August 2016, Vol. 243, No. 8

Features

Dakota Access Pipeline: A New Artery for Bakken Crude

The past two years (2015-16) will not be remembered as anything like the preceding ones of robust growth when new energy infrastructure was sprouting up like weeds, particularly on the North Dakota prairie atop the Bakken Shale play, and Justin Kringstad has had a front row seat on the roller coaster. As director of the North Dakota Pipeline Authority, Kringstad says “it has been quite an interesting ride” the past eight years.

Uncertainty now runs through the midstream sector the way pipe- and pump-laden trucks used to rumble through the Bakken-Three Forks in Kringstad’s state in which he is a facilitator, not a regulator. “The midstream industry doesn’t like uncertainty, so when companies plan projects, they ideally like to have committed volumes with the certainty that production will be there, and it will flow on their transportation systems.”

The last two years of price fluctuations and severe downturns have caused many of the companies that Kringstad has worked with in his job to re-evaluate major new infrastructure projects. The trick is always to plan the right size project for the right time, he says. “Trying to predict that in the mid-2016 environment is incredibly challenging.”

“Two or three years ago, it was hard to make a bad midstream decision because anything you built was going to be full whether it was a processing plant or a pipeline,” Kringstad says. “Now there is still a lot of uncertainty about what the future is going to look like and the timing for whatever permanent recovery that may kick in. It’s unclear that all the midstream companies will be ready for any ramp-up that comes.”

In terms of fluid transportation (oil and water), as Kringstad calls it, in North Dakota there are significant projects needing to be developed as the Bakken play, which many see as still in the early stages of its productive life, matures further. “We’re going to continue to see, percentage-wise, more barrels being put in a pipeline as opposed to being moved by rail,” he says, noting that this makes projects like the Dakota Access oil pipeline aimed at moving large quantities of Bakken crude to distant markets much anticipated additions for the American energy infrastructure landscape.

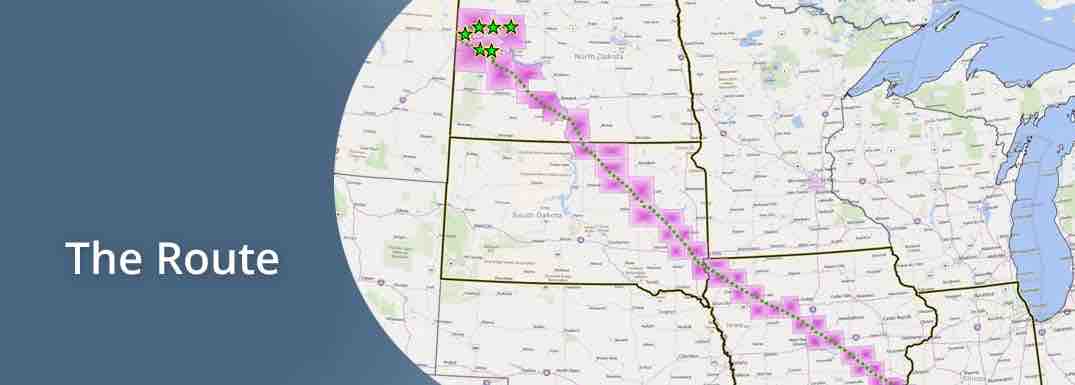

As Kringstad attests, nothing is ordinary about building an energy carrying pipeline these days, so it’s easy to realize that the $3.78 billion, 1,172-mile Dakota Access oil pipeline now under construction in four states out of North Dakota’s sweet crude-producing Bakken is extraordinary by just about any measure. With a seasoned engineer’s typical understatement, senior vice president for engineering at the project sponsor, Energy Transfer Partners (ETP), Joey Mahmoud told a gathering in late May in Bismarck, ND, that Dakota Access is a “pretty important project for the Bakken.”

With the extraordinary growth in production in the Bakken prior to the commodity price crash in the latter half of 2014, ETP’s Dakota Access is not building any of the gathering system; that’s in place to the tune of about 2 million bpd capacity, Mahmoud said at the Williston Basin Petroleum Conference, which drew nearly 3,000 participants. This is a big-scale mostly 30-inch pipeline that promises to get Bakken supplies to various hubs in Illinois that are linked to Gulf and East Coast markets.

It will transport 450,000 bpd with a capacity as high as 570,000 bpd or more – which could represent half of the average Bakken 2016 daily crude production. Mahmoud and his marketing colleagues say shippers will be able to access multiple markets, including the Midwest and East Coast, as well as the Gulf Coast via the Nederland, TX crude oil terminal facility of Sunoco Logistics Partners.

Designed with the most advanced safety and efficiency aspects, Dakota Access Pipeline LLC is sparking interest from distant refiners because it promises so-called “clean barrels,” according to its engineers.

“What is put in the system in the Bakken is what the refiners get at the other end,” Mahmoud says. “Those barrels can travel all the way to the Gulf as clean barrels, so that is one of the seamless optionality services that we can provide.”

Other than some producers taking off their oil at Patoka, IL, [the end of the Dakota Access line] to go to the Chicago area or the East Coast, those barrels can go all the way to the Gulf Coast as a clean barrel head,” Mahmoud says. With the decline in commodity prices and the buildout of more gathering and processing infrastructure, amounts of Bakken crude shipped by rail continue to decline. ETP is betting the need for pipeline capacity will keep expanding, and North Dakota’s Kringstad agrees.

The economic impact of the project cannot be overstated in the four states it will traverse (North and South Dakota, Iowa and Illinois), according to ETP and executives like Mahmoud. There is over $1 billion in pipe and other related equipment for the undertaking that were apportioned to the various construction spreads early in 2016. “Everything except for a couple of pumps and a little bit of pipe was made here in the United States,” Mahmoud says.

“From a manufacturing standpoint, the project has been a huge boost, so it’s not just from a labor standpoint. All the materials that possibly could have been sourced were right here, so an overall $3-4 billion job like this has a total impact of about $20 billion on the economy. This is a huge windfall for our country, and we’re pretty fortunate to be able to develop this project that will need about 12,000 construction workers by the time it’s finished in early 2017.”

All of the contracts for building the line were in place at the time Mahmoud spoke to the Bakken audience, which included representatives of service companies supporting the longstanding, state-supported project.

Last fall, a unit of Tulsa-based Matrix Service Co. won the bidding competition to build six gathering terminals, all in North Dakota, for feeding the oil pipeline. At the time, Matrix officials said the engineering, procurement and construction contract for the terminals was valued at about $330 million to the company. Each terminal will have working capacities of 200,000-600,000 bbl. In mid-2016, all six sites were under construction.

“We’re going to build all 2 million barrels of storage within a year’s time,” says Mahmoud, noting that a relatively mild North Dakota winter helped to stay on schedule.

As reported earlier, Precision Pipeline LLC is building six of nine construction spreads – three in North Dakota and the rest divided between Illinois and Iowa, Mahmoud says. Others are being built by Michels Corp.’s Michels Pipeline Construction unit in South Dakota and Iowa.

As part of the agreement, Brownsville, WI-based Michels Pipeline and Eau Claire, WI-based Precision are using 100% union labor, with half of the workers sourced from local halls in each state the pipeline crosses, according to ETP. In anticipation for the project getting built in 2016, Michels and Precision made early commitments exceeding $200 million to Caterpillar, John Deere and Vermeer for heavy construction and related equipment. They bet on the outcome as ETP’s pipeline unit representatives were still securing final state regulatory decisions in late 2015 and early 2016.

Michels, with a field office in Cedar Rapids, IA, is constructing segments in Iowa and South Dakota and North Dakota, while Precision has segments in Iowa and Illinois. Collectively, Michels and Precision are employing up to 4,000 people per state. Michels is also building the pump stations.

“North Dakota couldn’t supply 50% of the labor force, but the local halls in the state are supported by some of the supporting personnel in the region,” Mahmoud says. “Overall, the project is a pretty big windfall for organized labor. At the start we had $1.5 billion in pipe and other materials on the ground in one spot. It was a neat thing to see.”

For Mahmoud, in mid-2016 he was looking for “a little bit of luck and good weather” to complete construction by year’s end and to put the new oil transportation highway in service in early 2017.

With memories of the Obama administration’s rejection of the Keystone XL project through northern states, ETP realized early on in its plans for Dakota Access that it needed broad-based support from stakeholders nationally. ETP decided the trade unions were really the organizations that could provide the type of leverage needed. The company sought out representatives in the Laborers International Union for North America (LiUNA), which was profiled separately in an issue of P&GJ for its community support of large infrastructure projects. LiUNA has taken on a proactive role around the nation in competing with activist opposition groups fighting against major energy infrastructure projects.

ETP in mid-2016 had about $14 billion at stake through mid-2017 in Dakota Access and two other major pipeline projects ongoing. “If you have the opposition groups, we decided to bring the labor forces to bear with these three major projects,” Mahmoud told his industry audience in May.

In the post-Keystone era, ETP and others are sensitive to footprints, rights-of-way, economic multipliers and the general fact that designing, permitting, constructing and restoring landscapes has become an ever-more intricate socio-economic, political and environmental engineering job just as much as the physical act of laying, connecting and burying the large-diameter steel pipe. Rights-of-way of 100-125-feet width in places were required, and paths through private rather than public lands were part of the endeavor.

On Dakota Access, ETP learned some “big lessons” about the agriculture sector which dominates the 1,100-mile-plus route, according to Mahmoud. Pipeline contractors must find ways to avoid interfering with farming operations, and in South Dakota, Iowa and Illinois that has meant altering heights of soil piles during construction, for example. Another accommodation involved lowering the depth of the pipe, which is 48 inches across all agricultural land, adding to project costs, but meeting the farmers’ needs.

The leak detection and remote control valve systems on the pipeline are “robust,” says Mahmoud, reiterating that ETP operates 71,000 miles of various energy pipelines across the nation and like other major pipe operators takes prides in focusing on reliability and safety. “It is all brand new pipe, all of the materials are of the highest quality, and every valve has remote activation on it,” he emphasizes.

“Some of the areas [being crossed] are pretty remote, so it’s much easier to control the pipelines remotely than have to send someone to drive an hour or two to get to a particular location,” says Mahmoud, adding that by the end of May with construction underway in all but Iowa, 96% of the rights-of-way was acquired without condemnation, although that would be necessary in some segments, mostly in Iowa.

“For 1,172 miles of right-of-way, we’re down to about 152 tracts of land still needing to be obtained out of 3,685 tracts,” he told his North Dakota audience, and that speaks to the original goal of building a pipeline with the “least amount of impacts possible.”

Bakken infrastructure experts, such as Kringstad, remember just a few years ago truck traffic carrying crude oil was straining local oil patch communities and the state’s then-overtaxed highway system. But since 2013, there has been a distinct downward trend in the amounts of Bakken supplies being moved via trucks, he notes, predicting that will continue.

“We’re back to 2011-12 volumes, and if you asked local people back then if they were happy with the truck transport, they would say this is still too much fluid being transported by truck,” Kringstad says. “So I expect pipeline volumes to continue ramping up and the barrels on the highways to decrease.” His Pipeline Authority data breaks out all of this county-by-county, indicating that crude oil gathering via pipelines has been rising “substantially,” particularly in the core production counties.

Because the same amounts of water need hauling as barrels of oil produced, the truck traffic will never disappear, says Kringstad. In the biggest oil-producing counties, while oil-gathering pipeline systems have grown, truck traffic has remained level, but eventually it will go down for hauling crude, but not necessarily water, he notes. “With the production growth in the play here, it’s always going to take more pipes; it simply would not be feasible to add more trucks.

“The Bakken is still a very young play, so we’re going to continue to see more infrastructure activity as it continues to mature,” Kringstad says. “This means more major pipeline systems and more potential market flexibility.” This is not just for oil, but for natural gas and natural gas liquids (NGL), he predicts, adding what the state’s chief oil/gas regulator, Lynn Helms, has dubbed the phenomenon as more “value-added” from Bakken production for the state.

Kringstad thinks for business development, North Dakota has seen many technology advancements for creating this value-added, and that should ramp up even more as commodity prices turn around, and some sustained growth returns to the Bakken. “There have been a lot of new players, new technologies, and companies, and people are taking serious looks at them to see if there are some good fits for them.”

In the midstream, the Bakken players have stayed pretty consistent throughout the downturn. Kringstad, who became head of the pipeline infrastructure unit in 2008 just as the Bakken boom was hitting its stride, is studying forecasts for oil and gas production in the state through 2035 that appear just as robust with oil hitting up to 1.7 million bpd, and gas and NGLs looking even stronger.

While it may not happen as rapidly as some in the industry think, infrastructure growth will be part of the Bakken’s long-term future. Kringstad anticipates there will be more projects like the Dakota Access line.

Comments