August 2014, Vol. 241, No. 8

Features

Pipeline Fever In Mexico

Both Pemex and CFE are promoting new pipeline projects at a fast pace in advance of the most significant energy reform in Mexico in a half-century. The projects are to follow the old rules of government procurement: these state-owned enterprises (SEO) offer the credit rating of the Mexican government to serve as a bankable, long-term service agreement.

The criterion for awards is the lowest price for energy. The contractor lays the pipeline at his expense and is also responsible for obtaining rights-of-way. Pemex is promoting transisthmian pipelines that would help it develop Asian markets. CFE has already awarded pipeline routes along the western mainland and is promoting five new natural gas lines to feed its power generation needs in northern markets.

This article provides an overview of the CFE projects as well as a critique of the current gas market structure in which CFE and Pemex operate.

CFE Gas Pipeline Roadshow

On April 23, at the elegant venue of The Houstonian, the first iteration of the pipeline roadshow of Mexico’s Federal Power Utility (CFE) took place with a presentation by Guillermo Turrent, who, since February 2013, has been CFE’s director of modernization. Turrent returned to Mexico after many years in the United States where he worked in natural gas and power markets, having been employed by Sempra, Shell and EDF, among others, in trading and business development.

The event was sponsored by the Greater Houston Partnership and the Mexican Consulate. There were about 200 attendees, many of whom had flown in from Mexico, as this was the first roadshow that CFE had offered for its new group of pipelines. Among those in attendance was Fernando Luna, director of PMI’s office in Houston.

Turrent argued forcefully that it was unacceptable for CFE to be paying $20/MMbtu for LNG in Manzanillo while gas was available for $4 in Texas. It was time to play catch-up in pipeline deliverability fast. He alluded to one of the promises the administration had made, namely to reduce the prices of energy.

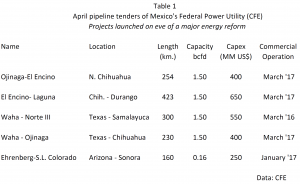

Taken together, the five pipelines would increase gas deliverability by upward of 6 Bcf/d, with a combined capex of $2.2 billion. Commercial operation was expected to begin in less than a year for the line from Waha, TX to Samalayuca, Chihuahua; the other four lines are expected to be operational by the first quarter of 2017 (Table 1).

Two of the five projects start in the United States, but Turrent explained that CFE would not specify the precise route of the pipelines, as the developer would be responsible for obtaining rights-of-way (map). He said CFE would seek ways to “lower the risk” for the developer regarding rights-of-way. He also mentioned that in cases where a gas pipeline could serve a local community or industry CFE would make recommendations to the developer.

Turrent was optimistic that, in time, a system of electronic bulletin boards could be established by which customers could post the availability of both supply and capacity, thus creating a secondary market and avoiding penalties for being long or short.

The use of such bulletin boards would bring about the end of two decades of market distortion: since 1995, there has not been an internal price hub for natural gas in Mexico; all natural gas is netbacked from Henry Hub, following formulas established by Mexico’s Energy Regulatory Commission (CRE).

Q&A At The Houstonian

The question-answer period lasted for most of an hour. One attendee wanted to know why the rush? Why not wait until the 2014 Energy Reform legislation is approved so the CFE and pipeline developers can reset their expectations accordingly?

The speaker replied that CFE had developed 20 pipeline projects and was moving forward with only the five presented.

“With or without the energy reform, we need this additional gas deliverability as soon as possible,” he said. “When the reform is finalized, then plans for the other pipeline projects could change.”

One attendee asked if a developer could build a pipeline with greater capacity than the tender specified. If so, would the developer have full commercial rights to market the gas? Turrent said the developer was free to add capacity, but that CFE would have the right of first refusal in any particular commercial transaction.

Another question concerned whether CFE intended to compete with Pemex Gas (PGPB). Turrent replied CFE did not intend to go after Pemex’s gas customer list, but added the proposed independent system operator for gas pipelines, Cenagas, would only have jurisdiction over the national gas pipeline grid that is operated by Pemex.

The commercial relationships with other pipeline systems, such as those found in central Mexico in the Bajío region, would be worked out in separate interconnection agreements.

Who Owns The Border?

With the exception of the Altamira LNG terminal and supplies by CFE and Sempra in Baja California, all natural gas imports into Mexico have been controlled by PGPB. Even the 2013 LNG cargos into Manzanillo were arranged by PGPB. Mexico’s Natural Gas Act of 1995 was supposed to encourage new gas transportation pipelines that would compete with Pemex. Almost two decades later, there are exactly zero such pipelines. It is the same story for natural gas storage.

What does the future hold? There are signals both positive and otherwise. CFE intends to have its gas supply agreements currently held by PGPB transferred to its own accounts. At the same time, PGPB, through offshore subsidiaries MGI and TAG, is planning for gas pipeline projects in the United States and Mexico.

Critics of the status quo call for PGPB to be restricted to marketing the gas produced by Pemex itself, with no future role in managing or controlling gas imports, which should be left open to private gas marketers. The important detail is that the primary market for natural gas in Mexico, where CFE is the largest customer, should not be under monopolistic or duopolistic control by SEOs.

An Alternative To SEO-Centric Financing?

At the CFE road show, the speaker reviewed the several projects. Commenting on CFE as a creditworthy company, he observed its credit rating is that of the Mexican government: Moody’s (Baa1), S&P and Fitch (BBB). Stated differently, CFE’s credit-worthiness cannot be separated from that of the Federal Government of Mexico.

In the market redesign for the energy sector to be enacted into law there may be ways to create alternatives to either Pemex or CFE as the anchor customer for new pipeline projects. The reality, though, is that the federal government is the one backstopping the contracts at the moment; it is a polite, commercial fiction that there are separate, state-owned companies carrying out business as usual.

Another imaginable possibility would be for the federal government to establish a trust fund that would be the bankable customer, with Pemex or CFE as two of many capacity-holders on the lines.

Conclusions

The CFE’s argument for rushing ahead with pipeline tenders that would be dated April 2014 – the very month that the energy reform was expected to be finalized – is not convincing. What difference would it make if those same tenders were dated July 2014, after the reform legislation had been enacted?

With that reservation, the outlook for the development of a gas market in Mexico – with a true gas hub inside Mexico – is promising under Turrent’s leadership and the moral and regulatory support of CRE.

The pipeline aspirations of Pemex Gas on the other hand is more a topic for concern than rejoicing – that is, for gas market advocates, of which there are too few in Mexico.

Author: George Baker is publisher of Mexico Energy Intelligence, a Houston-based newsletter. He also publishes Energia.com, a venue for interviews, calendar events and public-interest reports.

Comments