reporting requirements. Operators and vendors are working to incorporate the impact of regulatory and legal issues into the design and use of the systems.

Legal requirements and trends have increased emphasis on maintaining compliance because these issues are subject to increasingly aggressive enforcement. Compliance is of great significance in any incident where SCADA systems may be a core component of an investigation, lawsuit, or regulatory enforcement action. Compliance failures have resulted in large fines, jail time, injunctive relief and bad press.

Threats to operators also include the potential for misinterpretation and misuse of data. Knowledge of the data, and the obligation to understand what it means or implies, will be imputed to operators and management. Responsibility and punishment will reach into the highest levels of management. Operators and management face potential charges of negligence being changed to allegations of willful misconduct. They also confront the possibility of criminal liability and increased civil exposure.

Businesses with any form of SCADA-controlled operations must be aware of potential liabilities and take prompt action to minimize them. Personnel with the responsibility and expertise to manage SCADA for and in these businesses are the first line of defense against charges of noncompliance violations and lawsuits. They should be able to recognize the exposures faced by the company if the SCADA system (or an operation controlled by SCADA) fails operationally, suffers a security breach, or is in violation of compliance issues.

The following scenario illustrates the types of issues that can flow from a failure in an operation, especially a failure where an incident occurs.

If an operation fails in any way that is significant outside of the company, it usually follows that agencies and other outsiders will become involved. “Significant outside of the company” can mean an adverse economic impact on a third party (“the pipeline went down because of a leak, resulting in gasoline supply disruption”), damage to the environment, or injury or death of any person (including an employee).

The outsiders will look at the failure and the company, either because they have the public charter to do so (the FTC at supply disruption, DOT at pipeline safety issues, OSHA at injuries or deaths of employees, law enforcement or injury or death of third parties, the EPA at environmental issues, etc.), or because they see an opportunity to make money (plaintiff lawyers). They will look at operations with 20/20 hindsight and, depending on the incident, may look deep into records, security, policies and procedures and company decisions.

Although a failure may be SCADA related, the cause of the problem is usually external to the SCADA system. Provided the SCADA system is integrated correctly (incorporating the holistic model consisting of operations, security, and compliance), it can help answer what caused the problem.

The SCADA records likely will have a critical place amid the scrutiny. The first hurdle facing the company is ensuring that the records can be produced. There are certain requirements in regulatory schemes for records retention (for example, see 49 CFR 195.404 regarding liquid pipelines in the U.S.). Failure to produce the required records may not only be a violation, but may also raise a presumption that the company destroyed the data because it has something to hide. If a civil lawsuit is filed, rules regarding evidence preservation may come into play, along with issues regarding records that are part of common law requirements as well as regulations like Sarbanes-Oxley in the U.S.

Assuming records and data are available, they will be dissected to find any “problems” in operations. Regulators and plaintiff lawyers will also look at compliance, training given to operator personnel, the manuals and policies underlying training, the age and physical security of the system, the ergonomics of the SCADA control room and system, and many other factors to find fault with the company. Even if the incident resulted from a security breach caused by a criminal act of a third party, the company will be held responsible on the theory that its security, because it was breached, was obviously insufficient.

Vendor exposures are also multi-faceted. During investigation, vendors will be subject to subpoena and discovery by regulators and plaintiff lawyers seeking information about the vendor’s activities on behalf of an operator. Vendors will need to have maintained their working files in accordance with the requirements of the operator’s contract. Although contracts normally require the vendor to provide prompt access to its records and files, such access is predicated on auditing by the operator of the vendor’s work, rather than seeking to preserve records that may become important during a probe or litigation.

In the best of circumstances, vendors can plan on having business disrupted if their client has a problem. In worse cases, the vendor can plan on being a defendant. In this scenario, the vendor may face the choice between accepting some liability or blaming its customer for the failure. The latter action may result in the vendor crippling its business prospects with not only the customer involved, but other operators in the industry.

Addressing The Current Environment?

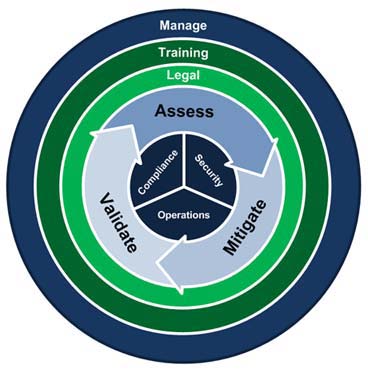

The most comprehensive way to address each of these issues is with an approach that spans across compliance, security and operations. The Holistic Lifecycle Model for Security and ComplianceTM consists of proven methodologies aimed at critical infrastructure and industrial environments. It is designed to assist operators with maximizing security and achieving regulatory compliance while minimizing liability from legal action and broad auditor interpretation. The model spans across all aspects of compliance, security and operations by including methods for proper standards/guidelines/best practices selection, security assessments (physical, facility, cyber, and operational), gap analyses, risk analyses, organizational threat modeling, mitigation/remediation strategies and integration, legal support, and management/maintenance programs.

The following section will address the basic flow for each phase of the model. Much of the technical detail goes beyond the scope of this article and is highly dependent on direct interaction with each individual operator’s environment.

Phase 1 – Assessment

Whether you are using a self-assessment tool such as CS2SAT, or a third-party consultant to perform a Security Vulnerability Assessment (SVA) or Gap analysis, the goal is to identify vulnerabilities and/or gaps in your environment. An SVA or gap analysis alone will not ensure that your organization is secure or compliant. In fact, if done improperly, they can actually create liability for your organization. Many organizations are not aware of the many necessary steps to a proper assessment, which are all part of a larger lifecycle that help build solid due diligence.

A complete assessment phase consists of the following steps:

1. Standards Identification and Selection – The first step in achieving security and compliance is to initiate an exhaustive search of all the regulatory requirements, industry standards, guidelines, and best practices that may fall within your industry vertical. Even if some of the standards, guidelines and best practices were originally intended for another industry vertical, it is recommended that you review and/or include them in the list of potential requirements to achieve compliance.

This list can then be narrowed to the handful of documents that you believe provides the best set of requirements matching your organization’s infrastructure. The idea is to show you have performed due diligence in your research and exclusions to achieve compliance in the event an auditor or attorney doesn’t see a specific document referenced. All of these documents must now be put into a matrix, identifying a comprehensive list of categories, cross referenced to the relevant sections in each document.

2. Policies and Procedures Analysis – Once you have created the regulatory requirements, industry standards and best practices matrix, your organization’s internal policies and procedures must be added to ensure compliance with corporate mandates. A policies and procedures analysis should be performed. Personnel interviews should be added for improved accuracy. This will tell you how well your written policies and procedures cover the regulatory requirements, industry standards and best practices contained in the matrix.

3. Critical Asset Identification and Classification – Certain industry verticals require identification of critical assets by quantifying certain attributes. This should be done according to the standards for that particular industry vertical with the understanding that this process may be governed by specific regulations regarding confidentiality and management of information.

4. Security Vulnerability Assessment (Cyber, Physical, and Operational) – The majority of standards, from all industry verticals, prescribe at least some version of an SVA. These typically focus on cyber elements, leaving gaps in compliance and security. Even if you are only concerned with the cyber aspects of compliance and security, you are still leaving vulnerabilities in your cyber security, as the physical, operational, and human elements can provide an attack vector to your cyber systems. It is highly recommended you also perform tests to include a physical SVA and/or a “Red Team” test. These tests will help evaluate all aspects of your cyber, physical, operational, and human factor security.

(Technical Note: Only proper SCADA or process control system (PCS)-approved assessment methods should be used to assess these environments. Such methods should only be performed by individuals with extensive experience in assessing and testing SCADA and PCS environments. For example, all tests should be run on a backup system, in a test lab or another form of non-production environment of like systems and configurations. Only very specific true passive tests that have been proven safe on non-production systems should be performed on production environments).

(Legal Note: It is critical how an operator documents and communicates the results of any SVA. Failure to manage the documentation may result in the assessment simply serving as a road map for attorneys or agencies to attack security programs. Such misuse can happen even if such attacks take the necessary self-critical analysis involved out of context and fail to consider that the company based security decisions on a risk matrix that carefully considered probability and consequences to address the most viable and serious threats).

5. Assessment Validation – All analysis and SVA results must be validated. This can be accomplished by a combination of results analysis, penetration testing and interviews. For cyber assessments, simply running vulnerability assessment tools such as Nessus and reconnaissance tools such as NMap will not achieve a complete and proper vulnerability assessment. In addition to leaving gaps in security, these tools can produce false positives as well as false negatives.

(Technical Note: It is critical that proper SCADA or process control system-approved testing methods be used to test these environments.)

6. Risk Analysis – All of the data gathered thus far in this phase must be analyzed to provide a clear picture of the levels of security, compliance and risk. Any risk formulas and threat models used should be specific to your industry and customized for your organization. This can be a complex step, requiring an experienced professional versed in risk-analysis formulas and threat modeling.

Phase 2 – Mitigation/Remediation

In this phase, policies and procedures will be revised and enhanced to reflect the current environment. A mitigation strategy will be built, based on the data from the Assessment Phase, with mitigation/remediation solutions identified and put in place. We are often asked, “How do you know that your interpretation of the standards is correct when developing policies and procedures and mitigation/remediation solutions?” What is important to remember is that the standards, guidelines and best practices are not being interpreted. They are being referenced by specific section in the matrix. If you can show that you have performed exhaustive due diligence in an effort to clarify and satisfy any vague requirements of a particular standard, you should have a solid defense in event of an audit or possible litigation.

Phase 3 – Validation

Validation verifies that implemented remediation and mitigation have been deployed and are being effective at improving security and achieving compliance. This is accomplished by revisiting certain aspects of the Assessment Phase. A complete vulnerability assessment should be re-run, along with any other step from the Assessment Phase, to address any key areas of concern. Use this phase to fine-tune strategies and solutions as needed. The Validation Phase should be revisited at least once a year or as prescribed by changes in regulatory, industry and corporate requirements in the particular industry vertical.

Phase 4 – Legal

Many organizations are not aware that simply performing an SVA or other self-critical analysis can actually create liability if the data is not properly handled. It is also very important to remember that improper standards and best practices selection can create liability as well. The following questions must be asked: Has the organization performed the necessary due diligence and covered all angles necessary to prevail, should someone take legal action against you as a result of an incident? Is the organization prepared for auditor interpretation that could lead to regulatory fines? The Legal Phase is active throughout the entire holistic model lifecycle, ensuring no other processes undertaken in good faith to reduce risk have the unintended result of creating liability, both short and long term, for the organization, and that regulatory changes are worked into the model.

Phase 5 – Management

Once remediation and mitigation have been deployed and validated, a long-term program must be put in place to ensure that all processes, procedures, and technical safeguards are monitored, maintained and kept current with emerging threats and changing industry requirements.

Phase 6 – Training

Training is a critical part, if not the most critical part of the holistic lifecycle model to achieve security and compliance. All stakeholders must be trained in understanding the strategic approach and tactical implementation of the model or the organization will not achieve the desired outcome. Training is referenced in many of the regulatory requirements and industry standards as a critical component of security and compliance. A training program should be developed and implemented with a strong communication component to ensure success. All stakeholders should have a clear understanding of roles and responsibilities, communication security and protocol, and document security and transmission protocol.

Conclusion

Security issues with SCADA systems are rapidly expanding, creating new challenges for operators. This escalation in security concerns is due to increased awareness of these systems, changes in systems and configurations, creating new – and in some instances – increased vulnerabilities, and personnel (training) related issues in increasingly complex environments. Taking the necessary steps to identify and address these risks is not an option, but an imperative. Coupled with emerging security challenges, changes in the current regulatory environment of increased enforcement has compelled operators to address compliance with regulatory requirements, industry standards, industry guidelines, industry-best practices and corporate policies and procedures.

Companies have a duty to address compliance and security issues. The Holistic Lifecycle Model for Industrial Security and ComplianceTM provides the framework to develop an on-going process to achieve necessary levels of security while addressing compliance. It was designed to assist operators of industry control systems in meeting security and compliance in the rapidly changing environment. Operators that use this approach will have a greater understanding of current and emerging requirements, their infrastructure and the solutions required to achieve security, compliance and operational objectives.

Authors’ Note:

The information herein is not, nor is it intended to be, legal advice. You should consult an attorney regarding your particular situation. We reserve the right to determine whether to accept any matters referred to us for representation. Until we have agreed to being hired by you in regard to any legal matter, we are not your lawyers. Never send confidential or sensitive information to us by e-mail without our permission. By sending such information, you may be waiving any potential attorney-client confidentiality privilege.

Authors

Clint Bodungen has experience in physical and systems security, most of which has been dedicated to industrial systems, process control, and SCADA. He was a Computer Systems Security Officer and Operational Security Manager in the United States Air Force. He was the co-founder of the Critical Infrastructure Institute and the founder/principal analyst of CIDG, Corp. (Critical Infrastructure Defense Group), where he continues to perform PCN/SCADA security assessments, red team testing, and regulatory compliance consulting.

Chris Paul focuses his practice on transactional and regulatory matters, including related litigation. He has extensive experience with pipeline issues, including transactions, integrity programs, SCADA auditing, contracting, and emergency response and litigation. He is admitted to practice in Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Arkansas and Kansas, the U.S. Supreme Court, and various U.S. District Courts.

Jeff Whitney is an entrepreneur and computer professional with 25 years of management and technical experience in Real Time (Mission Critical) Process Control Systems. He has extensive experience assisting pipeline companies with SCADA system integration, SCADA security, SCADA consulting and Compliance. He is an owner/principal of Berkana Resources Corporation (BRC).

Comments