July 2013, Vol. 240 No. 7

Features

California Dreaming? Could The Monterey Be Road To Oil Future?

“I think there is lots of opportunity. It is whether or not the economics can line up with the technology to get it out of the ground.” – oil executive in Bakersfield

Between federal numbers crunchers, and a university and think tank-based report that surfaced earlier this year, California’s venerable Monterey Shale is stirring renewed dreams of California gold – black gold in the form of heavy crude.

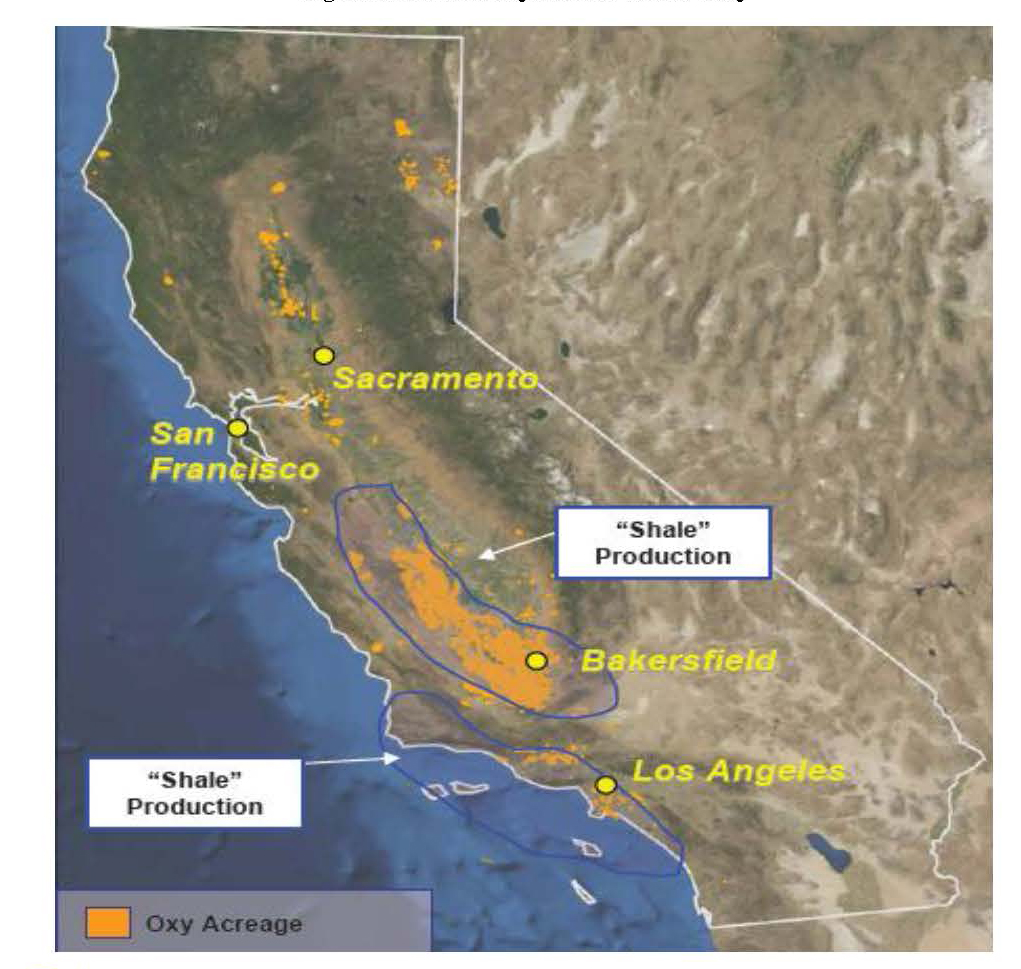

While there remains conjecture about how much attraction the service sector is finding in the Monterey, it isn’t like there aren’t already some big names among exploration and production (E&P) majors and independents in the chase. The likes of Occidental Petroleum Corp., Chevron Corp., Aera Energy LLC, Venoco Inc. Plains E&P Co. and Berry Petroleum have stakes in and around the play.

A federal Energy Information Administration (EIA) report last year did nothing to quiet the discussion, assigning a long-range potential of more than 15 billion bbl of oil lying deep in the Monterey Shale, which underlies all of California’s most productive oil fields (Elk Hills, Belridge and Midway-Sunset). Some analysts believe it extends far offshore in addition to covering the deep core of the southern and central valley region of the state.

“There is good reason for interest in the Monterey,” say the authors of “The Monterey Shale and California’s Economic Future,” a research study from three schools at the University of Southern California.

However, the study cautions, it is not quite so simple.

“Oil cannot be extracted from deep shale formations like Monterey through the use of conventional oil wells that dot California landscapes. Rather, advanced oil extraction technologies, like hydraulic fracturing (fracking) and horizontal drilling are required.”

One industry insider said the USC study has “added a new dimension” to the ongoing discussions about the Monterey, particularly for oil and gas people, located in the great central valley, who are yearning for some economic stimulus.

Some of the old pros in the fracking equipment side of the business, however, are somewhat positive about the chances of success, using some of the same drilling methods from the Bakken Shale in North Dakota to help break loose the Monterey. But skeptics abound, too.

A private equity investment analyst took some rather large swipes at the Monterey last year, concluding, “we don’t expect a ‘Bakken Boom’ to strike the San Joaquin Valley” in an AllianceBernstein report published by Bob Brackett in mid-2012. The title for Brackett’s analysis tells much of the story: “The Mystery of the Missing Monterey Shale.”

But, for this writer, the report itself has proved to be a mystery of sorts. Neither AllianceBernstein nor Brackett responded to repeated requests for a copy, which the New York City-based asset management firm treats as proprietary and for its clients alone, although the tome has been quoted and written about in general interest and industry publications.

One of the main points where divergence of opinion begins is the question of whether Monterey’s mother lode can be effectively recovered in the near future. One veteran state oil and gas industry official said, “I think that is what folks are trying to work out from a technical standpoint right now,” he said, adding that the metrics show different possibilities, depending on what your inherent interests and expectations are for the Monterey.

A veteran San Joaquin Valley oil industry journalist, John Cox, with the Bakersfield Californian, has reviewed Brackett’s work and summarized its reasoning for the Monterey’s under-performance thus far as a combination of an abundance of natural faults, low reservoir pressures and a geological profile that is not conducive to fracking. Cox buys into the region’s varying, rather complex geology, but he also leaves room for the possibility that veteran petroleum engineers locally may still “figure out” some things, and that is why there are still reports that firms like Hess have renewed interest in the Bakersfield area, among others, in the central valley.

In announcing plans for a $110 million national energy research center in Oklahoma in March, GE CEO Jeff Immelt touted the potential in unconventional resources, which means growth for technology, equipment and service sector firms.

“Unconventional resources and shale gas in particular may be one of the biggest productivity drivers in our lifetime,” Immelt said. “At GE, we see a tremendous opportunity in the oil/gas space. Since 2007, we have invested $11 billion to build broad technical capabilities.”

It is this type of commitment to advancements and investment that the Monterey is counting on, supporters and critics would agree.

A Los Angeles-based geologist, Donald Clarke, was quoted late last year in a publication of the American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG) as saying, historically, interest in the Monterey has run in 20-year cycles, and it has been about that long since the last widespread interest. It has been kicked off again by the 82-page EIA report, “Review of Emerging Resources: U.S. Shale Gas and Shale Oil Plays” that gives Monterey enormous, albeit, still unfulfilled potential.

“The Monterey, to be exploited properly, will have to have a lot better understanding of what is going on,” said Clarke, noting the California formation is much thicker than the Bakken or the Marcellus. “It is very tall in many places, so there needs to be a lot of science done. The Monterey of the future is going to have to be an unconventional play. It is not going to be the typical anticline, or synclines or fractures of the past.”

There has been a lot of work done in the Monterey, but almost all of it is in a conventional manner, and that is not the future.

“The future of the Monterey is in the unconventional. Now you’re going to go into a layer that is saturated with oil and you’re going to frack,” Clarke said. “It’s going to have to break and you propagate your fracture a certain distance, then you have to keep that fracture open, and then you can produce that oil.”

Issues like rock properties and deformations that keep geologists busy are all part of the greater understanding needed in the Monterey, he said. Industry and researchers at California State University, Long Beach and at USC, are studying the Monterey to add to this understanding.

“Companies are keeping their secrets close to their chests,” Clarke said. “But there is a logical answer to this and it is going to take a basin-wide study to provide the answers.”

Clarke told that AAPG audience he thinks Monterey development will follow the same pattern as most other U.S. shale plays in which a single company eventually unlocks the right approach to drilling, fracking and production. For the Monterey, based on its land interest and activity so far, that could end up being Denver-based Venoco Inc. or Los Angeles-based California oil/gas giant, Occidental Petroleum Corp., whose senior executives in recent years have talked about the Monterey without much hype on quarterly earnings calls.

“Significant” positions in California, as well as the Bakken Shale and Permian Basin, are cited as why in the past couple of years Occidental’s U.S. oil/gas production has become 60% of its worldwide output, according to an analysis earlier this year from Standard & Poor’s Ratings Services (S&P). In assigning a “stable” outlook to Oxy’s future, S&P said the E&P will likely focus more on oil-related drilling activity this year.

“Strategically, the company focuses on large, complex development of mature fields using advanced recovery techniques,” it noted, citing California and the Permian reserves as strengthening the company’s credit quality.

While touting Southern California’s Los Angeles-Long Beach Basin as acre-for-acre one of the world’s most productive oil areas historically, Clarke told AAPG that figuring out the Monterey could be a “very expensive, very risky project. There are a lot of places it can get knocked down.”

Noting that the Monterey is more than a mile thick in places, Clarke said that is why the “numbers look astronomical,” but he thinks what eventually unlocks its vast potential will be some little guy who hits it big.

“A lot of big companies don’t do riskier things, but they let the little guys do it and even if nine of them fail, if one hits it, the big guys can come in and buy him out,” he said. “That’s very common in the oil industry. The real oil finders often are the little guys who go out and take the risk.”

California’s nonpolitical side of the Monterey Shale, as in oil and natural gas, generally, can be found in the state Department of Conservation’s Division of Oil, Gas and Geothermal Resources (DOGGR), which is in the middle of a multi-year process to develop new rules for hydraulic fracturing and which generally oversees oil/gas operations on a nonpartisan basis.

After firing two top-ranked officials and appointing new people, Gov. Jerry Brown has talked more bullishly about the state’s hydrocarbon riches amidst an aggressive statewide policy pushing more renewable energy reliance. Brown in March voiced strong support for the DOGGR fracking rules effort. Industry organizations are applauding Brown’s apparent new open-mindedness.

While leading the charge on climate change, the governor in his second term “recognizes that petroleum energy is going to be the foundation for the state’s energy economy for a very long time,” a veteran industry association official said.

While DOGGR officials avoid making public statements about the Monterey potential, their boss and Brown appointee, Jason Marshall, the conservation department’s chief deputy director, has said the Monterey “could” be a boon to the state’s economy, but he qualified it by putting heavy emphasis on “could.” Oil prices exceeding $90/bbl may be a greater incentive for the Monterey, but Marshall reminds anyone who will listen that producers never get every barrel of potential oil out of a formation “and that’s especially true in this [the Monterey] geologic formation.”

Third-party state geologists and engineers see the Monterey as “the source rock” for what are clearly significant amounts of oil produced from already existing fields, primarily in Kern and Ventura counties, north and west of the Los Angeles Basin. Overall, the Monterey could indeed include 15 billion bbl, the state professionals agree.

From a basic geology standpoint, Marshall acknowledged there already have been some efforts to use fracking to produce oil directly from the Monterey, “but apparently none of the companies that have tried it so far have had significant success, and it doesn’t appear to be widespread. Unlike other shale formations, such as the Bakken, the Monterey Shale already has been highly fractured by natural forces, making the hydrocarbon reserves disjointed and less predictable.”

That is why Marshall agrees with others such as Clarke who says it will probably take advancement in technology or methodology to unlock the oil production potential.

For now, Marshall and DOGGR may view the Monterey Shale prospects as intriguing, particularly because of the potential economic benefits underscored in the recent USC study, which had funding from the Western States Petroleum Association (WSPA) and a Los Angeles-based nonprofit think tank, The Communications Institute. However, the state agency’s main focus is “resource protection,” which includes the draft fracking rules that generally have some support from WSPA, although the industry association has its disagreements, too.

Unlike individual E&P companies, service providers and the geologic engineering analysts, WSPA is not reluctant in the least to talk about the Monterey, although its individual members have widely varying views, according to Tupper Hull, a vice president for the organization.

Hull thinks part of the ambivalence in California toward the Monterey stems from the state’s history of what he called “tense battles” between coastal-based environmentalists and the state’s sprawling economic and agricultural breadbasket in the great central valley, over which a good portion of the Monterey is found.

The situation is made more complex by the ongoing debate surrounding hydraulic fracturing. Hull said it attracts all of California’s normal elements for controversy – politics, regulation, money, land use and environmental fears.

“Some of our members say they don’t think Monterey is going to be a big part of their business plans,” Hull said. “Others have a very different view, so it is matter of whether (a) the oil is there. Plenty agree it’s there, and (b) no one really disputes that there is a whole lot of it.” (The EIA’s 15.5 billion bbl estimate seems to have consensus around some parts of WSPA.)

One of WSPA’s major members, San Ramon, CA-based Chevron Corp. officially looks at the Monterey this way:

“[We have] a large position of more than 200,000 acres in the San Joaquin Valley. In 2012, it had net daily oil production there of 162,000 bbl/d, of that 30,000 bbl/d were from the Monterey formation,” a spokesperson said. “We’re assessing future opportunities in the Monterey; however, they will have to compete for capital with other opportunities around the world.”

On May 29 following Chevron’s annual shareholders meeting CEO John Watson also had some comments about Monterey Shale prospects that were in line with the company’s conservative outlook about whether it will prove profitable for an operator such as Chevron. ”I think the jury’s out a little bit on the Monterey Shale. … I don’t think we’ve completed — the industry has completed — the assessment enough to reach a conclusion. Others have been very bullish and have spoken out on this…We haven’t seen the same economics that others have up to now.”

Chevron’s caution reflects much of what geologist Clarke told the AAPG organization newsletter, which included acknowledgement the Monterey could hold twice as much recoverable shale oil as the Bakken and Eagle Ford plays combined. That being that there have not been any fully successful Monterey plays, and some speculation is that the Southern California part of the Monterey is too “tectonically faulted and fragmented” for horizontal drilling to be effective.

Geologist Clarke, however, did not agree with this pessimism necessarily. The Monterey does not lend itself to homogeneous conclusions about its geological makeup across the entire play. That makes it tough for prospective E&P operators to deal with government regulations and development; they simply don’t have enough good data.

For Clarke, the Monterey doesn’t lack potential; it lacks solid information on specifically focused areas. The question is when, or if, someone will come forward to make the financial and technological commitments to take some of the geologic mystery out of the equation. In 2013, there is no clear answer to that question.

On May 30, state lawmakers rejected a bill that would have stopped drillers from using hydraulic fracturing to free oil and natural gas from shale beds until state regulators implement rules for the controversial practice.

Richard Nemec is the West Coast correspondent for P&GJ. He can be reached at rnemec@ca.rr.com.

Comments