September 2018, Vol. 245, No. 9

Features

Permian, We Have a Gas Problem

By Jamie Brick, McKinsey Energy Insights

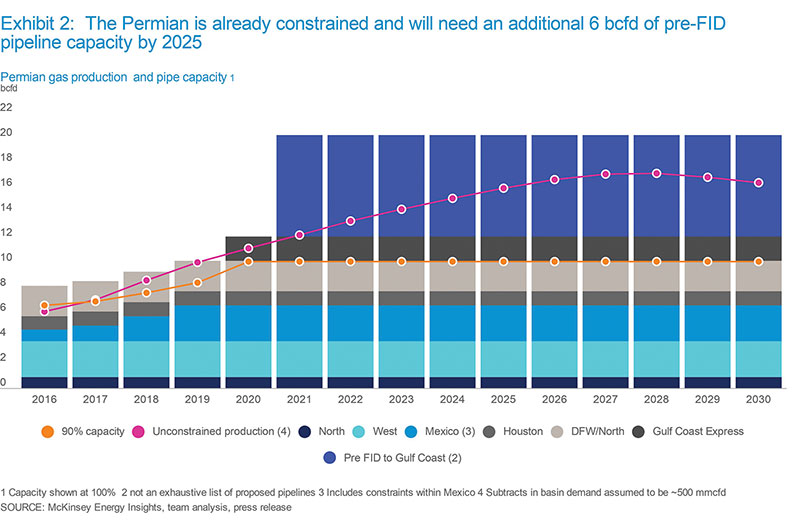

Permian gas prices will remain weak for the next few years despite nearly 2 Bcf/d of additional pipeline capacity coming online by 2020. This is because the Permian, predominantly a shale oil play, has large quantities of associated gas production.

McKinsey Energy Insights expects Permian crude and NGL production to grow from 3.3 MMbpd in 2017 to 8.8 MMbpd by 2025, which in turn should cause natural gas production to rise from 7.1 to 16 Bcf/d over the same time frame.

The Texas Gulf Coast and, to a lesser extent, Mexico are the most likely destinations for incremental Permian gas volumes. While the fundamentals support additional pipelines (among those, the large quantities of new gas being produced), there is a real risk that the Permian will become over-piped in the medium to long term.

As private equity looks to fund the next major pipeline project, it will be increasingly drawn to projects linking the Permian to the demand centers in the U.S. Gulf Coast. This is because pipelines typically offer stable revenue, and the regulatory risk is minimal in an oil and gas-friendly state like Texas. Combining favorable fundamentals, minimal regulatory risk, and private equity, there is a real risk that too much capacity will be developed in the long term.

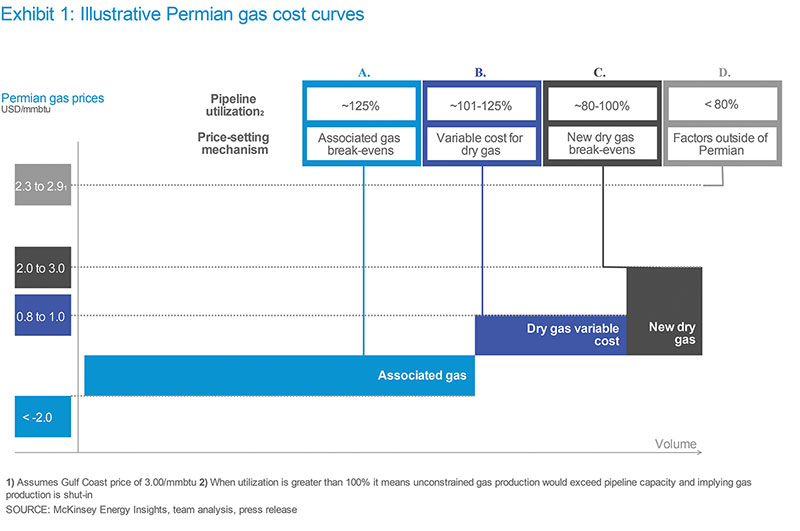

Unconventional Economics

If pipeline utilization exiting the Permian remains below 80%, in-basin gas prices are expected to be about $0.10/MMBtu cheaper than on the Texas Gulf Coast, because of the variable cost of transporting the gas (Exhibit 1D). Once pipeline use exceeds 80%, in-basin prices start to decrease as Permian gas competes with other gas for access to this limited pipeline capacity, causing in-basin prices fall further (Exhibit 1D). The Permian has already crossed that 80% threshold, and prices are starting to show the effects.

This scenario would usually result in operators reducing drilling for gas, but only approximately a quarter of Permian gas production is not associated with oil and is sensitive to in-basin gas prices. If in-basin gas prices fall, the first to be affected will be the <5% of production that comes from new gas wells, which have a breakeven of between ~ $2-3/MMBtu (Exhibit 2C). Next would be the ~25% of Permian production from gas wells that have already been drilled, which break even at about $0.80-1.00/MMBtu (Exhibit 2B).

The remaining ~75% of gas production is associated with oil, and can even have a negative value, as oil revenue is what drives investment decisions for those wells (Exhibit 1, A). Since this associated gas is largely unaffected by in-basin gas prices, we can expect to see Permian gas production continue to increase even as the takeaway capacity approaches 100%.

Where will incremental Permian gas production go? There are two primary destinations for incremental Permian gas: Mexico and the Gulf Coast. Once bottlenecks are resolved, new pipelines to Mexico should add an effective export capacity of about ~2.9 Bcf/d, a much-needed outlet until new pipelines to the Gulf Coast come online from 2020 (Exhibit 2).

However, both routes face problems. Building additional pipeline to the west is difficult, especially in California, while western gas demand is uncertain due to higher solar generation. Meanwhile, competing volumes from the Marcellus and SCOOP/STACK, as well as higher pipeline development costs for long-distance interstate pipelines, makes building a pipeline to the north less attractive.

Too much of a good thing? In other areas, we have seen anecdotal evidence indicating private equity money competes against itself, causing the required returns to fall. Additionally, Appalachia provides a good example of how excess pipeline can develop in response to wide basis differentials. (McKinsey Energy Insights models indicate there is more pipeline capacity exiting Appalachia than production until after 2026.)

Most of the proposed new pipelines linking the Permian to the Gulf Coast would be regulated as an intrastate pipeline and are generally easier to permit and build compared to interstate, or even northeastern interstate pipelines.

As a result, it is more likely in the long term that excess new pipeline capacity will be built from the Permian to the Gulf Coast rather than too little.

LNG Demand

Assuming there is sufficient pipeline capacity, high oil prices may not depress prices in the Permian as much as expected. This is because a $10 per barrel increase in oil price leads to an increase of about $1.20 MMBtu in oil-linked LNG (assuming a 12% slope), with no direct impact on Henry Hub-linked U.S. LNG prices.

From 2020 to 2024, we expect about 2 Bcf/d of surplus capacity at U.S. LNG export terminals. If oil prices were to increase due to, for example, a decrease in Venezuelan crude oil production or some other unforeseen shock, then oil-linked LNG contracts would become more expensive. Demand for U.S. LNG would become more price competitive and provide an outlet for additional associated Permian gas.

Conclusion

The Permian is in a unique position. High oil prices lead to additional gas production and put downward prices on in-basin gas prices. The Permian’s gas problem can be divided into two phases.

The first phase is from now until about 2020 where there is insufficient pipeline capacity and in-basin prices are low. Despite building nearly 2 Bcf/d of additional pipeline capacity by 2020, additional capacity is needed. This leads to the second phase. Market fundamentals may attract too many pipelines, and the Permian is at risk of becoming over piped. P&GJ

Comments