August 2014, Vol. 241, No. 8

Features

Houston: Undisputed Center Of The Oil-Gas Renaissance

That Houston is the hub of the oil and gas industry has been evident for decades. What is less obvious, though, are some of the unusual advantages the 600-square-mile Gulf Coast city has established that will keep its position of dominance secure for years to come.

In some regards, Houston’s enviable position in the energy sector might have seemed like a longshot on the surface not that many years ago. After all, little drilling is done near the metropolitan area of 6 million residents, making federal Bureau of Labor Statistics numbers that show almost 40% of Texas’ oil and gas employees reside in the Houston metropolitan area a little difficult to fathom at first glance.

There is a simple explanation, however, according to well-known regional economics researcher and forecaster Bill Gilmer. Houston, like other areas that dominate industries, such as Wall Street, Detroit and San Jose (high-technology), has captured what he called the heart of its industry.

“When you talk about these big clusters, or industry hubs, what is established after a while is essentially a concentration of expertise,” said Gilmer. “These people are obviously not drilling, but all of the executive leadership, as well as all the technical talent, is found in Houston.”

As director of the University of Houston’s Bauer Institute for Regional Forecasting, Gilmer sees Houston as having developed into something more akin to two related energy clusters – upstream, with its lock on oil service companies, and downstream, which extends along the petrochemical crescent, running from Corpus Christi, through Houston on over to New Orleans and Baton Rouge.

“It gives Houston a very nice balance the same way integrated oil companies have this nice balance between upstream and downstream,” Gilmer said. “The Houston area really does ultimately act like an integrated oil company. The balanced part is not so much with the profits, but from the capital investments that shift from upstream to downstream when the die turns.”

When clusters form, as has been the case in Houston, suppliers follow to be close to the action. According to Gilmer, this creates “a sort of knowledge loop.” As an example, he cited the size of the Geophysical Society of Houston, which boasts 2,000 members.

“If you advertise for a geophysicist in Philadelphia or Chicago, you would be lucky to get a response, but a lot of people in Houston can answer that ad,” Gilmer said, adding the energy-related specialized talent among reservoir and chemical engineers, and geologists runs equally as deep in the city.

“It doesn’t matter whether you are Bechtel or Parsons, even if your headquarters may be elsewhere, the division that does continuous process engineering for petrochemicals and refining and pipelines and flow is headquartered in Houston,” he said.

With exploration and drilling expenditures growing at a time when the labor market is extremely tight, particularly upstream, one factor working to increase the size of the skilled labor market in Houston is wages. Annual earnings for geologists, geophysicists and executive talent within the cluster averages $300,000. In 2011, the typical upstream job in Houston paid $140,000.

“How are you going to get that talent to relocate to California? Not just because it’s more expensive there, but because it’s going to be very expensive to operate there,” Gilmer said.

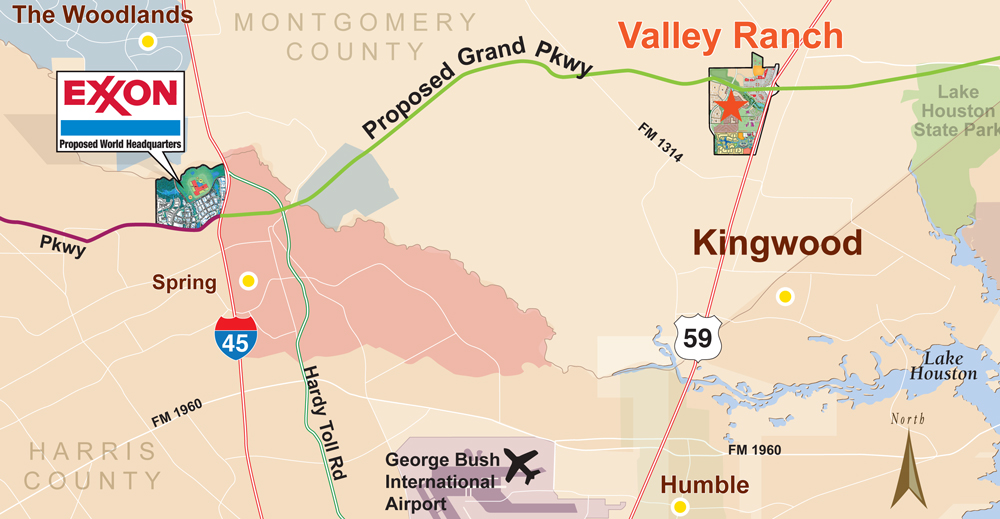

The competition for top-level, skilled employees has led companies not only to move operations to Houston, but also build campuses in places like the rapidly growing Woodlands and Katy suburbs. This is designed to attract workers with the added perk of not having to drive all the way downtown.

ExxonMobil is building a new complex on 385 acres near The Woodlands that will house 10,000 employees and is expected to open in 2015, while BHP Billiton leased a 30-story office tower to be built within city limits to accommodate its expanding shale business and future growth. A separate two-tower campus at that location will hold 2,000 employees.

Additionally, Chevron Corp. signed an agreement recently to purchase 103 acres along a newly opened section of the Grand Parkway in Katy. The acquisition, expected to close in the third quarter, will be used for “future research and development facilities flexibility,” the company said.

While the upstream growth has surged to the west of the city for years – along Beltway 8 and what has come to be called the Energy Corridor along Interstate 10 – recently there has been a serious ramp-up to the east of Houston as well.

ExxonMobil Chemical, on June 23, began construction of a multibillion-dollar ethane cracker at its Baytown complex, which will have a capacity of 1.5 million tons per year and provide ethylene feedstock for downstream chemical processing, including processing at two new 650,000-tons-per-year, high-performance polyethylene lines at the company’s Mont Belvieu plastics plant.

Meanwhile, Dow Chemical Company will begin construction shortly on a world-scale ethylene production facility in Freeport, expected to be online in the first half of 2017.

“Now there is a race to tie up skills and crafts [workforce] on the east side of town,” Gilmer said. “It’s going to be completely different – blue collar adds a completely different flavor to the expansion.”

If anything, Houston has strengthened its grip on oilfield services as well, led by Schlumberger, Weatherford, Halliburton and Baker Hughes, which support their share of the market with billions of dollars spent on research and development each year. While all but Baker Hughes maintains overseas headquarters for tax purposes, each has an employment base firmly entrenched in Houston.

“You could probably make an argument that London is more of a rival to Wall Street as the global financial hub than you could say anyplace rivals Houston in energy at this point,” Gilmer said. “For anything sophisticated, you are going to call one of those four companies.”

Early Days

The event that got things rolling for Houston took place in 1901, about 85 miles northeast of the city in Beaumont, where the first great Spindletop oil gusher came in. Texaco, Gulf Oil and Sun Oil (Sunoco), all formed in the area and brought exploration efforts to the Humble oil fields outside of Houston within three years.

As a result, Houston with its nearby major rail center and advanced telegraphy services became the center of the new Texas oil industry. In 1914, the Houston Ship Channel opened and a concentration of refineries began to evolve in the Southwest Texas, spreading throughout the state by 1930.

By the end of World War II, the city and its surrounding area had become industrialized by a boom that created the greatest concentration of petrochemical plants and refineries in the world. For Houston, however, the best was yet to come.

“This boom is even bigger than 1982 by a factor of four, five or six, depending on where you actually count,” Gilmer said, calling technological innovations, such as horizontal drilling and fracturing the biggest economic drivers the region has ever seen.

That these technologies, originally developed in large part by the late George Mitchell for natural gas recovery, have been adapted to drill for oil simply enhanced the industry’s position.

“Obviously, the price of oil has stayed above $100 a barrel, and it’s an international commodity,” Gilmer said. “If we had stayed with just natural gas, we’d have been out of luck right now.”

That Texas has a relatively small social safety net, which comes with low taxes and a business-friendly environment, has made relocating to Houston even more attractive for oil and gas companies.

“Texas would argue it offers a ladder up for its people and allows for cheaper housing, while other states [with larger social services programs] would say they protect the lessers within the population,” Gilmer said. “However you may think about the tradeoff, you are giving up jobs when you adopt a bigger social safety net and higher taxes.”

Finance Rebounds

Despite a rocky history that culminated in the 1980s failures of Texas Commerce Bank, which basically invented spending on reserves in the ground, and First City Bank, the premiere vendor for the oilfield services industry, energy lending has rebounded in Houston.

Wells Fargo, which may be the largest energy lender in the United States, has established its reputation with a major presence in Houston. Additionally, an ever-growing number of foreign banks operate offices in the metropolitan area, accounting for one of the largest concentrations of foreign banks in the United States.

“Those banks are not here doing car loans,” said Gilmer, who served as vice president of the El Paso Branch of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas until 2012. “They are here putting together big syndications with Fortune 500 companies to lend money for multibillion-dollar deals.”

At the center of the city’s oil-related activities are large, integrated companies such as Chevron, Shell, BP and ExxonMobil, along with independents, including EOG, Noble, Anadarko and Apache. A notable array of foreign companies, including Statoil, Petrobras, BG and BHP Billiton have joined their ranks in recent years. These are the companies that decide where to drill, what financing to take on and which oil service companies to hire.

Adding to these impressive ranks after each recent downturn in the industry have been more E&P companies from Tulsa, Midland and elsewhere that have relocated divisions or entire companies to Houston.

End In Sight?

Since 2009, when Houston lost 100,000 jobs to plummeting oil prices, the city’s employment numbers have grown substantially, increasing at more than twice the national rate, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Leading the city’s boom, according to Gilmer, has been the unprecedented growth of E&P spending, which has increased by a factor of four to $279.1 billion since 2003.

So when is this unprecedented growth likely to run its course?

“I would say it all ends when the price of oil goes under $65 or $70 a barrel,” Gilmer said, referring to the price needed to sustain drilling in oil shale and deep water. “If you look at downturns that have happened in the past – the tech crunch [2000], the American financial crisis [2008] – I don’t know anyone that had those in their forecast or five-year outlook.”

Despite the importance of the E&P sector to the Houston economy, he said he feels the city has diversified significantly from the 1980s and 1990s, and that the volatility of the local economy that began in the 1970s has ended.

“What you should have in your business plan is something to make sure you can survive the unforeseen, because the price will go down at some point,” Gilmer said. “I think Houston and these businesses have gotten experienced and sophisticated enough to understand the issues.”

Comments