April 2014, Vol. 241 No. 4

Features

Massive Pipeline Investment Hot Topic At Energy Conference

Huge investments will be required in pipeline infrastructure, especially in North America, according to a consensus of speakers at the 2014 IHS CERAWeek conference in Houston March 3-7.

Russ Girling, CEO of TransCanada, said, “We have a lot of opportunity in front of us, probably more opportunity than I’ve ever seen in my 30-year career.”

Girling cited an IEA estimate that between now and 2035, the United States, Canada, and Mexico will need $6 trillion worth of energy infrastructure work, including spending on oil, gas and power resources.

“$2.5 trillion of that $6 trillion is going to be spent in oil infrastructure here in North America,” he said. “That’s more than anyplace else in the world, which is probably unexpected, given that this is a continent that has seen the free flow of oil through the continent for decades.”

The need for such a staggering amount of investment puts the furor over the Keystone XL approval into worrisome perspective. According to Girling, Keystone XL is a $5.4 billion project – large considered on its own merits – but representing less than 1% of the total estimated spending needed.

Spectra CEO Greg Ebel cited an IHS and API study on the increasing investments needed which showed an average of $75 billion a year worth of infrastructure replacement over the near-term future. He discussed Spectra’s recent completion of a gas pipeline into New York City as a major success, though he quoted a price of $1.2 billion for 12 miles of installed pipe.

Ebel also talked about the proposed expansion of Spectra’s Algonquin system into Boston and the general difficulty of getting pipelines into the Northeast, where demand is high and rising. Gas prices remain low enough to attract heating and power generation customers, but the disinclination of power generators to subscribe to pipeline contracts has meant no new construction can be financed with traditional open season methods.

“I understand why power producers aren’t signing up,” for dedicated pipeline service, Ebel said. “There’s no economic incentive to do that. Infrastructure does cost money,” and either producers or consumers eventually have to pay for it.

Balancing who pays for what and how is one of the challenges for the market in the near term, but an effort in the affected states to find a way to finance construction with a charge to ratepayers has shown promise. Ebel emphasized that the benefits would outweigh the difficulties and the cost, referencing the drop in gas prices for New York customers from 64% higher than eastern Pennsylvania’s in November 2012 to only 13% in November 2013 when Spectra’s new pipeline came online.

“There’s an economic cost to infrastructure,” he said. “It is far lower than the economic benefit of infrastructure.”

Steve Wuori, strategic advisor to the office of the CEO at Enbridge, spoke about markets on the supply side of that imbalance, especially in Western Canada and the Bakken. “Part of what pipeline projects are designed to do is to help stabilize, not eliminate, the differential. There always needs to be a lot of transportation costs built into the differential, but the differentials especially for Canadian heavy oil have gone far beyond transportation costs. Which has meant there needs to be more transportation.”

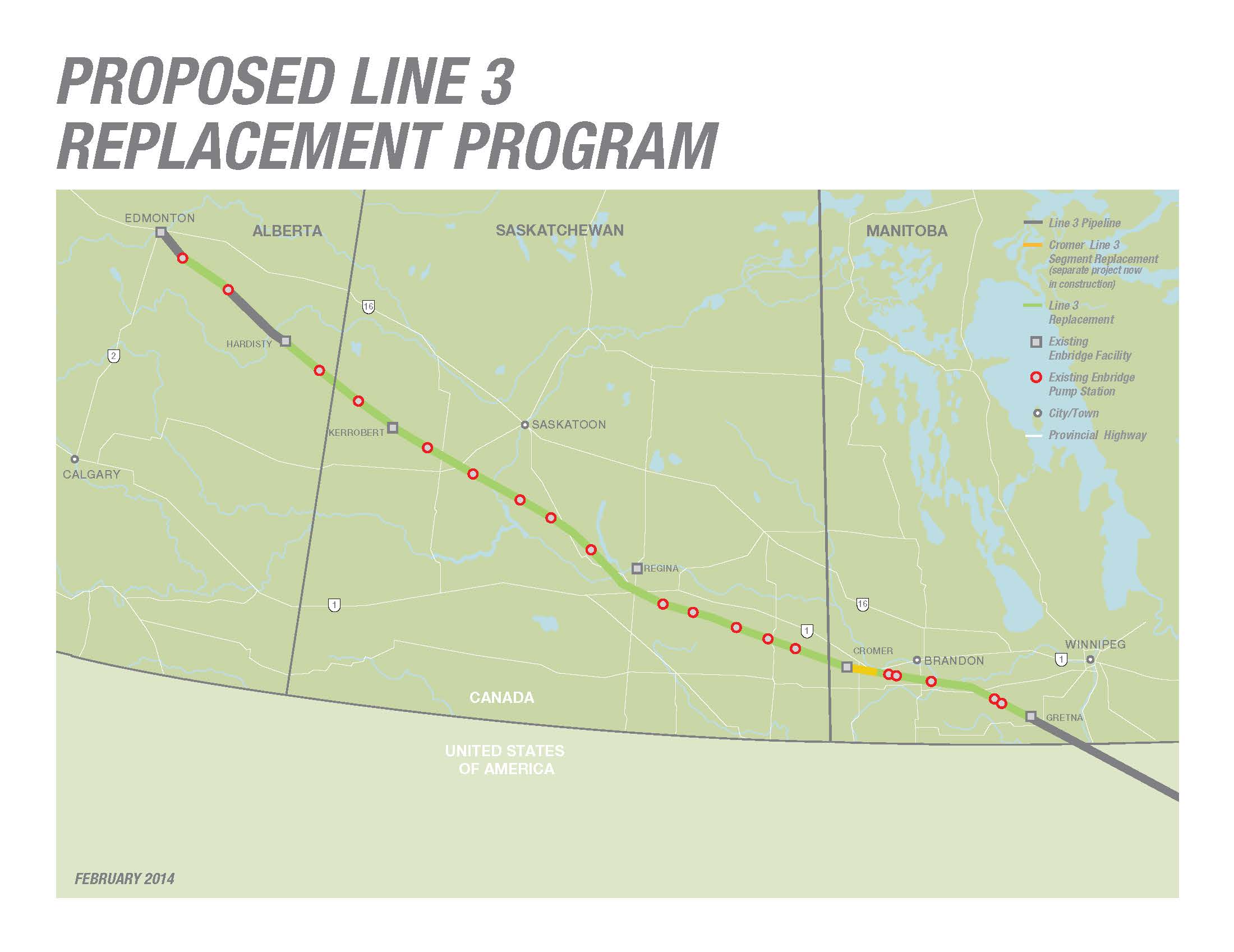

Wuori mentioned pipeline and rail projects in various stages of approval and construction in the region. Enbridge plans a $7 billion replacement of its existing Line 3 pipeline that would almost double its capacity, to 760,000 bpd. The expansion would run from Hardisty, AB to Superior, WI, but because it replaces an existing line would not need U.S. State department approval.

Solving price differentials is “a very important factor for investment decisions,” Wuori said. “But to this point it has not curtailed any investment decisions from being made because there is a confidence that these differentials will become manageable or predictable.”

He also discussed his changing view of crude-by-rail transport. “My view has certainly evolved; I had to get over my own bias. That was that our system from 1949-50 was built to take oil off trains and put it on to a pipeline.”

Now, he said, Enbridge thinks “rail will probably always have a place in [oil transport]. There are some markets that will never be served by a crude oil pipeline.” Specifically, California, Philadelphia, and Washington state, while good destinations for Bakken oil in particular, were unlikely to be targeted as the end point of a pipeline.

“I think there are a lot of ways that pipe and rail can complement each other in making sure we get to the most markets,” Wuori said. “You’re actually going to see ‘ride the pipe as far as you can and then get on rail to final market.’ Sometimes you might see ‘rail it to a pipe point and then get on pipe to final market.’ There could be more of that and as I look forward that could be very positive. I think it is here to stay.”

The key to remember, Wuori said, is a basic truth of transit: “Commodities will always follow the easiest path to the highest price.”

Those filling the pipelines offered perspective as well. Rick Bott, president and COO of Continental Resources, told listeners that while he expected the long-term takeaway issues for the Bakken region were resolved and production would stay below capacity at least through 2023, the midstream sector of the industry was among the hardest to convince that the volume of resources in the play was worth the investment.

“Five or six years ago you couldn’t find anybody to take your oil from the Bakken. We had seriously steep discounts. The best we could do was sell our crude to a middleman at the railhead.” There light Bakken crude was blended with heavy Canadian crude to match WTI specifications, and the middleman made large profits selling to refineries.

“After the midstream guys started understanding the size potential, they started coming with investment a little bit here and there,” Bott said. “Pipelines took off. Rail caught up a little after that.”

Aside from pipeline projects already underway, Bott said Bakken producers are now looking for first-mile delivery capability and a way to sell associated gas. He estimated gathering systems could offer him an additional $1.50 in cost savings, while 35% of associated gas across North Dakota was being flared in what Continental saw as “value being lost.” He cited a 10% flaring ratio for his company.

Now Bott sees Bakken producers needing to win partners further downstream, in refineries and Washington, DC. “The biggest macro challenge left is: how does the rest of the country benefit from what the midcontinent is benefiting from in terms of the quality of crude?” he asked. A more free-flowing distribution of the resources could help. “If we can figure a way to get it to the eastern and western markets by pipe and lower costs, I think that’s going to be good.”

Ongoing questions, including whether U.S. oil exports might be permitted, whether tight oil plays’ steep decline rates would scare off investors, and the increasing public interest in various aspects of fossil fuel production and transportation were all worthy of optimistic outlook from the industry, Bott said. In addition to the abundance of high-quality crude in the Bakken, he professed faith in the ingenuity of the market.

“No matter where we’ve found them in the past 150 years, our industry has always overcome bottlenecks in the arbitrage opportunity with technology and investment, and there’s been no difference here.”

Comments