February 2015, Vol. 242, No. 2

Features

Southeast Asias Pipeline Challenges

Southeast Asia is considered one of the most problematic regions of the world in which to build pipelines since it encompasses active volcanos and thousands of islands. With a large land area of 4.46 million square kilometers and many countries, it is home to 616 million people, 150 million of whom have no access to electricity.

Currently, gas comes in third behind coal and hydro as a source of the region’s electricity generation. However, it is a dynamic region with Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) economies forecast to triple in size between 2013 and 2035, and demand for energy expected to rise by over 80%.

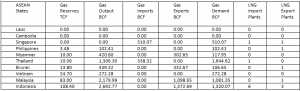

ASEAN country’s gas reserves stand at 3.5% of the world’s total endowment, according to Oil & Gas Journal, with Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand the largest gas producers and markets (Table 1).

In 2012, the International Energy Administration (IEA) reported that ASEAN gas production totaled 202 Bcm. With domestic demand of 149 Bcm, the difference is available for export. According to the EIA, Indonesia is the world’s 11th-largest natural gas producer followed closely by Malaysia in 14th place. In 2013, the region accounted for almost 25% of the world’s LNG liquefaction capacity at 89 Bcm yearly.

Indonesia, Malaysia, Myanmar and Brunei dominate the region’s gas exports to China, Taiwan, South Korea and Japan. Exports of LNG by tanker predominate due to the absence of an intraregional pipeline system and inadequate national pipeline networks. The exception being Myanmar’s pipeline, which tranships of Middle Eastern gas to China.

Much of the region is dependent on remote gas fields where gas has to be collected, gasified and shipped by sea to regasification plants close to major cities, for onward delivery to customers. In the case of a poor gas market, such as the Philippines, LNG imports from Malaysia are regasified and piped directly to power stations.

To help meet rising domestic demand, national energy companies plan to construct 3,682 km of gas pipelines to add to the existing 19,800 km of pipelines (Table 2).

Table 2: Proposed Gas Pipelines 2014 Source: ASEAN, Enipedia data

Trans Asean Gas Pipeline System

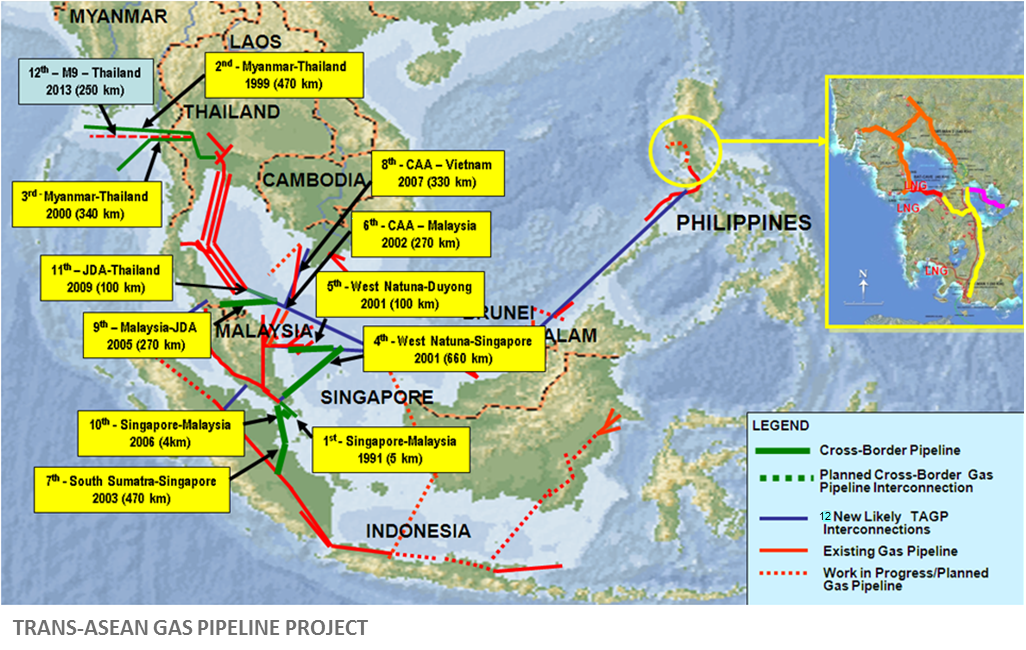

One project stands out: The Trans ASEAN Gas Pipeline (TAGPS), designed to create a regionally integrated gas market by interconnecting existing and planned gas pipelines of member states. Due for completion by 2020, it is less than half ready, with only 12 cross-border gas pipelines in place, transporting over 3 Bcfd along 3,169 km of pipes.

However, further construction obstacles face operators, ranging from differences in market structures, nationalist sentiment and, above all, economic rationale. For most ASEAN countries – Thailand, Vietnam, Philippines, Peninsula Malaysia and most of Indonesia – domestic gas now fails to meet domestic demand.

“For these countries imported LNG now sets the opportunity cost of natural gas,” said Thomas Parkinson, a founding partner of The Lantau Group. “Since the cost of imported LNG would be more or less identical across different countries, this suggests that there is virtually no economic rational to such pipelines.”

A snapshot of the main pipeline users in the region:

Indonesia – State-owned Perusahaan Gas Negara (PGN) controls and operates over 3,600 km of natural gas transmission and distribution pipelines. However, domestic distribution infrastructure is almost non-existent outside of Java and Sumatra.

PGN began operating the South Sumatra-West Java pipeline, which bypasses the Krakatoa volcano in 2008, providing an important link between the gas-producing region of South Sumatra and the densely populated market of West Java. A current major project, the Trans-Java gas pipeline, totaling 682 km, could be in operation in 2015 and is designed to deliver 200 million tons of gas a year to customers in eastern Java and Bali from Kalimantan gas fields.

Since liberalization in 2002, private companies have begun operating pipelines. For example, PT Transportasi Gas Indonesia operates two gas pipelines radiating from the South Sumatran gas fields of Grissik. The first is an important domestic transmission pipeline providing gas to two power stations as well as Chevron’s Duri oil fields. The second is the cross-border pipeline linking Grissik to Singapore.

Vietnam – The nation plans to develop its natural gas fields, estimated to be the fourth-largest in East Asia, following ExxonMobil’s gas discoveries in 2012. Should agreement be reached, gas would be piped from the offshore field to a processing station to provide feedstock for a planned 2,500-MW generating plant.

State-owned PetroVietnam operates 955 km of pipelines linking major cities directly with offshore gas fields. It intends to construct a new gas pipeline, the $1.3 billion Nam Con Son 2 Vietnam, to carry 7 million metric tons of gas a year from an offshore gas field in the Gulf of Thailand to Ho Chi Minh City.

Malaysia – State-owned Petronas operates 6,439 km of gas pipelines linking offshore gas fields in the South China Seas with major cities such as Kuala Lumpur and Putra Jaya. This network, known as the Peninsula Gas Utilisation Project, delivers gas to neighboring Singapore and Thailand. The just-completed Sabah Sarawak Gas Pipeline delivers gas to the Libuan LNG Export terminal and brings gas to communities in eastern Malaysia from offshore gas fields in the South China Seas.

Singapore – Gas from its neighbors meets 84% of the city-state’s power needs. Singapore is directly connected by four cross-border pipelines to offshore gas fields in both the Malaysian and Indonesian parts of the South China Seas as well as Sumatra.

The city-state is focused on developing a LNG hub based on its first 9 million tons per year LNG import, and an export terminal coming online in 2013 with another planned. According to Reuters, Singapore has prevented its four pipeline gas importers from signing new contracts until 2018, or when demand for LNG shipped in by BG Group Plc, hits 3 million tons per year, whichever is earlier.

Moreover, according to energy consultant David Ledesma, of South-Court Ltd, “Singapore is building LNG terminals as insurance, as it is expected that Indonesia and Malaysia will reduce supplies when the contracts expire in the early 2020s, so to supply their domestic markets with the gas.”

Future

Domestic offshore gas development across the ASEAN region and particularly in Vietnam, will probably increase, and with it construction of pipelines to connect offshore fields with onshore domestic markets.

However, given that the marginal cost of gas-fired power will be tied to LNG prices, which are higher than coal, this suggests “There may not be as much need to build out gas delivery networks as might be suggested by gas demand forecasts,” Parkinson said.

Indeed, as Peter McCawley, visiting Fellow, Indonesia Project, Australian National University pointed out, “The priority is to strengthen power networks, most likely with coal, before constructing gas pipelines.”

As for completion of the Trans-ASEAN pipeline, the reality is that each country values its sovereignty and considers only its own demand and resources. Floating LNG liquefaction and transport is now a serious alternative to pipeline connections, leaving most new gas pipeline construction aimed at local distribution between LNG terminals and nearby cities.

Comments