October 2016, Vol. 243, No. 10

Q&A

Legal Tips on Planning Natural Gas Pipeline Projects

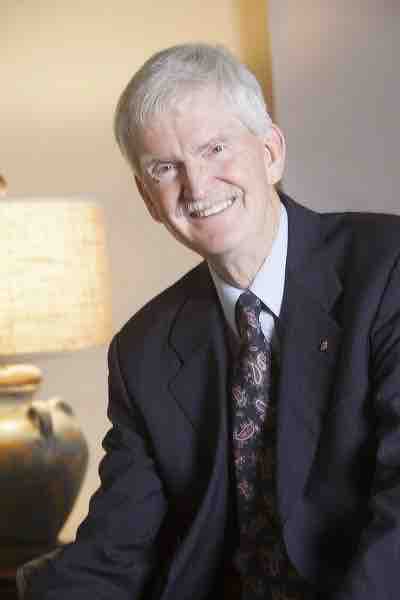

Michael Rutter, a partner in the law firm of Rutter & Roy, is known for his legal expertise in the planning and development of federally regulated pipeline projects. With deep roots in New Jersey, the firm began representing its first interstate natural gas pipeline client in 1950. Since then they’ve helped clients save time, money and avoid potential show-stoppers.

From acquisition and planning through construction, permitting and restoration, natural gas pipeline projects can be complex and challenging. Rutter has seen first-hand the multitude of issues that pipeline development projects face, especially in today’s hyper-connected world where projects are heavily scrutinized and misinformation is rampant. While pipeline construction has been increasing in the nation, Rutter has seen opposition campaigns from residents, environmentalists and national organizations also rise in numbers and activity.

There is no typical pipeline project as each has its own set of challenges, depending on its location and environmental issues. As Rutter notes, the key to tackling challenges and minimizing potential delays that could occur during development of a project is through proper project planning. The first step is to get the legal team involved early in the planning phase. The legal team can help coordinate the different phases of the project – making jurisdictional determinations, identifying regulatory triggers, creating milestone schedules, identifying publicly owned lands, planning for appeals and coordinating with public outreach.

Rutter has over 35 years of experience, focusing on pipeline law, condemnation, real estate law and environmental law. He did his undergraduate work at Rutgers University and earned his Juris Doctor degree at Seton Hall University School of Law.

P&GJ: What is a company most likely to overlook during the process?

Rutter: Without a doubt, it is property restrictions, particularly in northeastern states where we’re dealing with a stricter regulatory climate. In New Jersey, for example, plans to build new pipelines many times involve going through preserved open space, preserved farmlands, wetlands, etc. Most states have equivalent programs and jurisdictional boundaries need to be established to determine how to proceed.

As far as property restrictions, there are three major categories in New Jersey:

- Green Acres

- Preserved Farmland

- Conservation restrictions

The one that tends to be overlooked the most is Green Acres because the designation is not easily found in public records. In New Jersey, there is what’s known as unfunded Green Acres. It includes all open land owned by any local unit (municipality or county) that is used for recreation or conservation purposes, even if it wasn’t acquired with Green Acres money, so long as it was owned at the last occasion that the local unit received money from Green Acres. When a town or county tries to develop that open land, they may come across a local group that will object, maintaining that the property should be considered to be Green Acres-restricted.

Another restriction specific to New Jersey is the No Net Loss Reforestation Act, which states that if one-half acre or more of wooded land owned by a state agency is disturbed by the proposed project, then trees would need to be replaced either onsite or offsite. As with Green Acres-restricted properties, there are public hearing requirements and the replacement requirements can be costly.

When you’re dealing with linear projects, restrictions tend to be overlooked even after a title search is conducted. But once they’re identified you have to know what to do next, and whether you can work with the restrictions or might have to condemn the property interests required for the project.

P&GJ: What causes the biggest snags along the way, or takes up more time than anticipated?

Rutter: Creating a milestone schedule is a crucial part of the planning phase and saves our clients a lot of time in the long run. We start with the project’s proposed in-service date and work backwards from there. Next, we take into account the time and documents needed to condemn property rights that couldn’t be negotiated, including Green Acres restrictions.

At that point, there are two things that take the longest to get and are more likely to hold up a project – drawings and appraisals. Good drawings not only show a property’s location and width of existing and proposed easements, but can also be used for appraisals. Appraisals indicate how much impact the proposed easement will have on the property, determining the property’s value both before and after the project is completed. Typically, people believe that a pipeline project devalues their property, but that’s not true at all. In fact, it has very little impact on the value, but that reality is counter-intuitive.

Appraisals can take an amazingly long time to get done, particularly if there are a lot of them. So don’t try to save money by putting appraisals off until you’re ready to condemn. Appraisals are time-consuming and will push your milestone schedule if you order them too late in the process.

Additionally, in recent years, appeals have become a major snag. It used to be that requests for re-hearings, and subsequent appeals, focused on the certificates of public convenience and necessity of ordering construction of projects issued by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). But now, even before an application is made to FERC, you must anticipate appeals of state environmental permits. Attorneys need to be involved in reviewing these applications because vaguely written permit applications leave issued permits vulnerable to appeal. Permit applications should be treated as legal documents. In the past five years, we’ve seen so many appeals of state permits that we now recommend budgeting for them at the outset in order to be prepared.

P&GJ: Is it best for pipeline representatives to get into a community early and present plans before there has been adverse publicity and protests?

Rutter: Yes, contact residents and elected officials early on and keep them informed of planned projects. You don’t want to take anyone by surprise. It’s also best to do it before any pre-filing with FERC, which is 9 to 12 months before the main application. An effort should be made to engage the local community, get the facts out to local leaders and address any concerns. Educating residents and business owners and creating consistent messaging will prevent confusion.

We’ve seen opposition groups spring up overnight because people can go online and find a blueprint for how to oppose and try to stop a proposed pipeline project. There is an amazing disregard for the truth in these opposing campaigns, and the misinformation will flow very, very quickly.

P&GJ: At what stage is it best to meet with owners of property to be acquired – prior to any group meeting with the community?

Rutter: Obviously, you need to contact landowners before they read about it in the newspapers, and way before the scoping meeting scheduled by FERC or the open houses held by the pipeline companies. You’ll also likely need permissions for various surveys.

You can begin to negotiate for acquisition as soon as it is decided that the landowner’s property will be impacted or affected by the construction route. It is helpful to identify as early on in the process as is possible which landowners are most likely to sign an agreement.

You will want to do the following:

- Create a spreadsheet to keep track of landowners and your interactions with them; and

- have a form of agreement ready for the landowner’s execution (vetted by the attorneys).

You want to allow enough time for negotiation but, if you are unable to come to an agreement by the milestone schedule deadline, you should be ready to condemn. Because the project will likely create a long-term relationship between the owners and the company, avoiding litigation is certainly preferable.

P&GJ: Do you have an example of a pipeline project in which advanced planning has been carried out well?

Rutter: Advance planning is a problem-spotting issue. Roughly three years ago, there was a project built in New Jersey where the issues were spotted well in advance. It was probably the last project before environmental groups started appealing permits issued by the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection. Everything was done right, including identifying the preserved farmland and all of the Green Acres properties, as well as federal conservation restrictions.

Also, there were two or three towns and one county that absolutely would not agree to have the project cross their Green Acres encumbered properties. So it was necessary to acquire the Green Acres easements by condemnation. At least in that case, knowledge was power. Essentially, the pipeline company, in the litigation, honored the Green Acres regulations without the cooperation of the county or municipalities.

Advance planning was carried out well. It wasn’t that there weren’t difficulties – there were tremendous difficulties. But they were identified several years in advance, and a record was developed of how the pipeline company tried to deal with the issues. Once the FERC certificate for the project was issued, we were able to go to court to acquire the rights needed for construction.

Comments