September 2014, Vol. 241, No. 9

Features

Mexicos Energy Reform: Ending The Inertia

A key aspect in understanding the troubles of Mexico’s oil and gas sector is the federal government’s high budget dependence on the revenues of the National Oil Company (NOC) Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex).

Through heavy taxation the company has been recently funding 32-35% of the federal government’s expenses and as a result has been left with a limited budget for any significant reinvestment strategy. As a consequence, in the last 10 years Pemex has faced increasing difficulty in both managing a decline of its total production and successfully exploring and developing additional hydrocarbon reserves.

In addition to these constraints the subject of oil in Mexico is highly ideological and political. Any topic related to hydrocarbons is connected to a nationalistic interpretation based on the 1938 expropriation. The Mexican constitution incorporates these principles by securing state exclusivity in managing the hydrocarbon resources.

Allowing private participation in the sector in schemes that differ from service contracts would require a constitutional change. Due to strong public sentiment, any attempt to reform the sector has entailed significant political challenge.

Other administrations have made efforts to reform specific parts of the hydrocarbon sector but successes have been limited. Whenever private companies have been allowed to enter the sector it has usually been either through a special agreement or a single subcomponent of the value chain. Some of the most liberal cases of these changes have amounted to the creation of service contracts with performance indicators or private participation in the midstream sector for natural gas.

The most groundbreaking aspect of the energy reform is the change in the constitution that will allow private companies to participate in exploration and production activities under specific contracting schemes. Nonetheless, it is explicitly stated that the resources will always be under the ownership of the nation.

Another recent attempt at reforming the sector occurred in 2008 during the administration of President Felipe Calderón. After a series of congressional debates and intense negotiations an approved bill contained mainly institutional changes and modifications to secondary laws. These sought to relieve Pemex of some fiscal burden and provide more flexibility in designing service contracts that could account for the contractor’s performance. Judging by the number of operators that showed interest, this reform held only limited success.

The most recently approved reform is more ambitious than the original proposal sent by President Peña Nieto last August or anything done in the past. Nevertheless, it is still extremely general concerning actual terms of participation and does not contain information on which type of contract will apply to which type of project.

In other words, industry observers and participants will have to wait for the so-called secondary laws that will frame the fiscal terms for the new contracts. This additional information will allow for a more rigorous test in assessing the effectiveness of the 2013 energy reform. When this fine print will be drafted and voted has not been decided, but the second half of 2014 could be viewed as the best-case scenario.

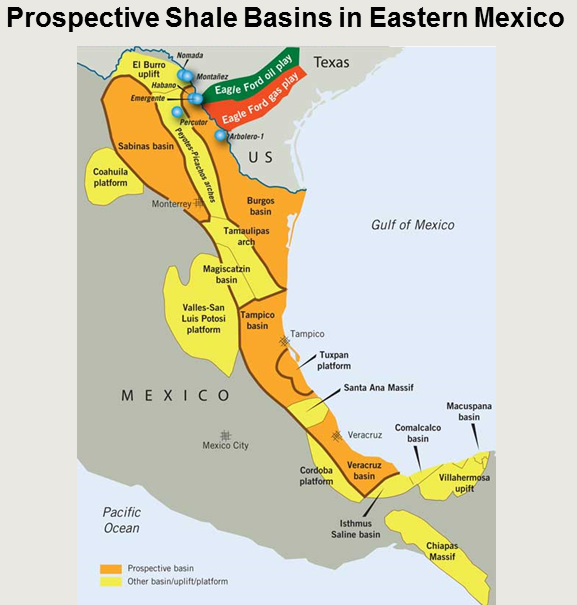

Progress toward the reforms began in August 2012 when the executive branch of the Mexican government sent Congress a proposal to reform the energy sector. Concerning oil and gas, it argued the bulk of the country’s remaining hydrocarbon reserves are located in challenging areas from both a geological and engineering perspective. As a consequence, recovery requires sophisticated and expensive technology.

Although Pemex has ample expertise in shallow waters, the company does not have the expertise to enter more complex projects located in offshore deep waters or onshore shale plays. Furthermore, the proposal established that it would be imprudent from a business standpoint to let Pemex assume the risk of such projects.

It followed that it would be necessary to let Pemex to form joint associations with other oil and gas companies for the riskiest ventures, as well as to let the company contract with operators for other conventional and unconventional projects. This in turn made the case for changing the articles in the constitution that would allow private companies to participate in the exploration and production of hydrocarbons.

The original proposal, backed by the ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), only considered a profit-sharing contract. The approved reform includes the additional options of production-sharing contracts and licenses, which are generally considered much more attractive. These additions were put forward by the right-wing National Action Party (PAN). From the beginning, the left-wing Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) never favored changing the constitution. When the PRD decided to leave the institutional channels for negotiation, declaring it would protest in the streets, PRI gave in to PAN’s demands for broader reform.

PRD indicated plans for organizing a referendum in 2015, seeking to invalidate the approved reform. The party presented the case to the Supreme Court, arguing that the right of citizens to decide key national issues should be guaranteed. It is now up to the Supreme Court whether to allow such a referendum.

The approved reform establishes contracting options for hydrocarbon exploration and production must include service contracts, profit- or production-sharing contracts, and licenses. However, the changed law does not specify which type of contract will be applicable to the different types of hydrocarbon exploration and production.

Furthermore, the inclusion of the words “among others” in the bill’s text may leave the door open for more tailored contracts that give the state flexibility to include the right fiscal incentives for private companies. Similarly, this could lead to inconsistency and a lack of transparency in designing contracts, but then this all depends on the accuracy of the secondary legislation.

Nonetheless, Pemex’s necessities in a way indicate the opportunities for private investment. Deepwater, shale and even shallow water areas can benefit from different combinations of technology transfer, capital expenditure in exploration and development, and managerial expertise. For instance, Mexico’s deepwater prospective area in the Gulf of Mexico is considered under-explored. In this case, the licenses could be the right type of contract to attract necessary capital while also compensating for a high exploratory risk.

Profit and production-sharing contracts will most likely be used for areas where the state and Pemex consider that capital has already been successfully invested but a partnership can still be beneficial. For example, this could apply to some areas in the geologically challenging Chicontepec Play, which holds about 40% of Mexico’s 3P reserves, and where Pemex has been extremely active during the last decade.

It seems fair to assume the first bidding round for private investors will include production and profit-sharing contracts just to test the waters. The licenses will remain a politically sensitive and costly issue and might, therefore, be more difficult to implement in an initial round. Furthermore, in subsequent rounds the Mexican state could benefit from the interaction, feedback and results of any previous round.

In the end, service contracts will remain the preferred scheme for oil and gas services companies, and some may also incorporate a risk or performance-related adjustment. A good example of these modified service contracts are those created after the 2008 energy reform. They were designed for use in rounds offering offshore mature fields and some areas in the onshore Chicontepec Play.

According to Pemex’s officials, the government is scheduled to make its Round Zero decisions by Sept. 17. As is the case in these initial rounds, preferential treatment is given to the NOC concerning which existing and prospective projects they would like to keep out of future offerings.

This is important not only because it will determine what will be available for private bidding but also because it will introduce a far more serious role for the existing regulatory agency, the National Commission of Hydrocarbons (CNH). Along with the Energy Ministry, the CNH will be directly in charge of approving Pemex’s round-zero proposal.

Still, the reform is fairly general in offering a mechanism making the regulatory agency more autonomous from an institutional and financial point of view. As in the case of new contracts terms, the details will be determined in future secondary laws.

Corruption and a lack of transparency in the Mexican oil and gas sector is not only an important issue to opponents of the reform in government and business circles, but also to the Mexican civil society in general. Again, how effective the new regulations and improved regulators will be is still an open question.

Furthermore, modernizing Pemex would require more than just lowering its fiscal burden or giving the company the opportunity to associate with experienced oil and gas companies. The reform states that Pemex’s status will be changed from a decentralized public organism to a productive public company with the goal of greater autonomy – how that will be achieved has yet to be explained.

Pemex is a company with severe operational and financial inefficiencies in its refining and petrochemical subsidiaries, and many agree the company’s excess labor is an issue that needs a prompt solution. In addressing this point, the powerful Pemex workers’ union was stripped of its advisory board seats during the reform negotiations. Arguably, this was a positive step toward allowing the board to make decisions on restructuring the company’s subsidiaries.

NOCs As Powerful Tools

As demonstrated by Norway’s Statoil, Brazil’s Petrobras and others, a competitive NOC can be a powerful tool, expanding the state’s reach beyond its own domestic resources. Getting this right will, therefore, be a crucial test for the approved reform.

Private participation in Mexico’s energy sector is expected to bring the necessary injection of capital and technology to unlock vast hydrocarbon resources. What now follows is the modification of the related secondary laws. Those only require a simple majority in Congress to be approved. As such, PRI’s political maneuver, as well as the policy directives of the Energy Ministry, will be a factor.

A crucial test will be how international oil companies (IOCs) react when the first new opportunities are offered. This, of course, will depend to a great extent on what they are offered. In any case, there is a long way to go before the approved reform translates in actual new production or has a significant effect on the wider Mexican economy through lower energy prices.

In summary, there is still a lot to be clarified in the secondary legislation, but for the moment this reform seems to bring the opportunity for ending an inertia that has lasted longer than necessary. The most important point is that the passage of this bill removes the barrier of the constitution from a wide range of future reforms, allowing Mexico’s energy sector to adapt to prevailing conditions in the future.

Comments