October 2019, Vol. 246, No. 10

Northeast Energy

Price Spikes in New England Limited by Natural Gas

It seems like each winter we see consumers in New England suffering not just from freezing temperatures but also the highest energy prices in the country – largely because there’s not enough natural gas infrastructure to serve the region during periods of peak winter demand. This past winter, the news was a little bit better.

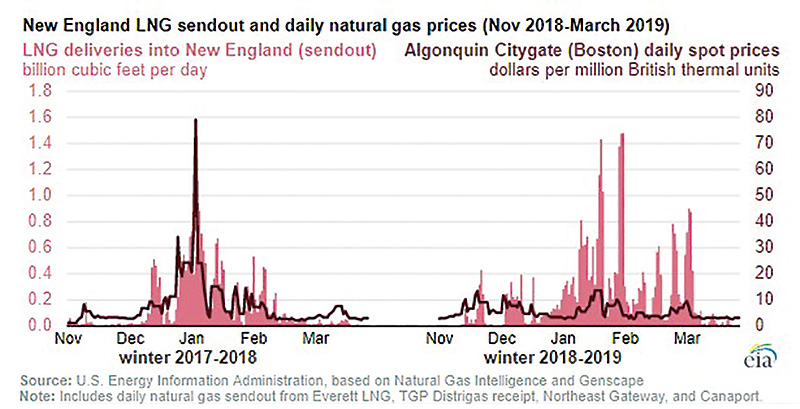

Natural gas prices generally follow seasonal patterns and tend to rise in the winter. For example, the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) has suggested that liquefied natural gas (LNG) imports helped to moderate energy price spikes in the region this year. EIA’s charts below compare LNG deliveries to New England and daily regional spot prices for the winters of 2017-2018 and 2018-2019:

The winter seasons were similarly cold in both years, according to EIA data (though EIA also notes that cold weather events were more episodic last winter than the sustained cold of the previous winter). But the LNG deliveries into New England rose, partly because global LNG markets have recently had excess cargoes available at prices below those of last year.

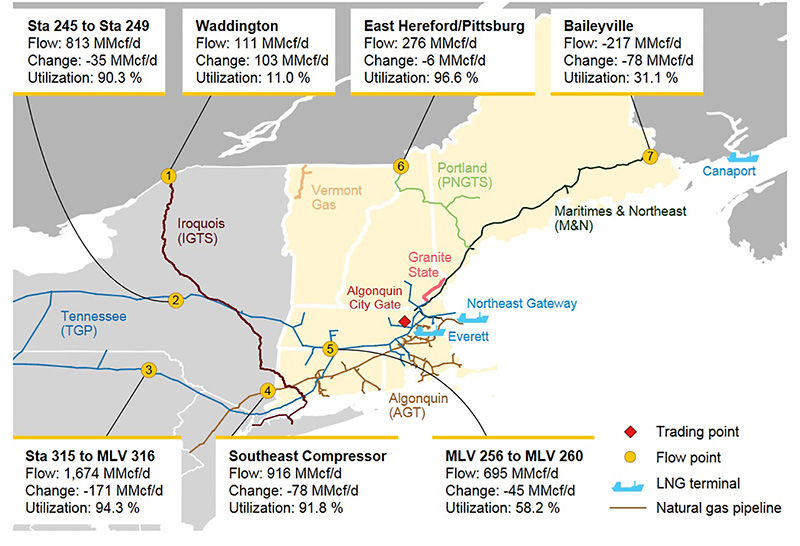

Still, domestic infrastructure constraints in New York and New England mean that residents remain faced with relatively high and uncertain energy prices plus the possibility of winter shortages – not to mention the unnecessary stress those conditions put on the region’s power grid.

It doesn’t have to be that way. New England is in close proximity to two of the largest natural gas reserves in the world – the Marcellus and Utica shale formations – stretching from Ohio into West Virginia, Pennsylvania and New York. These could easily supply New England with affordable domestic natural gas, just as they already supply huge swaths of the Mid-Atlantic and Midwest regions in the United States.

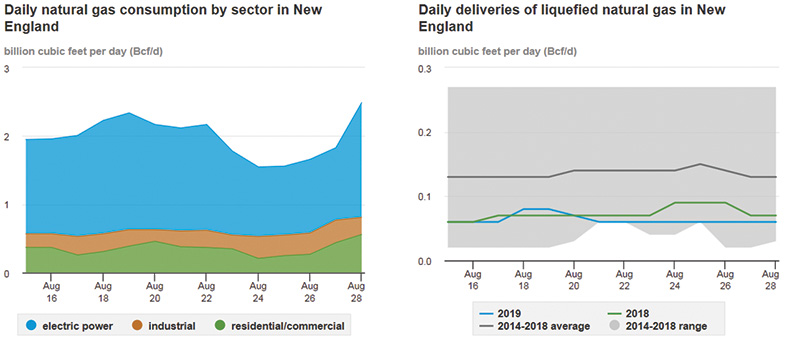

Instead, the New England region remains uniquely dependent on LNG imports. Consider that a whopping 90% of the $1.2 billion in LNG imported since 2016 has gone to New England and nearby New York.

This outcome is especially ironic given that other regions in the U.S. – especially the Gulf Coast – have such an abundance of natural gas that they’re rapidly shifting to exporting LNG in huge quantities. In fact, by the end of 2019, the U.S. will become the world’s third-largest LNG exporter. Yet all the while, LNG cargoes from Trinidad and even Russia, continue to flow into New England.

The associated cost is considerable. API Chief Economist Dean Foreman recently calculated that the region’s consumers paid about $670 million more for the imported LNG than they would have paid for domestic natural gas – which would be easily accessible with sufficient pipeline infrastructure to deliver it.

Instead of leveraging domestic natural gas from nearby states, New England has relied on imported LNG at prices that have been more than 60% higher and more than twice as volatile. The chart shows just how steady the average price for domestic natural gas (Henry Hub) has been, compared to the average landed price of imported LNG. Looking forward, EIA’s 2019 Annual Energy Outlook projects U.S. natural gas prices will remain consistently low. Global LNG prices on the other hand, are highly uncertain and will depend on many factors far beyond the U.S.

Thus, importing LNG to help New England meet its energy needs could continue to result in high natural gas prices throughout the region. Yet, this unfortunate outcome could be easily avoided by adding pipeline capacity. P&GJ

Author: Jessica Lutz is a writer for the American Petroleum Institute and a graduate of the University of Michigan with degrees in communications and political science.

Comments